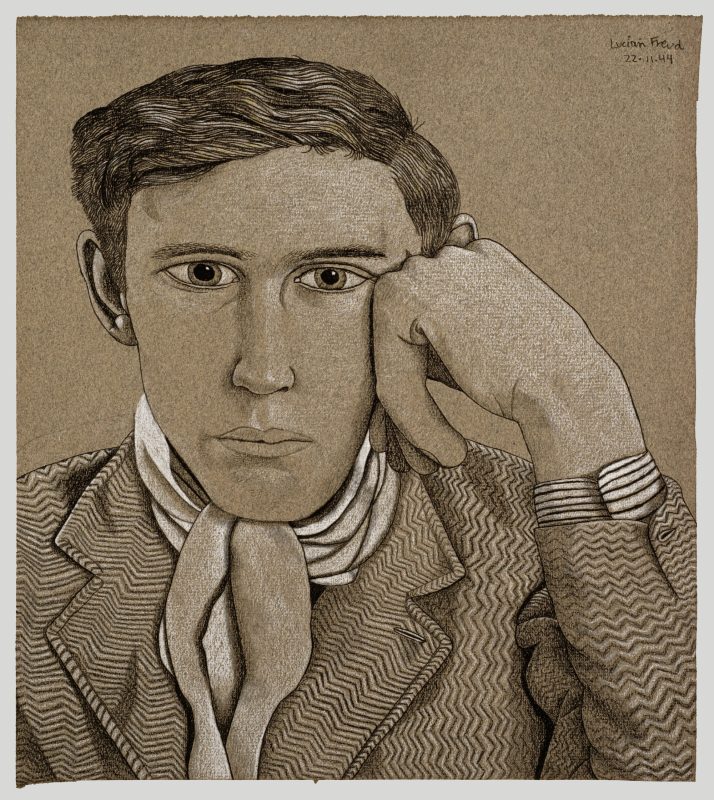

Lucian Freud Portraits is the final act of a prodigious career. Freud was still working on the show until his death at the age of 88 last summer. A whole floor of the National Portrait Gallery has been cleared away for the labours of a lifetime and the experience is grave, mysterious, compelling and inexhaustibly strong right up to the last portrait, where the brushstrokes simply cease mid-sentence.

What was Freud’s true subject all these years? The book of his art seems to be open in this monumental show, beginning with those early portraits that appear almost Flemish in their cold acuity. Here is Freud’s first wife, Kitty, with her wistful fallen rose hanging opposite his self-portrait, hawk-eyed behind the barrier of an outsize thorn.

Here is his second wife, Caroline, limpidly beautiful in 1952: are there any more shining eyes in art? But within two years he has become an anxious shadow, in the devastating Hotel Bedroom, ousted to the window’s edge by the vast bed in which she lies, eyes now swollen. He looks at us, she looks away: an impasse of guilt and irreversible pain.

Recognisable faces emerge: Freud’s dark-eyed daughters Esther and Bella, his assistant David Dawson, the artist Celia Paul, garments laden with paint (his and hers, in witty reprise). A pictorial narrative develops through poses – the newborn’s fists balled above its head, the grandmother dying in the same position – and through the entrances and exits upon the studio stage.

Big Sue arrives from the benefits office, her proud mountain of flesh a source of awe and fascination. The huge Irishman – surely one of Freud’s greatest subjects – his face a magnificent scrum of ruck, thrust and knuckle, wills himself into temporary composure in a too-tiny chair. The performance artist Leigh Bowery cocks a leg, monumental and defiant, lending a terrific grandeur to his own forked nakedness as he does to the painting. What is the source of the portrait’s power: sitter or artist? The question irresistibly presents itself from work to work.

Freud the modern master looks at home in the marble grandeur of the National Portrait Gallery; his ostensible genre is supposedly portraiture after all. But with the 60s, and surely with the example of Stanley Spencer’s nudes, on public display at last – think of those portraits of Patricia Preece where the brush carries an obsessive charge as it inches his way across her bared body – Freud expands, or defies, the conventions of portraiture.

