Reflection (Self-portrait), 1985 Private Collection, Ireland © The Lucian Freud Archive. Photo: Courtesy Lucian Freud Archive

I arrived at the usually sedate National Portrait Gallery to be confronted by a throng of eager reporters, photographers and film crews from as far afield as Japan, testament to the popularity of one of the greatest British artists, the late Lucian Freud. The baying hacks surrounded the affable NPG Director Sandy Nairne, as he introduced the press preview of ‘Lucian Freud Portraits, describing it as “A living exhibition planned with the artist”, which came from a 2006 conversation with Freud followed by several years of planning, and not a memorial show to Freud who passed away last year at the grand old age of 88. Nairne explained that they had also worked closely with Freud’s long-standing Studio Manager and friend David Dawson, who is the subject of the painting that stood on Freud’s easel when he passed away.

Planned as part of the Cultural Olympiad, this exhibition is a countdown event for the London 2012 Olympics. The scale and scope of this unprecedented retrospective is ambitious, and befitting of an artist who will surely go down in the history books as a Master of realism. There are 130 paintings and works on paper on display, gathered from museums and private collections all over the world, some seen here for the first time.

A chronological hang gives an insightful tour of the stylistic development of Freud, from a 1940 portrait of his tutor Cedric Morris, and a series of finely detailed portraits of his first wife Kitty Garman created with miniscule brushes smaller than a man’s baby finger, through his first naked portrait of 1966 (‘Naked Girl’) to his final unfinished painting of Dawson with Eli the dog. National Portrait Gallery Contemporary Curator Sarah Howgate pointed to evidence of the evolution of the painter on display in the exhibition, from his early use of fine brushes in images such as ‘Girl with a Kitten’ (1947) and ‘Girl with a White Dog’ (1950-1), through a period of transition when he began to paint standing up, resulting in the more rigorous brushstrokes evident in his later work.

Girl with a White Dog, 1950-1 Tate: Purchased 1952 © Tate, London 2012

What is striking about ‘Girl with a White Dog’ (1950-1) is the flat application of the paint, and the delicate brushstrokes portraying the equally delicate aureole of the bare nipple which has evaded the loosely tied yellow dressing gown. Freud’s early style possesses an observational intensity that he pursued to the end, and this particular painting possesses a graphic treatment of anatomy and drapery reminiscent of Ingres’s 1808 ‘Valpinçon Bather’. Freud pays great attention to capturing the folds in the dressing gown, the drape in the background, the translucency of the pale skin, and the shadows cast by the clavicle. Indeed the art historian Herbert Read once described Freud as “the Ingres of Existensialism’. Kitty’s disarmingly large eyes invite the viewer into the canvas, whilst she gazes slightly into the distance, her distracted expression perhaps indicative of their imminent divorce in 1952.

A room near the entrance of the exhibition features a series of tender portraits of Freud’s mother Lucie, following in a tradition of artists painting their mother’s. ‘The Painter’s Mother’ (1982-4) is an intimate portrayal of a frail, elderly Lucie on a hospital bed, the thinly layered paint perfectly capturing the translucency of her ageing skin. In the same room is a rare drawing of Freud’s Father.

Chief Curator of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas, Michael Auping explained at the press view that Freud told him a little about his relationship with his mother, who was by all accounts a very insightful woman. Freud had confessed that his Mother “Could figure out what I was thinking before I thought it”. He had decided to make up for a distant earlier relationship, by inviting her to sit for him in his studio in her later years, resulting in some of the most poignant images in the exhibition.

‘Hotel Bedroom’ (1954) is the last painting Freud executed whilst sitting at an easel. A penetrating double portrait of Freud with second wife Caroline Blackwood, Blackwood’s pale and sad face emerges from the white sheets of a bed in the foreground, whilst Freud stands in shadow in the background, confronting the viewer. In the mid-1950s Freud ditched the easel and began to paint standing up, replacing the fine brushes with coarser brushes made of hog’s hair. This resulted in a far freer painting style on a grander scale.

Auping explained: “When he got up out of the chair and his brushstroke became much more active and broad. He got much more interested in skin.” He continued: “I would ask Lucian often ‘Why the nudes?’ He would say every time ‘It’s the most complete portrait of a person’.”

