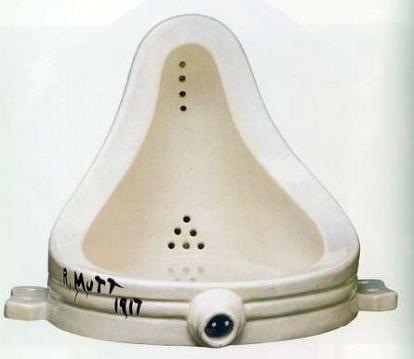

Some worship his genius; others believe that because of him the history of art swerved badly off course. One thing is for sure: the legacy of Marcel Duchamp – the man who put urinals and bicycle wheels into galleries and called them art – has been the most dominant single influence over the art of the late 20th and early 21st century, far outstripping even that modern master, Picasso.

It is this legacy that the Barbican Centre in London will celebrate in Dancing Around Duchamp, a season running from February to June next year spanning art, dance, music, theatre and film. At its centre will be an exhibition that examines Duchamp’s effect on the work of four men: composer John Cage, choreographer Merce Cunningham, and artists Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

Cage was the first of the four to meet Duchamp, in New York during the second world war, but through the 1950s and until Duchamp’s death in 1968 all were directly influenced by him: according to Barbican senior curator Jane Alison, he provided the younger artists with an avant garde, Dadaesque model of art that was a “counter to the tired, macho abstract expressionism” then in the ascendant in New York.

Instead, Duchamp’s art was ideas-filled, gender-bending, punning, chance-reliant, playful, sometimes absurdist. As Cage said: “I can’t get along without Duchamp. I literally believe Duchamp made it possible for us to live as we do.” For Johns, Duchamp “changed the condition of being here”.

It was at least partly through the conduit of these four men, each hugely influential in his own art form, that, according to Alison, Duchamp came to “drastically alter the art of the 20th century. He is the father of conceptual art and possibly the entire of contemporary art, as well as pop art and postmodernism.”

The exhibition will be staged on the centenary of the scandalous exhibition of Duchamp’s painting Nude Descending a Staircase at the Armory, New York – the event now regarded as marking the introduction of modern art to the US. (The painting was trenchantly denounced, to Duchamp’s delight, with one US paper renaming it Explosion in a Shingle Factory.)

The Barbican will show that work, on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, along with a version of one of Duchamp’s most significant sculptures, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, commonly known as the Large Glass, which consists of enigmatic images created from wire, dust, foil and other materials, sandwiched between two glass panels – the upper suggesting the bride, the lower her bachelors. The Barbican will borrow the replica, sanctioned by Duchamp, that is owned by the Moderna Museet, in Stockholm, since the original, in Philadelphia, is too fragile to travel.

The Large Glass was a work of enormous significance to Cunningham, whose 1968 dance work, Walkaround Time, was a direct homage to Duchamp, and whose set, created by Johns, consisted of versions of the Large Glass. Cunningham described how the man, as much as the art, influenced him. “The main thing, I think, is the tempo. Marcel always gave one the sense of a human being who is ever calm, a person with an extraordinary sense of calmness, as though days could go by …”

Walkaround Time also used the dance equivalent of Duchamp’s readymades, in the form of standardised warm-up exercises used by Cunningham’s dancers; and the early performances featured Cunningham himself changing his clothes while in motion, as his cross-gender homage to Nude Descending a Staircase. The exhibition will feature Johns’ original set for the piece.

A further theme in the exhibition will be chess – a game that obsessed Duchamp and at which he was hugely skilled; he published, with chess theorist Vitaly Halberstadt, a treatise on problems of the chess endgame. Cage visited Duchamp for chess lessons: he would usually be set to play with Duchamp’s wife, Teeny, also a skilled exponent of the game.

He recalled: “Marcel would glance at our game every now and then, and in between take a nap. He would say how stupid we both were.” One of Cage’s works, Reunion, featured him playing chess onstage with Duchamp on a wired-up board; certain moves would automatically trigger certain electronic sounds, or would be translated into images on television screens.

During the exhibition’s run the Barbican will stage performances of works by Cage and Cunningham in the gallery on Thursday evenings and at the weekends; but even at other times the show promises to be a lively experience. Designed by artist Philippe Parreno (who co-authored the film Zidane: A 21st-century Portrait with Douglas Gordon), the exhibition will be accompanied by soundscapes, and music from a remote-controlled grand piano.

Duchamp’s connections with the theatre will be brought in, too: Cheek By Jowl will perform the absurdist play Ubu Roi, by Alfred Jarry, a key precursor to Duchamp’s work; and an adaptation of Watt, the novel by another of Duchamp’s chess opponents, Samuel Beckett, will be performed by Barry McGovern. Duchamp and Beckett were friends during the war, and it was Mary Reynolds, Duchamp’s companion, who helped Beckett find a haven outside Paris in the summer of 1940; during those the long dull days in Arcachon, on the Atlantic coast, the two men would wile away the time with chess games in a seaside cafe. Duchamp always won.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.