Rachel Swainston

Made spot paintings for Damien Hirst in the mid-1990s, before becoming an upholsterer.

Painting spots was very dull. There’s not a lot you can say about them. The canvases would arrive; they’d be stretched and pinned. Damien would specify spot size and we would mark them up and draw them. Then we’d have a massive delivery of household paints, which we’d mix into smaller pots of whatever colours we needed. We’d have hundreds of colours: no two were ever the same. A six-foot square canvas with spots four inches apart would take about a week. Every painting was sold.

It was quite simple really, just a formula. Damien didn’t need to have much input. Most of the time, there were two of us, although it would depend on how quickly he wanted them churned out. We were just the small fry. I came out of Goldsmiths [University] thinking I can’t do anything, so I did these. Although they were all hand-painted, meaning each one is imperfect, there is no individual quality to the painting.

Lots of the Old Masters had people doing things for them. Damien created the idea; we just did the manufacturing. It would have been nice to have been credited in some way. We didn’t feel he was particularly grateful, but it’s quite a nice thing to be able to say you have done. Whenever my kids do a project on famous artists at school, they always do Damien Hirst. It means they can say: “My mum did the spot paintings.”

Kerry Ryan

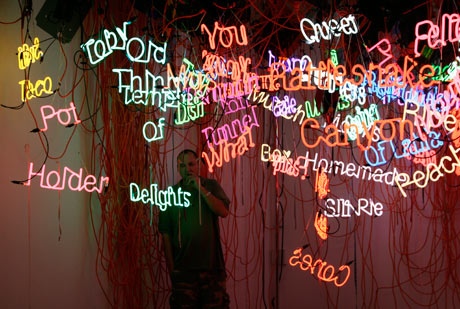

Has been making neon signs for more than 20 years, for artists including Tracey Emin, Anselm Kiefer and Mat Collishaw – as well as shops and restaurants.

About 20 years ago, Tracey Emin and Cerith Wyn Evans came into my shop in Spitalfields, London, separately, to ask for neons. It seemed to be getting used more and more in art. The first piece I made for an artist was the word EXIT backwards, TIX3, for Cerith, then a neon for the Tracey Emin Museum in Waterloo, then a piece for Sarah Lucas, a neon coffin she called New Religion. I now make all Tracey’s neons for the UK and Europe: drawings and whole sentences in her handwriting.

I started nearly 30 years ago, via an apprenticeship on Brick Lane, when I was 16. Working with artists has inspired me to be more artistic myself. It’s nice to see the transition from sketch to finished piece on the wall of a gallery or a collector’s house. So I’ve been making my own work – in neon, metal, vinyl. I’ve also, over the years, worked out how to make underwater neon, which in theory you can’t do but I found a way. It was for putting in fish tanks, although not all fish can cope with it. We tried electric eels, piranhas, all sorts. But we found that carp are tough enough.

Because neon is such a specialist field, I end up being a sort of consultant as well as a fabricator. For example, I have to explain that there are some things that just cannot be made in neon: it can’t do folds or corners; it has to be curved or rolled. Conversely, I sometimes find myself suggesting even more risk-taking. I do feel essential to the process.

Working with artists is easier than working with people who want a sign for their restaurant or shop. Most artists tend to know exactly what they want, and tend to respect people who know their trade. They also understand materials and processes, as that’s what they think about all day.

Art is all about the idea now: I think using fabricators makes art more valid and not less, from a conceptual point of view. If an artist has an idea, it can still take a lot of work to realise. As far as I’m aware, no artist who uses fabricators ever sits on their behind and lets other people get on with it. I don’t know any people who work harder than artists.

Paul Vanstone

Former stonecarver for Anish Kapoor. He now exhibits his own work.

Anish Kapoor’s work is very boring to make because it’s so methodical, so precise. Changes could be measured in millimetres. There was a lot of to-ing and fro-ing. I’m a bit more random with my own work.

Anish is very good at making things himself: he knows what’s what. But carving is very physical. He could use a stonemason but prefers to use an artist, so he obviously wants that artist’s sensibility. I ended up going to quarries for him, driving across Spain looking for materials. That was fabulously useful, the sort of thing you never learn at art college.

The common analogy is that you wouldn’t expect an architect to build his own building. Constantin Brancusi worked for Auguste Rodin, Anthony Caro for Henry Moore. It’s understandable: you absorb or reject the skills of what comes before you, and then hopefully find your own voice. At the same time, you can’t imagine Francis Bacon handing over his paintings to anyone else at any point. One thing that has changed with fabrication is that a lot of the artworks are like executive toys. They’re just so controlled. In my own art, I look for more of a dialogue.