This intimacy between subject and artist is something that appears in the early portraits, all the way through to his final works, and indicates the importance to Freud of painting people who were part of his life, however transient their presence in his story was. As a grandson of the Father of psycho-analysis Sigmund Freud, perhaps it was inevitable that his painter’s gaze should be so intense and penetrating, as if attempting to delve beneath the surface of the skin to the inner psyche. When he painted someone, he really got to know every part of them, body and soul, and this is what gives the paintings such power and presence. He himself said “I work from people that interest me and that I care about, in rooms that I live in and know”.

There are rooms devoted to subjects that were prominent in Freud’s work at different stages of his life, including the late Leigh Bowery and his friend Sue Tilley, the subject of the iconic 1995 painting ‘Benefits Supervisor Sleeping’, which sold at auction in 2008 for $34 million, the highest price for a Freud painting, and the most expensive painting sold by a living artist at auction.

Benefits Supervisor Sleeping, 1995 Private Collection © The Lucian Freud Archive. Photo: Courtesy Lucian Freud Archive

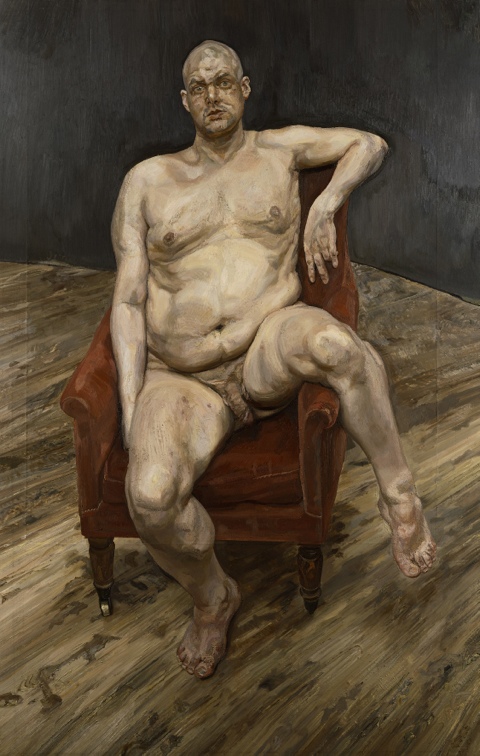

Curator Sarah Howgate chose to display the paintings of Bowery in a small room near the entrance of the exhibition, explaining: “I wanted to give a sense of them being painted in the studio”. Howgate talked of the first time Australian performance artist Leigh Bowery sat for Freud, when he automatically disrobed in the studio, providing the artist with a majestic torso capable of carnivalesque poses. The resulting painting ‘Leigh Bowery (seated)’ (1990) is a magnificent, larger than life canvas perfectly suited to a larger than life character. Bowery was a stalwart of London’s louche Soho club scene in the 80s and 90s, and his influence as club promoter, actor, model, designer, pop star had a profound impact on fashion, music and art. His infamous club night ‘Taboo’ later became the subject of a musical of the same name, penned by Boy George and destined to immortalise Bowery on the Broadway stage.

Leigh Bowery (Seated), 1990 Private Collection © The Lucian Freud Archive. Photo: Courtesy Lucian Freud Archive

Bowery is one of the only subjects of Freud who gives as good as he gets, confronting the painter and viewer with a powerful stare. Bowery displays such confidence in his naked form, with one leg splayed nonchalantly over the arm of a red velvet armchair, that one is reminded of Goya’s ‘La Maja desnuda’ (Naked Maja) of 1797-1800. Freud met Australian performance artist Bowery in 1990 at the Anthony d’Offay gallery, where he was giving a week-long performance that captivated the art world, including Freud who asked him to sit for him. Freud said of Bowery: “He was so intelligent, instinctive and inventive, also amazingly perverse and abandoned.”

Bowery introduced Freud to Sue Tilly, or ‘Big Sue’ as she was affectionately known, and she became the Rubenesque star of several important works on display here including; ‘Sleeping by the Lion Carpet’ (1996), ‘Benefits Supervisor resting’ (1994), ‘Evening in the Studio’ (1993), and the afore-mentioned ‘Benefits Supervisor Sleeping’ (1995). Her ample flesh was attractive to Freud and enabled him to really get his teeth into the medium of oil paint. “You can see he really enjoyed painting the flesh”, observes Howgate. Indeed there is a denser application of pigments in these later nudes that serves to embrace the plentiful folds of skin.

