the Battle between Good and Evil

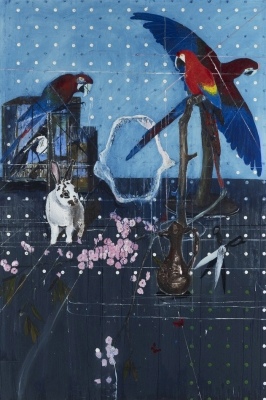

Three Parrots with Rabbit and Scissors

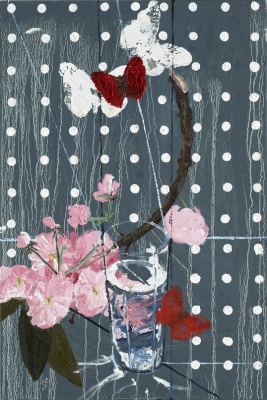

Blossom Water and Butterflies

The last time I saw paintings as deluded as Damien Hirst’s latest works, the artist’s name was Saif al-Islam Gaddafi. A decade ago the son of Libya’s then still very much alive dictator showed sentimental paintings of desert scenes in an exhibition sponsored by fawning business allies. Searching for some kind of parallel to the arrogance and stupidity of Hirst’s still life paintings, I find myself remembering that strange, sad spectacle.

There is a pathos about Two Weeks One Summer, in which Hirst shows paintings of parrots and lemons, shark’s jaws and foetuses in jars in a vast space in White Cube Bermondsey. It is the same kind of pathos that clings to dictators’ art. This is the kind of kitsch that is foisted on helpless peoples by Neros and Hitlers and such tyrants so beyond normal restraint or criticism they believe they are artists. I am not saying this to be cruel. There is a real analogy: Hirst like an absolute ruler must be utterly surrounded by a court of yes-people, all down the line from his painting shed to the gallery, if there is no one to tell him he is rowing himself to artistic damnation with these trivial and pompous slabs of hack work.

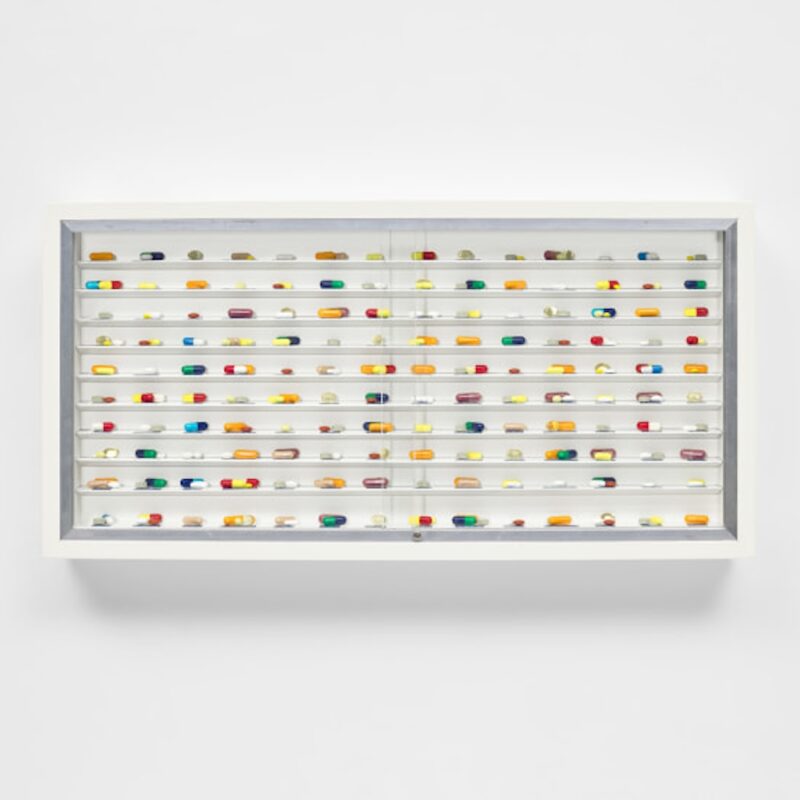

This is the third exhibition by Damien Hirst to open in London this spring, and it retroactively mocks the others. His retrospective at Tate Modern is brilliantly edited. It includes all the best vitrines, and none of the rotten “proper” paintings that he now makes at home in Devon. To paraphrase the epitaph on Albrecht Dürer’s tomb, whatever is immortal (or at least memorable) of Damien Hirst is in that exhibition. But here is the other side of the story: an artist so wealthy and powerful that he can kid himself he is an Old Master and have the art world go along with the fantasy. The most recent paintings here were finished this year, so the fantasy is still very much alive. So is the courtiers’ chorus of support.

