In the foyer of al-Riwaq gallery in the grounds of Doha’s Museum of Islamic Art, a young Qatari girl hugs a huge furry sculpture by Takashi Murakami. The gallery is hosting a retrospective of the Japanese artist’s work, and the scene could be a snapshot of globalised culture: a huge inflatable self-portrait of Murakami in a Buddha pose looms in the background as the girl’s parents, her mother wearing a face-covering niqab, sip lattes and take photographs.

This is a show on an epic scale. Along three walls of the main gallery runs a 100m-long painting in acrylic, gold and platinum. Huge inflatables of Murakami’s signature cartoon characters, Kaikai and Kiki, hover over a circus big top; inside, a cinema screens the pair’s animated adventures battling flatulent space monsters and an alien armada.

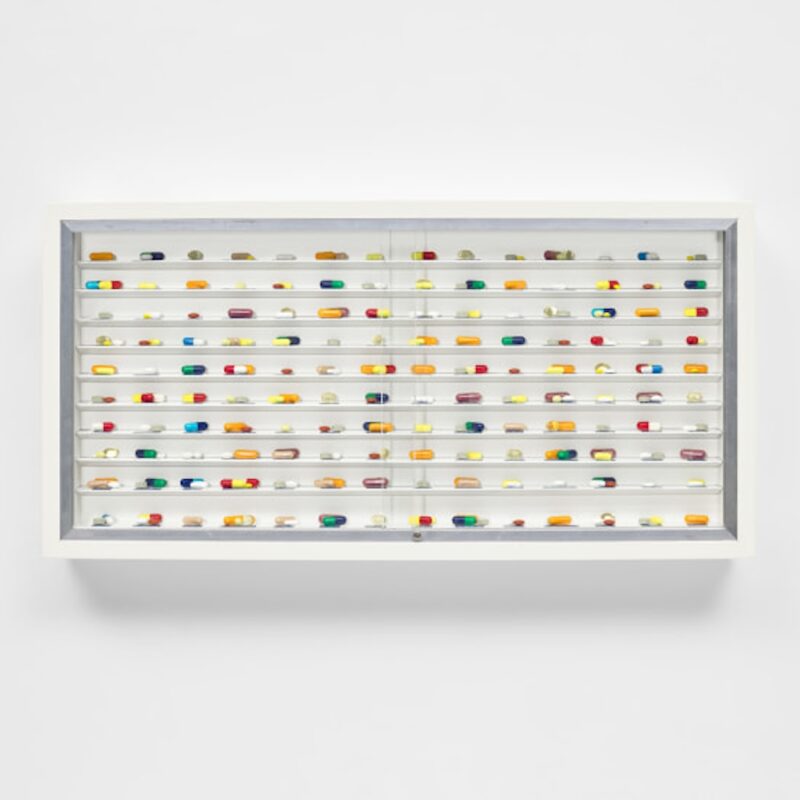

The ambition of Qatar’s latest contemporary art show, aptly entitled Ego, is matched only by the country’s spending power. Last year it was ranked the world’s biggest buyer of contemporary art by the Art Newspaper. Over the past seven years, the Qatari royal family has spent an estimated £1bn on western art. Recent acquisitions are believed to include Mark Rothko’s White Center (Yellow, Pink and Lavender on Rose), bought for £45.9m in 2007, Damien Hirst’s pill cabinet Lullaby Spring, bought for £9.7m in the same year, and the last privately held version of Paul Cézanne’s The Card Players, bought in 2011 for £157m, a record price.

Purchases such as these have helped secure the oil-rich state’s rise as a major player in the art world. Larry Gagosian, widely regarded as the world’s most powerful art dealer (and rumoured to have bid £139m for The Card Players), was among the 200 dealers, collectors and curators who attended the opening of the Murakami show in February. The Qatar Museums Authority (QMA) sponsors Damien Hirst’s Tate Modern show, due to travel to Doha next year, while the Qatar Diar real estate company is sponsoring the Shakespeare Schools Festival. Renzo Piano’s Shard in London is 80% owned by Qatar’s central bank, with its royal family expected to use two floors. Meanwhile, the foreign ministry has supported cultural events worldwide, including in Syria, Kazakhstan, Turkey, India and China.

This huge investment testifies to an ambition to transform the country into a cultural hub rivalling Paris and New York. At the forefront is Sheikha al-Mayassa al-Thani, the 28-year-old daughter of the emir and head of the QMA, who has overseen the development of several museums to showcase Qatar’s collections of Middle Eastern, Islamic and international art. Last June, nine months after her father pondered acquiring Christie’s auction house, she hired its chairman Edward Dolman as director of her office. Al-Thani was named the most influential person in the art world by Art+Auction magazine last year, which noted she “has the resources of an entire country at her disposal. They have hired Ed Dolman to be their personal shopper. And the budget has no limit.” In her forward to the catalogue for Hirst’s current show, the sheikha, who studied political science and literature at Duke University in North Carolina, writes that her organisation has been “laying the ground for Qatar to become a leader in making, showing and debating the visual arts. (…) Art – even controversial art – can unlock communication between diverse nations.”

Critics of the nascent scene in Qatar and its neighbour the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which now hosts two major international art events, Art Dubai and the Sharjah Biennial, and plans to open both a Louvre and a Guggenheim museum by the end of 2017, believe the focus on contemporary art comes at the expense of a grassroots scene. Hans Ulrich Obrist, co-director of the Serpentine Gallery in London, thinks there is a real danger posed by the “homogenising force” of globalisation. “The danger is things start to look the same. Local voices disappear if [culture is] just an import. But if there’s a hybridisation it could be fascinating.” Hassan Sharif, who exhibited at the Venice Bienale last year, as an example of such hybridisation. Considered the father of the UAE’s contemporary art scene, his drawings are inspired by Arab calligraphy; while his mixed media sculptures (sliced up rubber mats, twisted cutlery) marry ideas of the readymade with UAE’s disposable consumer culture.

