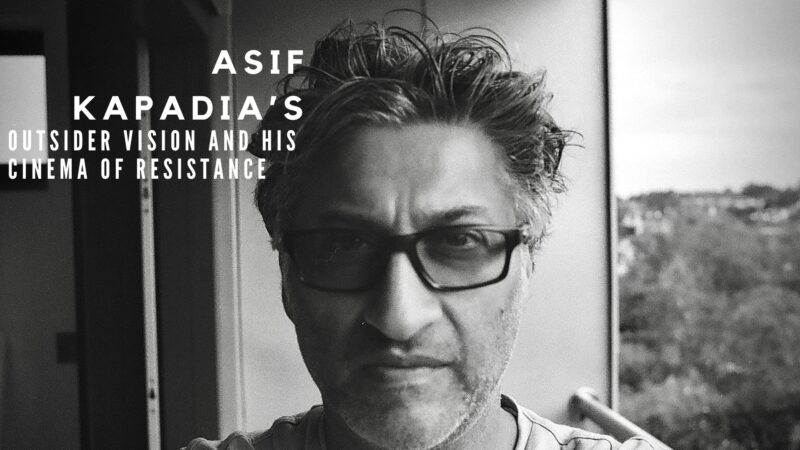

Lying in state: the ‘leader’, (Slawomir Sierakowski) is dead in Assassination, the third part of Yael Bartana’s Polish trilogy. Photograph: Yael Bartana/Marcin Kalinski

And Europe Will Be Stunned is a deeply stirring and contentious film trilogy by the Dutch-Israeli artist Yael Bartana, soon to open in Britain on its European tour. Each film is enough to disturb; together they are peculiarly subversive. I do not know exactly what they might mean to Jewish, Israeli or Palestinian viewers, still less to a Polish audience watching some of the scenes unfolding on the site of the Warsaw Ghetto itself. But my sense is that an anxious concern for other people’s reactions is at least part of the trilogy’s content.

In the first film, Nightmares (2007), a political leader strides into a Warsaw stadium to rally the crowds. “Let the 3 million Jews that Poland has missed… return to Poland, to your country,” he urges, acknowledging Poland’s antisemitic history but arguing that Jews and Poles should come together once more to extinguish the hatred.

But to whom does he speak: the Jews of modern Israel or the Jews of the past, murdered or vanished into exile? Apart from a small band of pioneers, there is nobody there. And time is flowing in both directions. For though he addresses the future, this man is standing in the past, in Warsaw’s old Decennial Stadium, weed-choked and derelict, its heroic protests against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia long forgotten; unless they are still to come. For the film reprises Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935), as if the Holocaust had not yet happened.

In the second film, Wall and Tower, now dressed as Jewish immigrants to 1930s Palestine, the pioneers build a settlement on the site of the Warsaw Ghetto. The digging of the foundations exactly resembles the digging of graves; the stockade is identical to a watchtower. What are they building, a settlement to keep people out, a kibbutz or another barbed-wire death camp? The settlers eventually rest on the grass. Filmed from above, they resemble a heap of dead bodies.

In the final part of the trilogy, the leader has been assassinated. Vast crowds attend his state funeral. A grey Soviet-style effigy has been erected and the eulogies are given in its shadow, along with further calls for a return to the homeland – but which? By now, that might equally be Poland or Israel.

Bartana was born in Israel in 1970 and educated in Amsterdam and New York. She won the 2010 Artes Mundi Prize for her explorations of Israeli national consciousness. Her films are stunningly well made, as they have to be in this case to appear immediately simple yet ultimately complex. To begin with, every symbol irresistibly recalls another and every analogy seems clear: foundations and graves, idealists and demagogues, Polish and German eagles, Communist and Nazi rallies. The armbands and vertical banners of the state funeral could speak of several 20th-century nations, and indeed the second film is set to both the Polish and Israeli anthems.

Both songs yearn for freedom for the people of the land; each has a sense of pride based on national distinction. Indeed, the third film, which rings with opposing views, raises the question of whether the Jews who settled in what became Israel were so different from anyone else in a century of nationalism. But then again, Nationalism = Terror according to a funeral banner.

Every scene has its historic counterpart by association or inversion: that is the obvious interpretation. But the experience of watching these films as works of art is altogether different. Each feels like a trauma played out in the form of a nightmare, plausible, sequential, even logical until the sleeper awakes, baffled and horrified by what he or she saw. How is it possible for Polish antisemitism to have persisted after the Holocaust that took place on its soil? How is it possible for Israel to have occupied Palestinian territory? Here is the sleep of reason.

Bartana’s films swim between fact and fiction. They move seamlessly from one genre to another, from documentary to biopic to Riefenstahl. The performances are remarkable, especially that of the leader Slawomir Sierakowski – both patently a performance (he is occasionally seen dropping his eyes to a script) and yet somehow authentic.

Everything appears both real and unreal. Study the credits and you will find that this is profoundly true, that the actors performing the roles are also playing themselves. Slawomir Sierakowski really is a Polish political thinker, the writer Alona Frankel really did flee Poland in the 1950s and return to Warsaw to play herself in the Polish trilogy, and those multicultural crowds really have come to hear the speeches at Sierakowski’s “funeral” because they are involved in JRMiP, the Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland.

As for this movement, one has assumed it to be a fiction all the way through, a hallucination conceived as part of the drama. Yet it has a website, a manifesto, a conference and enough followers to fill a vast Warsaw square. By the end of the cycle, with its superb performances and poetic shifts of idiom, its time games and its haunting soundtrack of distant voices, one is no longer so certain of the movement’s status.

After all, if so many Israelis have their ancestral roots in Poland, and Poland is so prepared to back Bartana that it chose her trilogy as its official entry to the last Venice Biennale , then perhaps there is something to the JRMiP. That idea is raised, however briefly, however absurdly, to make one think hard even as Bartana’s films portray the agonising complexity of Polish-Jewish history.

Elizabeth Price is as committed an artist, in her way, as Yael Bartana. But her thoughts are devoted to cultural history, and to modernism in particular. Several of the films in her Baltic show – shortlisted for this year’s Turner prize – scrutinise modernist pieties. I particularly liked At The House of Mr X, in which the words of an unseen guide, arriving on the screen in motion script, take us round the pristine former home of the make-up magnate who gave us Outdoor Girl gloss and Miners Smokey Eyes.

The guide becomes badly over-excited by the juxtaposition of Mies van der Rohe chairs and shot-silk foundation, Achille Castiglioni lamps and Mercury Dust eyeshadow. Eventually they become whipped together in a whirl of words and images so that each becomes newly bizarre: the furniture and faces of two eras brought strangely together.

The Baltic has some of Price’s more theoretical works but it is also showing her most popular film, User Group Disco, a droll black-and-white blend of B-movie, French critical theory and Antiques Roadshow, in which bric-a-brac revolves on a turntable to a script of pompous rhetoric from sociology to software. Words and images are deftly spliced to satirise the sinister and accentuate the positive. It made me think of Ferdinand Léger’s dynamic 1924 film Ballet Mécanique.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.