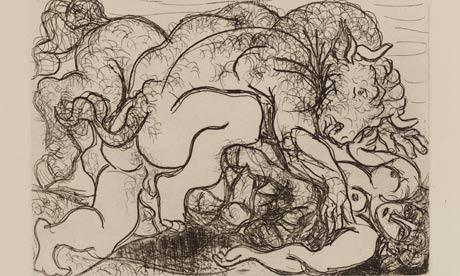

Art for thought … Picasso’s Minotaur lying over a female centaur, 1933; plate 87 of the Vollard Suite, British Museum. Photo: Keizo Kitajima/Succession Picasso/DACS 2011

Pablo Picasso is a geek masquerading as a matador. Picasso’s fame relishes his bullish persona. Photographed at bloody sporting events, or joking about in the studio, described by his biographers chasing and oppressing women, he comes across as a robust, to say the least, man’s man.

Picasso. We all think we know him. His art, too, ought to be familiar, after all this time. But to seriously encounter it, even for a moment, is to realise with a shock that none of those pop-cultural props help at all, for it is endlessly challenging, unexpected, and above all intellectual.

To put it another way, we imagine Picasso as a sensualist, yet his art is all brain work. He combines an accessible reputation with an obscure reality. Where some artists of today might sell themselves as conceptualists and present precious little thought to chew on, Picasso is famous as a worldly character – but his art is a maze of intelligence.

I cannot think of any other artist who so ruthlessly forces his beholders to think with him. It is impossible to enjoy a Picasso without using your brain: just to recognise what he is doing, what he is depicting, is to make a whole series of cognitive leaps. To spend time with a series of his works is to gradually awaken your visual brain and acclimatise it to the level his genius demands.

This holds true at the British Museum’s exhibition of his phenomenal Vollard Suite. The cerebral nature of this exhibition – the prints in the Vollard Suite are just black ink on white paper; the museum juxtaposes them with Etruscan mirrors and Greek vases to suggest classical sources for his mythological homages to the Mediterranean tradition – is a revelation of who Picasso really is, as an artist. He is not simple, that’s for sure.

There is a unique thrill to looking at Picasso. First, there’s a rite of passage: the dead wood of sloppy, everyday perception has to be cleared away. I select a familiar subject to get my bearings – a picture of a bullfight. But it is not familiar at all. The graceful lines that define a woman bullfighter as she slides between a tangle of horns and a horse’s screaming head have nothing to do with any cosy image I might have in my head of what a Picasso “looks like”. This is not an artist who has a simplistic “style”. He has his methods, but what he does with them here is specific and original: he is wrestling with something.

Soon, I start seeing Picasso as he demands to be seen – with a mind open to his complex investigations of the visual world and the inner imagination. Myths and desires and dreads inhabit his powerful psyche. The effort to make sense of his teasing images is immensely rewarding.

The pleasures of Picasso are fiercely intellectual – a banquet for your brain. Leaving the British Museum I feel as if I have just played chess with a master who generously let me win a few pieces before checkmating me with a smile. As always, it is a joy to lose.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.