Sharif, 61, studied at the Byam Shaw school of art in London in the early 1980s. Speaking at his studio in Dubai’s suburbs, he says, “I had difficulty finding an audience for my work. But I knew I should not blame society. Our art history is very short. The first public art exhibition was by a group of school students who decided to show their drawings and paintings in the central library in October 1972, less than a year after the UAE was formed.”

Obrist believes Qatar and the UAE are undergoing a cultural evolution akin to that of postwar Los Angeles. He believes Qatar has been smart in developing museums, including the Islamic art museum, the Al-Riwaq contemporary gallery and a National Gallery, due to open in 2014, that have established connections between a local heritage and international contemporary visual culture. “In Doha, a visionary museum experience has been built up in the last three years. In Los Angeles it took 20.”

Still, walking around al-Riwaq, you are struck by the lack of visitors. There were five people at the exhibition when I visited on a Thursday, mainly foreign tourists. In contrast, the Islamic museum, with its huge collection of historical manuscripts, textiles and ceramics, is bustling with locals. Mathaf, the Arab Museum of Modern Art, is also empty when I visit. The picture is similar in the UAE. At the Sharjah Art Foundation‘s March Meeting, a regional gathering of artists and academics, architect and government official Khaled Bin Saqr al-Qasimi says: “Wherever you go, the art audience that is local is small or non-existent. Most of the local people at exhibitions are friends of the artists.”

Jean-Paul Engelen, the Dutch director of public art at the QMA, says education is key to encouraging local interest. The former contemporary art specialist at Christie’s also thinks that, given the country’s conservative politics and Islamic customs, they will try to avoid exhibitions that might shock. “I think this [Murakami] show is easy entry level because they all think it’s a family show and a visual spectacle,” he says, noting that the local audience has had very little exposure to contemporary art. “They probably see things in there that you or I wouldn’t.” (This presumably does not include Murakami’s bejewelled condom-wrapper in the mouth of his psychedelic cartoon-head sculpture The Simple Things.) “It’s not about making the most thought-provoking academic theory,” he continues, “it’s about starting a conversation and widening horizons. We are introducing a new language, we don’t have to start with the swear words. In Europe, we didn’t go from Michelangelo to Damien Hirst in a decade.”

Indeed, the Hirst show currently at Tate Modern will not be exactly replicated in Doha, with pieces such as his installation A Thousand Years, featuring a maggot-infested cow’s head, likely to be omitted. A QMA spokesman tells me, “We are planning to launch an extensive education programme to introduce Hirst and his work to Qatar’s community. Curatorial decisions will obviously take into consideration the cultural sensitivity of our community towards some works that may appear offensive or repulsive.”

Across the border in the UAE, such debates recently overshadowed Art Dubai. Local authorities ordered at least four pieces removed from display in advance of a visit by the ruling family, including a painting based on the image of Egyptian soldiers beating a woman in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, her abaya robe ripped off to reveal her blue bra. At the press launch, the event’s director, Antonia Carver, says it is not political.This sentiment is echoed by Frederic Sicre, partner at equity fund manager Abraaj Capital, which sponsors the event’s main art prize, who suggests the Arab Spring “is old news”. But when we speak later, Carver denies there is an aversion to political work, noting that last year’s event included a performance by a group of artists who were reacting to events in Tahrir. A year after the uprisings across the Arab world, regional artists “don’t feel the need to pander to a desire to make political work for the west”, she says later on. She points to one of the five winners of this year’s Abraaj Capital prize, Raed Yassin, whose work China depicts scenes from the Lebanese civil war on porcelain vases as an example of “a more nuanced vision”.

William Wells, director of the Cairo-based Townhouse gallery, disagrees, saying the level of censorship was unprecedented. He blamed the Arab uprisings and a blasphemy scandal that hit last year’s Sharjah Biennial for the authorities’ “incredible nervousness”. (In 2011 Sheikh Sultan bin Mohamed, the ruler of Sharjah, the UAE’s most conservative emirate, sacked the biennial’s artistic director, Jack Persekian, after artist Mustapha Benfodil’s installation of mannequins in T-shirts with anti-Islamic phrases was displayed in a public courtyard near a mosque.)

Judith Greer, the Sharjah Foundation’s American associate director of international programmes, says: “There’s no sense that we only produce work that the Emirati audience is happy with but you have to think how you push the boundaries. People will question if they want their children to wander around the biennial.”

Despite the debacle, Wells praises Sheikha Hoor al-Qasimi, the 32-year-old daughter of the emirate’s ruler, for transforming the art foundation after studying at the Slade and the Royal College of Art in London. “If you had seen the biennial in the 90s it was so sad. Everyone was over 75. But Hoor realised that discussions, presentations, raising questions was the way to energise it.”

Hoor al-Qasimi, president of the art foundation, says: “The exposure to the vigorous scene in London had a significant impact. The fact that it is all free, and that one can go to countless galleries and museums in an afternoon, was, and is, important to me.

“I’ve tried to create a platform that supports artists in the production of their work, while helping to facilitate their interactions with Sharjah and its audiences here.”

She denies there has been local resistance to the biennial, but adds: “I would say that there have been times when some people have been ‘disinterested’ in some of the more difficult or challenging work.”

The rulers of Qatar and the UAE want to stimulate a contemporary art scene on a par with London or New York, with the profiles of Doha’s museums, Art Dubai and the Sharjah Biennial rising to rival Tate Modern or the Frieze art fair. But this burgeoning art scene is still driven more by money and the will of the ruling elite than the cultural affinities of their people.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.