The naked ape, unidealised and depicted with extreme concentration on physical essence and fact is generally held to be Freud’s main contribution to 20th-century painting. Bowery wears his nakedness like a trait, flaunting his tower of flesh, but performance was of course his metier. The enduring question – the crux – is what is made of the nakedness of other people.

If you couldn’t tell a Freud by the freight of creamy paint, you might recognise it from the pose: naked bodies spreadeagled on a bed, sprawled on rags, huddled on a chair, twisted, splayed, genitals slumped or parted at the picture’s apex, heads leaning or lolling, eyes down or averted beneath Freud’s own gaze as he stands over them.

It is sometimes said that the poses were found by the sitters themselves – force of circumstance when offered nothing but a chair, or just the bare floor itself. But Kitty Epstein spoke of being “arranged”, and whatever his sitters did at first is superseded by everything the painter does later.

This show is like the group portrait of a species: lifelong observations of the human animal. The paintings look quite particular close up, which Freud’s dramatic brushwork demands. Here a toenail gleams blue with paint that exactly mimics the enamelled carapace of nail polish. There a scar indents a fleshy cheek with a silvery line. The hair on Dawson’s chest is soft as a rabbit’s scut compared to the rougher fur of the whippet that dozes in his lap.

But in broad terms these life paintings offer a generality: that whatever we are is contained in a bag of skin, that our external being is all flesh. And that flesh is generalised in Freud’s naked paintings. Some bodies are more obviously boneless, others more bruised, but there is a consistency of substance and the palette (as far as I can see) rarely changes: the same livid green and yellow, dust blue and chromium white, the raw red of chafed inner thighs, the sheeny pearl of stretchmarks.

Of course the surfaces differ through time, worked and reworked, cumulatively corrected and revised until even the slenderest and most agile of sitters – including Freud himself – may appear massive, roughed up, the head carrying a huge burden of paint, the ankles thickening with ballast, brought down to earth. But the way Freud puts a body together – flesh strained over joint, muscle pulling this way, then that, colour fused with brushstroke – means one perceives the paint before the person every time. It is a reversal of the usual convention, the brief illusion that the portrait is a person first, however fleetingly, before reverting to a picture. That denial feels most emphatic when the subject is naked.

Looking at these paintings more completely, at full stretch, new aspects strike: rare mirth and pathos, odd spells of boredom, unexpected quickenings of interest, above all a strangeness of vision and scale. That is there in the way Freud paints children as dolls and society hostesses as gigantic made-up masks, less like women than transvestites. It is in the muckle head he gives his newborn baby, bruised as a heavyweight fighter.

It is not to be supposed that Freud did not see this – his superb draughtsmanship is the cynosure of precision throughout. It feels in fact as if all these anomalies are evidence of absorbed and protracted staring.

The baby, as the curators subtly note, hung for decades at Chatsworth before anyone discovered the baby was Freud’s; indeed, how could anyone tell? What he felt, what was going on: so much remains undisclosed. Sue lies rucked on the floor, while a woman knits impassively behind her. One man stands on a bed while the head of another protrudes tortoise-like below: sadistic or fortuitously comic?

Eagle-eyed, wary, blurred in the mirror, piercingly self-mocking: the man in the self-portraits always gives as good as he gets. Did Freud ever paint anyone more brilliantly than he painted himself? It seems from this show that there are more rivals than one thought.

The – clothed – portraits of Jacob Rothschild, Sally Clarke and Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza are superb, especially the latter. There he sits, a shrewd Croesus slumming it among the famous studio rags, struggling to hold a dignified pose, fingers flexed like the clawed feet of the mock throne: a restless magnate entirely out of place and ready to start for the exit.

That final gallery is full of surprises. The Bramham children, both clutching a duck, a real pathos in the little girl with her thick spectacles bewildered by Freud’s scrutiny. His own portrait at 80, such an accretion of nubbed and pelleted impasto you could pick it up by the nose; like late Titian or Cézanne, Freud is still experimenting.

Above all, you feel his curiosity flare before Louisa (unusually – significantly – named) who is herself palpably resistant. She holds her own, never quite submitting to the process and the whole painting rises to her level of self-possession, from the matt gleam on the old leather chair to the daylight kissing her tense young face. Louisa was more than a body: there was force of personality to be observed and transformed into something new: the substantial life of painted matter.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.