Malevich (2011), Mixed media, 200 x 100 x 200 cm. Photo: Pangolin London / Steve Russell

Malevich (2011), Mixed media, 200 x 100 x 200 cm. Photo: Pangolin London / Steve Russell

1.If you weren’t an artist, what else would you be?

Perhaps a chef. I enjoy cooking – I’m really into Lebanese and Iranian food at the moment, though Spanish dishes are the ones I probably cook the most.

2. Can you tell us more about your work and what are the main ideas you would like to express?

The work I make falls somewhere between painting and sculpture, and the weight of history and theory of those two disciplines permeates into it, but I try to challenge and play with that rather than being trapped by it.

I’m very interested in loss and memorialization. Death is the universal fear that so much art has historically grappled with and I suppose my work continues in that vein.

I try to create tensions: between decision and chance, geometry and disorder, inside and out. Almost any painterly process has an unavoidable performative aspect to it and that’s something I embrace but I never give explicitly to the viewer. The work they see is the aftermath, the legacy.

3. How do you start the process of making work?

Ideas tend to come in a rush. I always have a notebook on me to scribble them down in. I’m not one of those artists who can methodically make a coherent series of works, the process of making inevitably sparks off ideas for a whole host of diverging new pieces, even before I’m half way through.

The making process itself can be a source of inspiration too. While it may not always immediately inspire, experimentation with new materials, processes and techniques gives a wider array of means by which to realise future ideas.

Packet RY (2010), Mixed media, 200 x 250 x 30 cm. Photo: Adam Walker

Packet RY (2010), Mixed media, 200 x 250 x 30 cm. Photo: Adam Walker

4. Do you consider the viewer, when making your work?

Not especially. I’m interested in what they get from it when they see it, but the making process is entirely inward focussed.

5. Name 3 artists that have inspired your work?

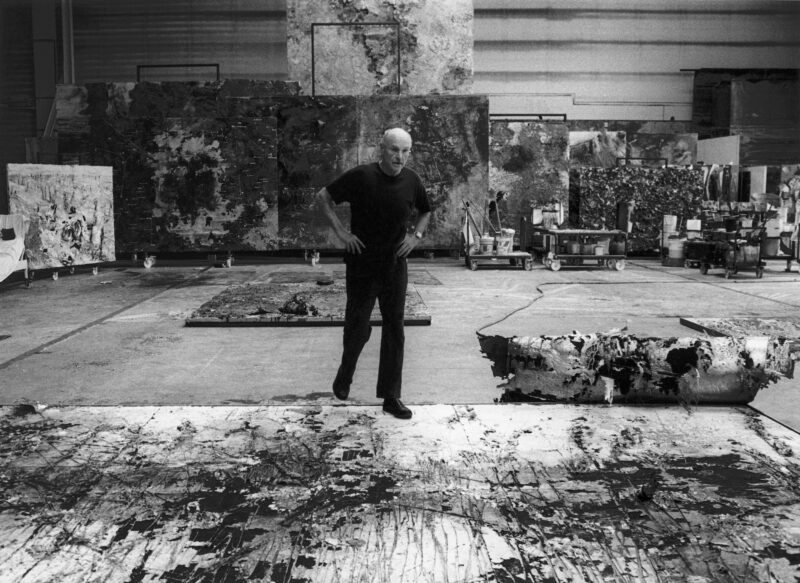

Anselm Kiefer, who’s paintings I was in awe of as a teenager. I suppose the sense of loss and melancholy that pervades his work still resonates strongly in my own.

Mark Rothko, for that sense of sublime, transcendental power and Zen-like total immersion.

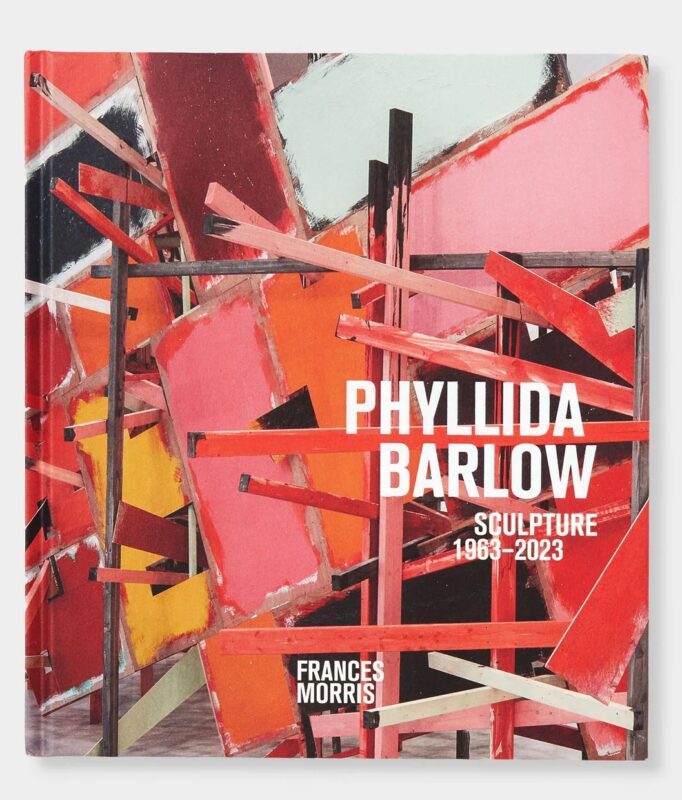

Phyllida Barlow, for the way she manages to create size and scale while at the same time keeping the work so light and entirely un-monumental.

