Richard Long could have been named for his height: at 6ft 4in, he is craggily mountainous, with a giant stride and a pair of eyebrows that resemble bushes clinging to a rocky eminence. It is a physique suited to, and formed by, his art. As a student in 1967 he made a work called A Line Made By Walking – a photo of a narrow stripe of grass, flattened by the tread of his feet, through a meadow near his home in Bristol.

It was quietly revolutionary, for it claimed the act of walking as art. The very tread of his feet was the work: this was different from the Romantics’ interaction with the landscape, in which the art was, to quote Wordsworth, “emotion recollected in tranquillity.” According to Long, giving a rare interview in a book-lined room in his London gallery, Haunch of Venison: “The significance of walking in my work is that it brings time and space into my art; space meaning distance. A work of art can be a journey.”

Long, a vigorous 67 years old, has been walking ever since that youthful work, his steps mapping territories from Dartmoor to the Andes. On his journeys, he has arranged stones by roads, made circles from boulders, aligned pebbles in riverbeds, traced furrows in sand. From 23 June, a survey of his footfall – which he records through photographs or textual descriptions – will be on show at the Hepworth Wakefield. “My footsteps make the mark. My legs carry me across the country. It’s like a way of measuring the world. I love that connection to my own body. It’s me to the world,” he says.

Long, who won the Turner prize in 1989, seems to stand apart from much of the mainstream sculpture made in Britain today. His work can invoke the spectacular, but by way of its location rather than its monumentality. If Antony Gormley’s Angel of the North or Anish Kapoor’s ArcelorMittal Orbit tower are inescapable, you may have walked past a dozen Longs and never noticed them. Or they may have been there once, and disappeared into the tide or the shale.

“There is a point of view,” he says, “that if you go into the landscape you should only leave footprints and take photographs. The other extreme is making monuments. I have no interest in making monuments. But I think there is a fascinating territory between those two positions. I can move things from place to place. I can manipulate the world by leaving stones on the road. And they don’t disappear because the stone is still in the world – but completely anonymously.”

Which is not to say that Long eschews the large-scale. Some of his walks cover hundreds of miles. A 1998 work was a line of 33 stones, one placed each day “along a walk of 1,030 miles in 33 days from the southernmost point to the northernmost point of mainland Britain”. (It is a measure of his physical vigour that the walk works out at 31 miles a day.) “The idea that no one sees it is part of the work,” he says. “I can make it in a very remote place, almost secretly or in an isolated way. Maybe no one sees it, or a local person sees it and they don’t recognise it as art.”

Long’s walks are often feats of endurance, though he does not recognise them as such. He tells me about breaking his leg in the Cairngorms. Was he afraid? Long laughs. “No, it was just irritating. I just struggled out. It took me about four days to get out. I didn’t realise I’d broken it, and it was beautiful weather, and I pitched my tent and stuck my leg into an ice-cold stream for about two days. I realised I had to get out when the weather changed. I made a work out of it called Lull Before a Storm, Pride Before a Fall.”

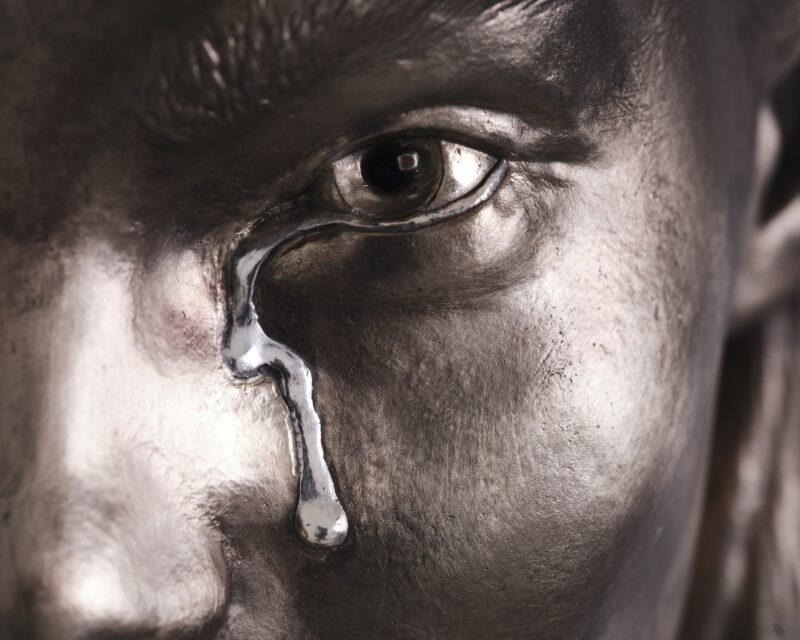

There is an immense simplicity to Long’s work. When making work in the landscape he uses only the objects he encounters. The works he makes specially for art galleries are slightly different in that he brings in materials, but they are invariably natural ones: mud and water, sticks and stone. For a gallery he might make a circle of Cornish slate on a floor, for example, or draw a line in wet mud on the wall and let “nature do the rest” as the liquid dribbles down. (He will make a new wall piece from damp china clay for the Wakefield exhibition.) He employs the two most basic and central gestures in human life: the line and the circle.

Long was born in Bristol in June 1945. “I am one of the few artists who makes work where they were born,” he says. He is also unusual in that his work is about the rural, the wilderness. He often walks through built-up areas, but, unlike the writer Iain Sinclair, for instance, he has no interest in recording them. “I am realist,” he says. “The landscapes that I have chosen to work in are the landscapes that still cover most of this earth; the world is still basically an empty place.”

He talks about the mud of the Avon forming him. “I was born with my feet in that material. That is in my DNA, that mud.” He is a self-confessed connoisseur of mud. Tidal mud, like that of the Avon as it cuts through Bristol, is best for his art, for it is “viscous”, whereas “mud in a field is not real mud”. He remembers the primal pleasure of making mud pies as a small child: making a circle of the soft, sticky stuff, then pouring water into the centre.

As a student he was thrown out of the West of England College of Art for being “too precocious”, he says. He calls it his “lucky break”, as the next stop was Saint Martins School of Art in London, where he was mostly left to his own devices.

He admired, and admires, his contemporaries Gilbert and George, but it was later, when he went to Europe, he says, that he found artists making work in tune with his: people such as Carl Andre and Joseph Beuys. When he made that first formative work, Line Made By Walking, “I knew I was doing something interesting. It was quite pleasurable to be doing something that was a little bit underground. It was the swinging 60s. To be walking lines in fields was a bit different.”

His story is different from that of the Young British Artists, who, he says, have their roots in pop art; they are postmodern in sensibility where he is modernist. “It was easy to be original when I was young. Pop art was dying on its feet. Abstract expressionism was dead. Henry Moore was just Henry Moore. My generation rewrote everything: land art, conceptual art, minimal art. It’s far more complicated to be original now. I was innocent.”

He smiles: “I was part of the generation that did things because they seemed like a good idea at the time – which they were.”

• Artist Rooms: Richard Long is at the Hepworth Wakefield from 23 June to 14 October

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.