Mike Smith

Has made work for artists including Jake and Dinos Chapman, Mona Hatoum, Rachel Whiteread, Mark Wallinger and Damien Hirst.

The most difficult piece I’ve worked on was probably Monument for Rachel Whiteread because it was so fraught. The piece, which sat on the fourth plinth at Trafalgar Square in 2001, was 11 and a half tons of polyurethane resin, carved into two pieces and made to look like a mirror image of the plinth. We worked on it for three years and then it was on show for six months. If we were to do it now, it would be easier because of the way materials and processes have developed.

It’s pretty annoying how little people understand the processes of making contemporary art. Many of them would be horrified if they thought that photographers didn’t take their own photographs. But how do they think Henry Moore made those bronzes? It’s a lot like making a large car or a truck. I think there’s a lack of understanding of the process. There are people who latch on to the fact that artists are not making things themselves. There are even trained art historians who take issue with it. That’s the scary thing. The moral outrage – the idea that we’re all being duped because we’re paying all this money for work that’s not being made by the artists themselves – is ridiculous. What’s more interesting is whether a piece is good or bad.

Steve Farman

Negative cutter on major films from Lassie to Batman Begins. Worked on Tacita Dean’s Film, recently shown in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, re-cutting the original negative after it had been wrongly cut and permanently damaged by a different neg cutter.

The Tacita Dean piece was the highlight of my career. I’m 52 now and I’ve been doing this since I was 17. It was the film I’ve had the most approval for. I felt appreciated, not just a very small cog in a massive machine. And Tacita’s film was such a mess. As I recut it, I was saying: “Oh God, you can’t have this bit – but you can use that. This bit’s got marks on it, but you can use it – it makes it look more like film.”

We started at midday on a Tuesday and she stayed with me until eight the next morning. I remember, at a reception for the piece, somebody asked how long I’d known Tacita, and I said we spent the night together last Tuesday.

That was my first major foray into the art industry. Compared to the film world, people are much nicer. They’ve got time to be nice because it’s much slower paced. It was a bit surreal for me because I’d always been in the background. I remember, while working on [Wolfgang Petersen’s] Troy, I only managed to speak to the third assistant director, not the director, not the first assistant director, not the second. That’s the difference.

I’m of a different generation. If I stop, then effectively there’ll be nobody left in the UK doing negative cutting. The 23-year-old editors working today have never touched film; they have no idea what it can do. Someone asked if I knew how a certain part of Tacita’s work had been done and I said: “Oh yes, that piece of film was put through the camera 13 times.” And they said: “Why wasn’t it done digitally?”

It’s a touchy-feely thing. Tacita still wants physically to touch the film. But as it’s such an expensive medium, artists are the only ones willing to go down that route – because they love it.

Rungwe Kingdon

Runs Pangolin foundry in Stroud, Gloucestershire, one of the largest in the country. It has cast work for Eduardo Paolozzi, Lynn Chadwick, Damien Hirst and Antony Gormley.

I tried to be a sculptor and, although I could make all sorts of things, I recognised that I didn’t have a language. Skilful people can make anything, but that doesn’t mean it will be made well or can touch a large number of people. The language has to be distinct. A good fabricator can take an artist’s language and work with it, a bit like a translator.

I’m not interested in how many assistants Rodin had. I’m interested in his language, his vision. Big artists have a big language – and Rodin’s was monumental. Before him, it was tight, talented and dead, everyone worrying about the last hair.

Getting credit has never bothered me in the slightest. We’re silent collaborators. We don’t have the big ideas ourselves. We’d be ridiculed if we tried. There are a lot of mediocre artists and I didn’t want to be another one.

I won’t work for just anyone. I have to get into their language, understand them. We solve problems. Some artists will come to us and want an exact reproduction of a model. Others aren’t very practical: they might come with some amorphous idea and want us to grab hold of the smoke. We help them fit their ideas into a practical reality. You go through very long periods of incubation, working on drawings with the artist. Once you get an image you have to try to fit it to a material. There is the technical challenge and the challenge of interpreting ideas

I don’t think we should be surprised if the general public think it is fraudulent. What’s really important is that things are made with integrity. If the artists pretended things were all their own work, that would be fraudulent. But we deal with artists, not charlatans.

• This article was amended on 11 April 2012. The original omitted the line “re-cutting the original negative after it had been wrongly cut and

permanently damaged by a different neg cutter”. This has been corrected.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.