6. Name 3 of your least favourite artists.

Dali. I’m put off by his politics, but also just find that hyper-realism uninteresting – everything’s over explained.

Damien Hirst. Good on him for making a fortune, and some of the earlier works were interesting, but where’s the integrity in repeatedly mass-producing the same populist commodities?

Magritte. As I grew up in Brussels people seem to think I must like him, but I just find it a bit trite and uninteresting, same as with Dali I suppose.

Sealed B (2011), Acrylic & gloss on canvas, plastic, 180 x 70 x 180 cm. Photo: Adam Walker

Sealed B (2011), Acrylic & gloss on canvas, plastic, 180 x 70 x 180 cm. Photo: Adam Walker

7. What defines something as a work of art?

Simply that someone has placed it in that context. Once it’s there others can agree or disagree, but being art to one person is enough to define it as such. It’s a bit of a meaningless label really. Whether something’s good art is a very different question.

8. In times of austerity, do you think art has a moral obligation to respond topically?

No, not a moral obligation. I think any residual link between ‘art’, ‘moral’ and ‘obligation’ has been rapidly declining since the Renaissance.

I’m interested in politics and lean to the left, so I tend to be drawn to art which challenges and critiques rather than plays to the establishment, both artistic and socio-political.

I think art plays a vital role in its own context, in its aesthetics and concepts and the thought processes they can initiate in the viewer. A wider, social, political and cultural context for art is interesting – some art can become something more when it’s considered in those terms and can have great impact in those areas, but there’s always the danger the art itself can become lost within the wider context.

9. Anytime, any place – which artist’s body would you most like to inhabit?

Caravaggio – he led a crazy, wild life and his paintings are so forceful and cinematic.

23 by 21.5 (2012), Pigment on canvas, 115 x 120 cm. Photo: Adam Walker

23 by 21.5 (2012), Pigment on canvas, 115 x 120 cm. Photo: Adam Walker

10. What is your favourite ‘ism’?

I’ve studied a lot of isms and at times probably become a little too in thrall to them. They’re important to study and reflect on, and do inform my work, but ultimately I’m an artist making an artwork not an academic writing a paper. I’ll say antidisestablishmentarianism, I used to think it was the longest work in the dictionary when I was a child. I don’t know if it’s even a real word actually.

11. What was the most intelligent thing that someone said or wrote about your work?

I was in a show Marcus Harvey was curating and we had some conversations which made me realise that contradiction, mess and unresolvedness was a strength in the work rather than a weakness, and something to embrace rather than resist.

12. And the dumbest?

How do you get the floor clean afterwards?

13. Which artists would you most like to rip off, sorry, I mean appropriate as a critique of originality and authorship?

These days with so many people making art and there being so many ways to see and discover it, it’s inevitable you’ll find other artists doing things that seem to be similar at first glance. Angela de la Cruz was a big influence a couple of years ago, though I’d actually arrived at the work I was making before I saw what she was doing. I’ve recently seen some work by a German artist called Christine Wurmells which seems to have a few similarities to some of my practice, so I’ll have to look into what she’s doing a bit more.

I think originality can become a bit of a false idol – it’s unlikely you’re going to be completely, earth-shatteringly new, so learn and be inspired by others but ultimately just keep on pushing what you yourself are interested in.

14. Do you care what your art costs? State your reasons!

Art and money, it’s an uncomfortable relationship isn’t it?

I wouldn’t want playing to the market to ever become a factor in the work I make. I’d much rather have to do something else in order to make a living and make work with integrity than have to compromise my work in that way.

15. If Moma and the Tate and the Pompidou wanted to acquire one of your works each, which would you want them to have?

The three pieces from the past couple of years which I think have been most successful are Malevich, 12.5 by 62 and Sealed B, so they can fight it out between themselves for those three.

Memorial to the Grand Surrey Canal (2011), Mixed media, 300 x 500 x 300 cm. Photo: Dom Ridout

Memorial to the Grand Surrey Canal (2011), Mixed media, 300 x 500 x 300 cm. Photo: Dom Ridout

16. What’s next for you?

I’ve been moving out of the studio and gallery, making large site specific sculptures like Memorial to the Grand Surrey Canal which deal with loss and aftermath but in a wider cultural context rather than just an art historical one. I’ve got a few potential new projects in that vein that I‘m working on.

And there are also a couple of upcoming shows. The specifics are just being confirmed, but they’ll be listed at www.adamwalkerart.co.uk when all finalized.