In the past, the Rencontres d’Arles photography festival has worked best when it has been steered by a high-profile guest curator. In 2004 Martin Parr’s wide-ranging and democratic vision underpinned a programme that was both mischievous and thought-provoking, while in 2009 Nan Goldin created a series of shows, talks and late-night screenings that reflected her hard-hitting, confessional style. This year, though, there is no unifying vision, and the festival’s subtitle, “A French School”, might have made more sense had it been a question rather than a statement.

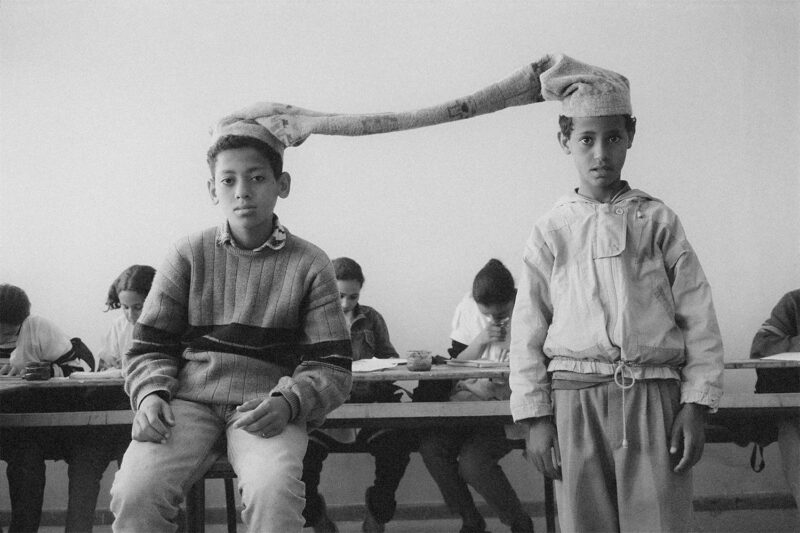

In the centre of town, the biggest and most well-attended show is a historical one: Gypsies by Josef Koudelka. The book of the same name, first published in France in 1975 by Robert Delpire, is one of the defining photobooks of the 20th century, and was reissued last year in an expanded edition with more than 30 previously unseen images. Koudelka’s singular brand of poetic sadness is, if anything, more powerful today given that the world he photographed has all but vanished in the intervening years.

Many of these austerely evocative black-and-white photographs retain their power to astonish, none more so than the haunting image of a beautiful, bewildered young man in handcuffs. He stands in the foreground as if mesmerised by Koudelka’s camera while, behind him, a string of onlookers and a pair of uncertain policemen wait for this mysterious drama – the young man has just been arrested for murdering his wife – to unfold. The exhibition is augmented by letters, layouts and original editions of the book, all of which provide a glimpse of the restless imagination behind this now seminal body of work.

Down by the river in one of Arles’s beautiful churches, Sophie Calle is showing two new interrelated series, both set in Istanbul. They address one of her abiding themes: absence. The Last Image comprises a series of portraits of blind people, most of whom lost their sight suddenly. The photographs are accompanied by concise but moving texts in which her subjects describe the last thing they saw. In another room is Voir la mer, Calle’s film of a group of people seeing the sea for the first time. As always, her work operates in that territory between the natural and the choreographed, and the show has a cumulative melancholy power. I saw one person leave the church in tears.

Across town in the disused railway sheds that yearly become exhibition spaces was the work of the 15 nominated artists in contention for the festival’s Discovery award. It was a mixed bag. The most realised work by far belonged to the American Lucas Foglia, a young graduate from Yale. Entitled A Natural Order, the series looked at people who, for various reasons – religious beliefs, environmental concerns, apocalyptic visions – have retreated from society to live, as Foglia puts it, “off the grid”. Foglia specialises in a kind of gentle yet incisive documentary approach in which he befriends and spends time with his subjects, then photographs them when they are totally at ease in his presence. In one arresting image, a naked child perches on her father’s chest as he floats, eyes closed, in a lake. In another, three serene, long-haired teenage girls wade in a river, fully clothed.

The vision is often edenic, but in Foglia’s photographs all is not what it seems. A young man sits in his room in a camouflage jacket, an assault rifle lying on a table in the background. A decomposing bear lies in a clearing like some nightmarish vision of nature’s deepest, darkest forces. Mennonites turn out to be ex-Hells Angels; a once-virgin woodland has been turned into a car park; utopian dreamers fleeing the digital overload converse on laptops and cellphones. This is formally beautiful, thought-provoking work from an already assured talent.

I also liked Nelli Palomäki‘s intimate black-and-white portraits which manage to look both old-fashioned and somehow new. They exude a powerful stillness that used to be common in photographic portraiture but is rare in the digital age.

Perhaps the most surprising work, though, belonged to Nadège Mériau, a Tunisian-born photographer living in London. Her visionary landscapes resemble the apocalyptic paintings of John Martin or those disturbingly viscous medical images taken by tiny cameras inserted into the body. They are actually extreme close-ups of the inside of bread, taken on a large-format camera: a kind of worm’s-eye view of buns, rolls and loaves. Mériau also photographs the inside of vegetables and milk with the same surreal sci-fi results. Her “intra-uterine architectures”, as she calls them, are utterly singular and a little bit bonkers, but they captivate all the same.

Regine Petersen also intrigued with her strange visual narrative, Find a Falling Star, about meteorites and their impact, both real and metaphorical. Her work is a kind of heightened personal reportage that repays patient attention. Likewise, Eva Stenram‘s series entitled pornography/ forest_pics, which plays with found and constructed erotic imagery by digitally removing the naked bodies from the photograph. What remains is an empty landscape in which a blanket or bag or an item of clothing lies, mundane and innocent. In Drape, a related series of wilfully drab domestic black-and-white interiors, Stenram has posed women behind curtains, with only their legs on view. Again, the result is both playful and provocative – but not in the sexually loaded way of the images she has subverted.

Elsewhere, there was too much that was too familiar, and too little that suggested deep looking or, indeed, deep thinking. The French School turned out to be a celebration of the Ecole Nationale Supérieure de la Photographie in Arles rather than a unifying style. The school was created in 1982 by Alain Desvergnes, whose exhibition of Faulknerian landscapes and characters in Mississippi, made back in the mid-to-late 1960s, was another highlight of this year’s somewhat muted Rencontres d’Arles. Next year, one hopes, they will find a big name to impose a vision on a festival that momentarily, at least, seems to have lost its way – and its spirit of adventure.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.