Tate Modern has opened a new Rothko Room as part of its rehung permanent galleries. Actually, Rothko Room seems like an overblown title. The space reserved for Mark Rothko‘s mural-sized masterpieces in the new Transformed Visions suite, which explores abstract art and its influences, is the least ostentatious and feels like the smallest the museum has ever set aside for them. It is not closed off, so the soundtrack from a nearby video installation intrudes. In this modest display, not all the paintings are even included. It’s hard to imagine why anyone would choose not to display one of Rothko’s mighty revelations.

In 1959, the New York painter withdrew from the biggest commission of his life so far, to decorate the new Four Seasons restaurant in Manhattan. This high-class dining establishment – which is still in business – can be found in the Seagram Building, a beautifully restrained classical skyscraper designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. At the end of the 50s, this was Manhattan’s newest and most glamorous skyscraper. Rothko, a bold abstract painter whose rectangles of hovering blue and lemon, brown and orange already hung in a good few Upper East Side apartments, seemed the natural choice to provide it with art at once avant garde and, in its colours, luxurious.

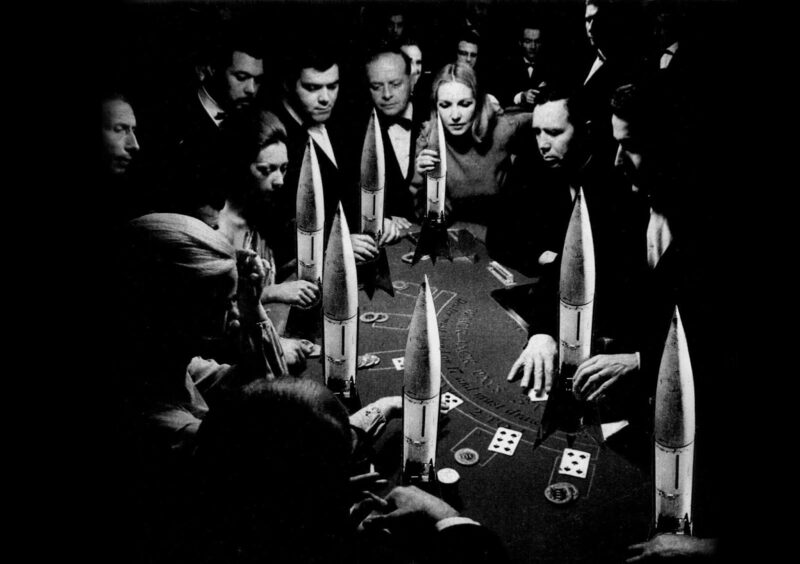

Rothko painted canvases for the restaurant that he called “murals”. He was fascinated by the idea of “creating a place”, shaping an experience of space through art. He visited Italy while he was planning his Seagram murals, and they show the direct influence of the places he visited there: Rothko’s paintings use curious frame-like devices that echo Michelangelo’s dead windows in the Laurentian Library Vestibule. Meanwhile, the deep reds and purples of his canvases recall the frescoes of Pompeii.

He worked passionately at these paintings – and then in 1959, suddenly decided that a restaurant was not the place for them. Rothko eventually donated the best of them to the Tate, largely it seems to snub American museums, but also because he loved JMW Turner. Hence the Rothko Room.

They are works that creep up on you like rolling thunder. In this latest incarnation at Tate Modern, a bit of colour catches your eye, a hovering rectangular frame, a smoky door in the purple void. At first, it all may seem just pretty. But soon, the dark bloody palette and majestic architectural qualities begin to lock you into their world of foreboding. They are abstract paintings that have the precision of pictures – but what is Rothko picturing? It seems like a message from the end of the world.

Whenever I see these paintings, they make me think of some timeless masterpiece. Recently I have been looking at Rembrandt’s Belshazzar’s Feast, in London’s National Gallery, with its perversely luscious depiction of a tyrant horrified by the supernatural appearance of God’s words on a wall during a banquet, prophesying his fall. Rothko’s paintings look to me now like the Writing on the Wall.

Make a fuss of them, don’t make a fuss of them, show them in a reverent chapel-like space or stuff them in a corner room with a video soundtrack muttering into it – no matter. So long as Tate Modern displays these paintings, they will blaze bright and dark as masterpieces that shudder the world.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.