Up close to ‘Evening in the Studio’, the paint has a visceral quality, and the impact of Tilley’s physique is emphasised by positioning her naked on the hard wooden floor in the painting’s foreground, juxtaposed with a comparatively frail female in the background, who sits in a chair next to a camp bed, covered in a blanket, her fully clothed state in stark contrast to Tilley’s ample bosomed nudity. The canvases of Tilley are raw and unforgiving, with Freud examining every crevice and flaw of her flesh, such honesty evoking the dimpled back and posterior of the nude in Courbet’s ‘Les Baigneuses’ (1853). Freud had examined the work of Courbet and said of him: “I looked at the Courbets a lot: Les Baigneuses, that marvellous nude going into the forest, like a rugger player pushing off others…I like Courbet. His shamelessness.”

The only other country to have the privilege of hosting this landmark exhibition will be the USA. Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth Curator Michael Auping stood in a room full of Sue Tilley paintings, and talked about the importance of Freud to an American audience: “It was very important for us to bring this show to America, because we have nothing like this. We are the land of Photoshop. We are the land of no wrinkles. And if you look at the history of American art, it’s an American art of flatness and distance. If you think about the painting ‘American Gothic’ (1930) by Grant Wood, you get the sense of an American psyche, or think of Edward Hopper who looked at many of his nudes not from within the room, but from another room. So Freud’s is a kind of painting that we think of as a kind of ‘exotic other’ that we don’t have.”

The exhibition culminates with a final section, which could be described as Freud’s ‘Golden Age’. It contains portraits from the last 20 years of his career, a mixture of nudes, head shots and fully clothed portraits featuring family members including Fashion Designer daughter Bella, prominent art world figures David Hockney and critic Martin Gayford, David Dawson and friends such as Sally Clarke, owner of a restaurant near his Holland Park studio, which he frequented daily.

Freud only ever worked from life, spending days and nights in his studio, capturing on canvas a never-ending queue of sitters, who were willing to be immortalized by the great Master, despite his warts n’ all approach to depicting the human body. Freud claimed “I could never put anything into a picture that wasn’t actually there in front of me”, and the result of this dedication to realism is a powerful body of work, which thrusts both the beauty and beastliness of the human form into the viewers gaze with no holds barred.

Clarke spent a lot of time in the kitchen, and consequently possesses a pair of rosy red cheeks, which she usually covered with make-up. However in Freud’s typically honest style, he depicts her with a barefaced portrait, ruddy cheeks and all. His portrait of daughter Bella is equally honest, and demonstrates a mutual respect between father and daughter, with her dressed in sombre black polo neck and trousers, the only bare skin on display her shoeless feet, powerful hands and pensive face.

This section of the exhibition shows the diversity of Freud’s output, with fully clothed and nude subjects from all walks of society, in a variety of shapes and sizes. “Freddy Standing” (2000-1) features a tall, sinewy man with prominent ribs, in contrast to the fuller-bodied torso of Dawson. There are skinny women with protruding hipbones, as well as fuller-bodied females. However the only portrait of a black body is the nude female of “Naked Solicitor” (2003).

Freud’s subjects included celebrities such as Jerry Hall and Kate Moss, and iconic figures such as The Queen. Although none of these portraits are on display here, one of his favourite sitters Sue Tilley was given the Royal seal of Approval, when The Duchess of Cambridge visited the exhibition in her capacity as the new Patron of the National Portrait Gallery. Tilley summed up meeting the Duchess by saying, “I’m not embarrassed about her seeing me naked – I’m a human being”. Which is exactly how Freud treated each of his sitters, bringing out their humanity and capturing it on canvas for posterity. Curator Howgate sums up the exhibition in a nutshell, saying: “It’s very much a life in paint, rather than a biographical exhibition”.

It is not a common perception of Freud’s work that it was particularly humorous, however there is evidence of humour in the unusual compositions and perspectives of paintings such as ‘Sunny Morning – eight legs’ of 1997. A naked Dawson lies on a bed holding a dog, whilst two legs stick out from beneath the bed. Howgate cites this as an example of his sense of humour, explaining “There is playfulness in his paintings. They’re not all serious. He was humorous”. Freud had in fact painted a mirror image of Dawson’s legs protruding from beneath the mattress.