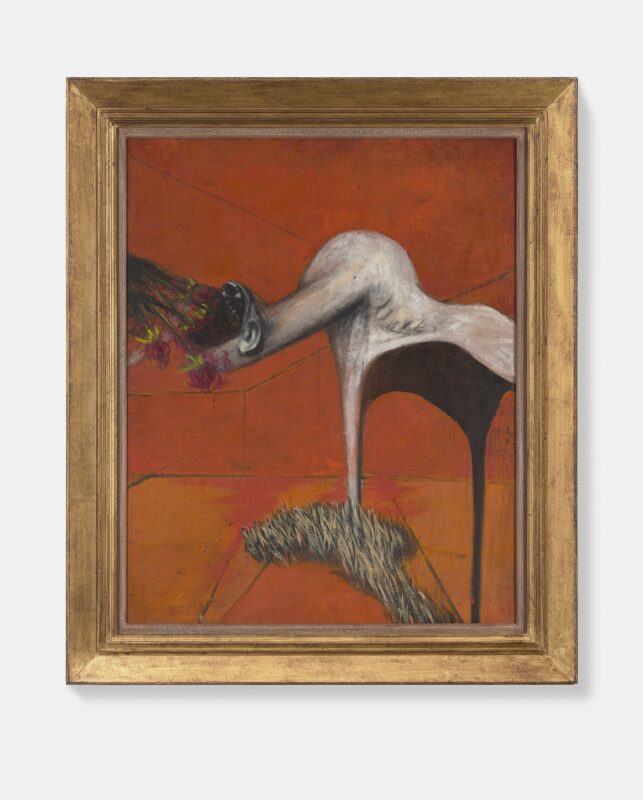

The exquisitely produced catalogue has an essay by a senior curator at the Prado in Madrid, who draws comparisons with Caravaggio and Velázquez. Yikes. It would be impressive stuff if we did not have the paltry reality of Hirst’s paintings before our eyes. At White Cube, I pass from picture to picture, trying not to crack up laughing or actually swear out loud. The exercise feels like a parody of being an art critic, for these are humourless parodies of paintings. Like the Prado expert I can spot the analogies – lemons, how Zurbarán – but they work only to destroy and humiliate Hirst’s daubs.

Seriously – Mr Hirst – I am talking to you. It seems you have no one around you to say this: stop, now. Shut up the shed. I say this as a longtime admirer, not an enemy. No encounter with a contemporary work of art has ever thrilled me like the day I walked into the Saatchi Gallery in 1992 and saw a tiger shark’s maw lurch towards me. But these paintings are abominations unto the lord of Art. They dismantle themselves. Each of these paintings – from the parrot in a cage to the blossoms and butterflies – takes on the difficulties of representational painting and visibly fails to come close, not merely to mastery, but to basic competence.

At least it can be said for Hirst that he shuns the cheap tricks of other contemporary painters. If he used the glib formulae so common in painting today, such as whimsical abstraction and projected outline images, he might get away, as others do, with a total lack of true painterly knowledge. Instead, in a bizarre act of historical arrogance, he seems to think that if he tries to paint like Manet, he is suddenly Manet. Hey – how rich was Manet? Not very, right? Well then … So he takes on the Great Tradition with none of the training and patience that made those guys what they were.

If Hirst did not try to paint an orange accurately, no one would know he can’t do it. But he has tried, at least I think it’s an orange, and the poor sphere seems to float in mid air because of the clumsy circle of shadow below it. For a moment I thought this was intentional, then I realised it was a competence issue. Such issues abound. You look at a branch and it is obvious he has worked at it: equally obvious the work was wasted. At their very best these paintings lack the skill of thousands of amateur artists who paint at weekends all over Britain – and yet he can hire fools to compare him with Caravaggio.

This exhibition is a warning to young artists. At 18, you may long to be Damien Hirst when he was 30. But in his 40s, Hirst apparently wishes he was the artist that, who knows, he might have been, had he spent his youth drawing day after day after day. He has left it too late. Instead he looks like a tyrant lost in a world of mirrors, like the world’s most overpraised child, like a disgrace to his, my, generation. Are we this bankrupt?

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.