Weird beings … Thomas Schutte’s United Enemies 2011 at the Serpentine Gallery in London. Photograph: Martin Godwin for the Guardian

Lovers and children, men and monsters and the artist himself appear in Thomas Schütte’s new exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in London. Here he is, a young student in 1975, long-haired, pensive, eyes downcast behind his aviator glasses. One of 20 self-portraits he painted while a student of Gerhard Richter, Schütte reworked the same photographic image, gridding it up and rehearsing his own face wearing the same expression, over the course of a summer month.

A sort of memento of lost time, the youthful portrait shares a room with a sunken-cheeked, heavy-browed and bearded old man. This fanciful 2011 bronze head on its tilted plinth, titled Memorial for Unknown Artist, might also be a kind of self-portrait, throwing up his hands in warning or exasperation at his younger self. Who is this old, patinated green geezer: an ancient god, a projection of the artist in an imagined old age? The raised forearms and hands, smooth as rubber gloves, measure the void. He is almost funny, like Bill Nighy’s squid-faced captain in Pirates of the Caribbean. Almost, but not quite.

Schütte’s show is full of such uncomfortable surprises and dualities, different registers of touch and feeling. This is to be expected of an artist whose output is enormously varied. Ranging from architectural models and actual buildings, to diaristic watercolours, observational drawings and sculptures, Schütte’s variety could be bewildering, and larger exhibitions often attempt to present an overview. The Serpentine, and a concurrent, related exhibition at London’s Frith Street Gallery, focus almost entirely on human presence: heads, figures and the artist himself.

Even with this focus, Schütte’s work is full of invention. A whole room is devoted to imaginary bronze heads, each on a little shelf. Think of Honoré Daumier’s caricatures, Picasso, Franz Xaver Messerschmidt: Schütte riffs on both art and on the lump, on material and meaning. These heads are called Wichte, or Jerks, and they’re just the kinds of jerks you might avoid in a bar. “Hair, feet, hands, they’re a nightmare!” Schütte joked to me last week, though I don’t think he was really joking.

Look more closely and you see that Schütte is also riffing on basic problems and opportunities: how to form noses, or eyes in their sockets, eyebrows, ears, hair, character and expression. He has no set method, approaching each anew.

One head appears to be sleeping. She glows with a strangely indeterminate colour: layers of lacquer have been applied to the aluminium cast by the specialists who pimp up motorcycle fairings and tanks with layers of sprayed colour, giving this smooth, tender face and her crunchy impasto hair an otherworldly quality. She seems to come from the future. In fact, she is Walser’s Wife, an imagined portrait of the wife of the great German-Swiss writer of “micro-fictions” Robert Walser.

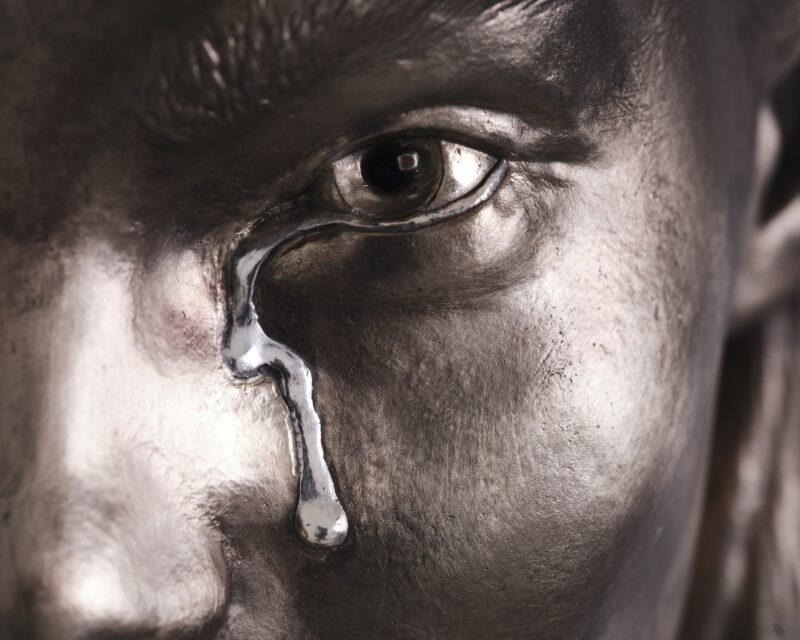

Schütte’s works, too, might be seen as micro-fictions – moments rather than stories, each from a different sculpted or drawn world. Another head sleeps, resting on her cheek, a little lumpen tear bulging beneath her eye. Look at the braidedness of her bronze hair, the malleable directness of the sculpted flower in her hair. There is an idea of beauty here, and beauty in art is immeasurably difficult. This sculpture could be kitsch, but isn’t. Somehow, Schütte manages to undermine the form, giving it a twist. I stand there and think, how dare he?

Then there come monsters and weird beings. Surrounded by black-and-white photographs of babyish, malevolent, ghostly heads, from a series of small Fimo sculptures the artist made in the 1990s, stands Father State or Vater Staat, a looming, rust-coloured, almost four-metre tall and deliberately inexpressive figure in a voluminous robe and hat. An implacable patriarch, he is like a figure from an undiscovered civilisation, or an unbending father from a scary puppet theatre, commanding the Serpentine’s central gallery with an iron (or in this case steel) will.

The contrast with Schütte’s rows of drawings and watercolours could not be greater, but again we see a whole gamut of approaches, though his drawings and prints are invariably more personal. For a long time, Schütte has drawn himself, using a mirror, or simply working over his own reflection on an etching plate with a drypoint needle; he has followed David Hockney (and Ingres) in his use of a camera lucida, a drawing device that projects a reflected image on to a surface. Here he is again and again, staring into a little round glass as though through a porthole, unsmiling and focused, somehow other than himself. Other sitters come and go: an ex-girlfriend, his daughter, his son nodding off in a chair. There is a great deal of tenderness. The strokes are sometimes delicate and precise, sometimes looser.

The inverted reflection in Schütte’s camera lucida is only ever a starting point, and often he doesn’t use it at all. A terrific draughtsman, he is an inventor rather than a copyist. There are faint, perspicacious pencil lines, quick swipes of fatty black ink, lively, confident portraits, bright washes and stuff erupting from the paper that makes you want to back off a pace or two: a toothy Halloween head, a faded swan that turns into Hitler (replete with snaggly little swastika), bleak drawings from the artist’s debilitating bouts of depression, funny images that seem to be drawn in code.

Over at Frith Street Gallery, there is a series of drawings of flowers, wan little images of limp decay. There’s almost nothing to them, but they make my stomach drop. And here, too, are some of the most extreme sculptures I have seen by the artist, huge men with staves, based on small sculptures (so small, the men wear bottle-caps for hats), but computer-scanned, enlarged and cut from laminated wood, stained brown. For all the directness of his drawing, Schütte employs highly sophisticated techniques to enlarge his sculptures. Outside the Serpentine stand a pair of his United Enemies – originally small modelling clay, cloth and bamboo sculptures that sat under bell jars, now battling bronzes, pairs of bound-together figures that rear over us, roped together in conflict.

Just blowing things up doesn’t make them better. Schütte knows this. As a ceramicist, he also knows how to use the accidents of glazes, and how sculptures can slump or break in the kiln. The question is, how to take advantage of such accidents. This is true even in drawing – a slip of the pen, a line that careers off on its own unwilled way. Such unpremeditated things are often where the art is. “You don’t make art,” Schütte observed when we spoke last week. “You find it.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.