Yayoi Kusama once said she wanted to obliterate the world with polka dots. There have been dots on canvases, on walls, on naked bodies and on giant sculpted fruit. At her Tate Modern retrospective, bloated, ketchup-coloured inflatable balls decorated with white spots hang from the ceiling and lurk about the entrance. They attract infants, but repel adults like me. Kusama is difficult. Her dots spatter the walls and furnishings of a living room with UV-lit Day-Glo stickers. You want to bat them away like flies, but you can’t.

An artist of extreme and extremely variable works, Kusama is a phenomenon. She has been a maker of happenings, orgies and performances, and a political and sexual activist; she performed a theatrical gay wedding in New York in 1968, designing a conjoined polka-dotted outfit for the happy couple. She has been an installation artist, dress designer, art dealer, sculptor, pianist, poet and novelist (at least 18 novels, as well as an autobiography). Phew.

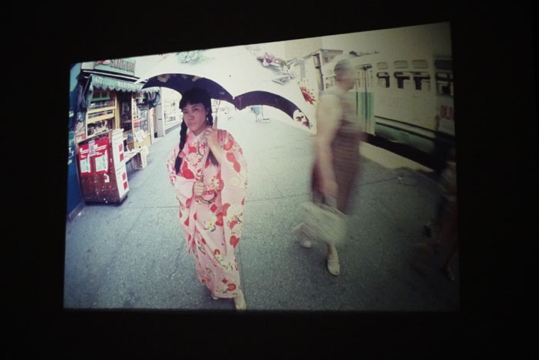

Ranging from the exquisite to the eye-wrenchingly brutal, Kusama’s art is hard to take en masse. There is nothing halfway about what she does, nor has there ever been. Now in her 80s, she still works every day in her large Tokyo studio, across the street from the mental institution where she has lived quietly since 1977. Art has been a way of coping, and of delivering herself from both her inner problems and from those around her. She was ambitious from the first, for her art as much as herself. Championed by Georgia O’Keeffe and Lucio Fontana, Kusama also had close relationships with artists Donald Judd and Joseph Cornell. She seems to have had multiple lives.

Her inflatables do nothing to prepare you for her early watercolours, oil paintings and other works made in response to her formative training in the traditional Japanese Nihonga style. (This was promoted by the dictatorship during the second world war, and became associated with Japanese nationalism.) Born in 1929, Kusama grew up wanting to be an artist, but was forced to work during the war, like many school-age children, in deplorable conditions in a factory. She also suffered from hallucinations from an early age. Family life was difficult, even as her reputation in Japan grew.

Her early works have a disturbing intensity and concentration. She painted barren landscapes, knotty things like tree roots or guts, decaying and rotting sunflowers in a field, vertiginous webs of lines, globular cells that might be distant planets.

Moving to the US in 1957, Kusama ended up in New York. There, she developed a singular body of works: her Infinity Net paintings, which fill a room here. You almost need to rub your nose as well as your eyes in them. These are paintings of great delicacy, and of almost unbearably laborious execution; the grand white and off-white surfaces sing with tiny circles and arcs of pigment, the skeins of white playing off yet another veiled colour beneath.

Sometimes the paint thickens in gnarly excrescences, then fades back again into the rhythm of repeated marks – which cover canvases much bigger than the artist herself. The largest Kusama ever painted was 10m wide. Imagine her covering all that ground, day after day, in her small, repeated notations. The effort must have been as daunting as it was therapeutic.

Judd, at the beginning of his career as an artist, lived in the same building as Kusama. They became lovers, and encouraged one another’s art. Her white Infinity Net paintings are almost minimalist, although her rigour had another purpose: staying sane.

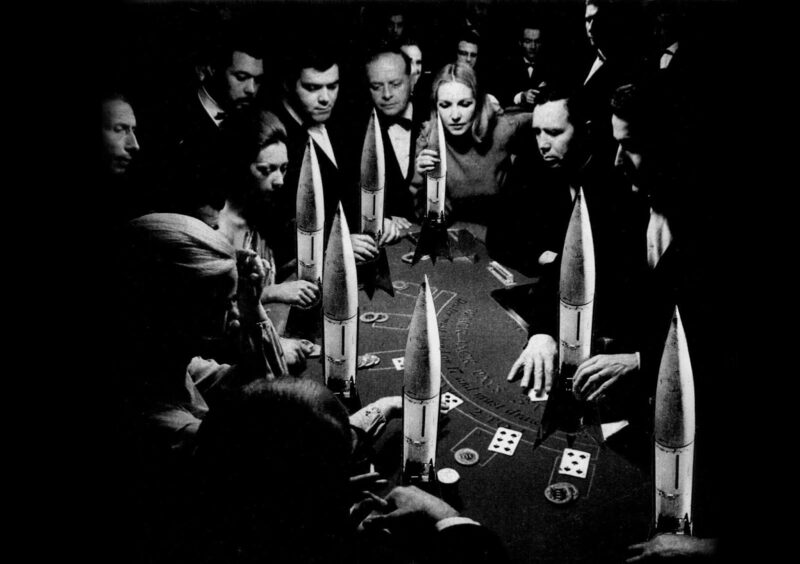

Later, Judd was to help her fabricate works which, instead of being obliterations, she called Accumulations. Shoes, cupboards and chairs, even a rowing boat which she and Judd found somewhere on the New York streets, began to sprout white, stuffed fabric phalluses. Cocks grew everywhere, like funghi in the dark. Later, they grew plant-like, resembling some writhing, undersea life. Kusama’s boat now sits spotlit in a room whose floors, walls and ceiling are papered with repeated photographic images of the boat itself, printed on black paper. Peer into the boat and among the white, lumpy penises are a pair of high heels. Kusama has said she has a fear of the penis.

By the time Kusama left New York in the early 1970s, she was arguably more famous than Andy Warhol. Returning to Japan, she was quickly forgotten by the art world she had left behind, though her work undoubtedly influenced, in small ways, both Warhol and Louise Bourgeois.

But still Kusama went on working, and in 1993 was the first woman to represent Japan at the Venice Biennale. In 1998 she was interviewed by Damien Hirst, who himself has been covering the world in dots, doubtless influenced by Kusama. One difference between Kusama and most so-called outsider artists is that she has been a consummate insider; her work, rather than being stuck in a singular track, has developed and changed through her entire career. There is always a sense of variation, of shifts in medium, scale and substance. The same intensity pulses through them all.

Kusama’s installations have become ever more grandiose. At Tate Modern, an entire furnished living room – dining table, crockery and glasses, chairs, the floor, walls, mirrors and paintings – is submerged in purplish light, where coloured dots fluoresce under the UV lamps. Kusama is singing something on the TV in the corner: I’m Here, But Nothing is the title of the work.

The dots are far from joyful. A blizzard of sensation, they make the room unhomely and threatening; they make me wonder what the experience of psychosis might be like. In 1965, Kusama made a room covered entirely in mirrors, turning the space into a chamber of infinite reflections. She has returned to this form many times, becoming more baroque as technology and money have allowed. In a disorientating mirrored space towards the end of this retrospective, little LED lights multiply into forests of glowing light, shifting in colour and intensity. Infinity Mirror Room – Filled with the Brilliance of Life is captivating, but feels like a sort of trick, as you disappear among your own reflections. Kusama’s best trick has been to stay alive, but more than that, her art has a palpable energy and a sometimes malevolent intensity – however playful it seems. It has a kind of truth.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.