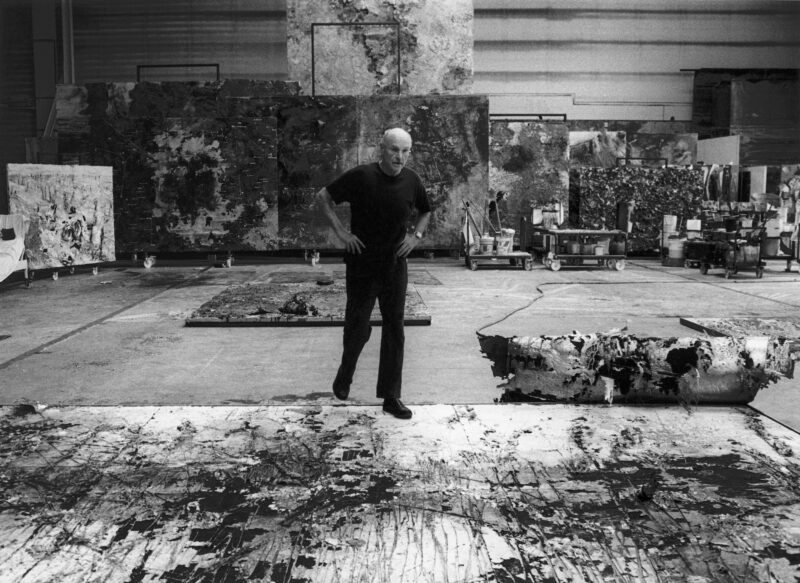

Anselm Kiefer works on a grand scale. On Friday the artist will sign a contract to buy the Mülheim-Kärlich reactor, a decommissioned nuclear power station near Koblenz, Germany. And on the same day Kiefer, one of Germany’s most celebrated postwar artists, will attend the opening night of his biggest show ever in Britain, spread over 11,000 sq ft of the newly opened White Cube gallery in south London.

Kiefer’s art is deeply serious, dense with both esoteric symbolism and political meaning. The show, Il Mistero delle Cattedrali, takes its title from a 1926 book by Fulcanelli, a mysterious figure who practised alchemy, and contains monumental paintings and sculptures alluding to ideas from the philosopher’s stone to the second world war.

“Art is difficult,” says the 66-year-old firmly. “It’s not entertainment. There are only a few people who can say something about art – it’s very restricted. When I see a new artist I give myself a lot of time to reflect and decide whether it’s art or not. Buying art is not understanding art.”

Kiefer, 66, misses the days of the 70s and 80s when art collectors such as Donald Fisher – founder of the Gap clothing stores – took a year to decide whether they wanted to buy a work or not. He refuses to allow his works to be auctioned, or even for his gallerists to discuss the art market with him.

Though he has been acclaimed by critics such as Simon Schama, who called him “incapable of producing trivia”, and was the first artist since Georges Braque in 1953 to make a work to go permanently on show at the Louvre, Kiefer regards himself as underground compared with artists like Damien Hirst, who he says makes “anti-art”.

But he’s at pains to point out that this “anti-art” is itself part of art. “Art has something which destroys its own cells,” says Kiefer. “Damien Hirst is a great anti-artist. To go to Sothebys and sell your paintings directly” – as Hirst did in 2008 – “is destroying art. But in doing it to such an exaggerated extent, it becomes art. I liked this action, the Sotheby’s sale, and the fact that it was two days before the crash made it even better.” In fact, Hirst’s auction, which netted £93m, and the collapse of Lehman Brothers happened at the same time, 15-16 September.

It sounds as though Kiefer, who was born in the Black Forest but has lived in France since 1991, endorses Charles Saatchi’s view that the art world is eurotrashy, vulgar and masturbatory. “He described himself, no?” says the artist, laughing uproariously. “[These days] art becomes fashion, it becomes [financial] speculation, but Saatchi started it.”

Ever since his first famous work Occupations (Bezetzung), in which Kiefer, then a student, photographed himself giving the Nazi salute in different locations around Europe, the artist has interrogated Germany’s relationship with its dark past. One room in the current exhibition includes four enormous paintings depicting Tempelhof airport in Berlin, which closed down in 2008. Built in 1927, the Nazis intended the enormous structure to be their gateway to Europe in Albert Speer’s redesigned Berlin. It was described as “the mother of all airports” by architect Norman Foster.

“Germans want to forget [the past] and start a new thing all the time, but only by going into the past can you go into the future,” says Kiefer.

At the moment, he complains, “they have fashion shows at Tempelhof and all this nonsense. There’s an office, an ice skating rink – it’s trivialising. I wrote [Berlin’s cultural department] a letter, saying ‘In the cathedral, you don’t bicycle.’ I spoke with Norman Foster and he said it was a pity they didn’t do something dignified with the locality.”

For instance? “They could give it to me. I could invite five or 10 artists and we could do something there, or they could do exhibitions, or use it as a private airport like Le Bourget in Paris.”

What prevents this, says Kiefer, is that Germans don’t distinguish between Nazi architecture and Nazi art. “Nazi art is really horrible, it’s boring, but the architecture of the 30s isn’t specifically German, it was the architecture of its time. Speer was a bad politician, but he wasn’t a bad architect.”

After unification, says Kiefer, Berlin should have been rebuilt along the lines planned out by Speer for Hitler, in the way that Paris wouldn’t exist in the way it does without Georges-Eugène Haussmann, commissioned by Napoleon III to modernise the city, “but in Germany it’s difficult – they are afraid of taboos”. He adds that the Berlin wall – “or part of the wall” – should have been left intact as a memorial, “and this empty space between east and west. I believe in empty spaces, they’re the most wonderful thing.”The White Cube show features images of apocalypse and regeneration, of alchemical scales, Stuka-like bombers and sunflowers, heavyweight both literally (Kiefer often works with lead) and figuratively.

An artwork was also planned for the outside wall of the gallery, but decided against at the last minute. “It was too busy there,” says Kiefer. Not that he worried about it being damaged by the public: “they can touch it, they can spray on it, I don’t care.”

Indeed, his pieces are often weathered by the elements – for instance, a giant, rusty satellite dish protrudes out of one painting.

Kiefer says that the current turmoil in Europe influences his thinking and the meaning of his work, “but you cannot see it immediately in the paintings – I am not a daily political artist.”

He approves of Angela Merkel. “I’m very happy that a woman is in power, I think they are better. We [men] are inferior.” Merkel, he says, “doesn’t want to be charismatic – she does her job in an old, Prussian way, and that impresses me. She decided to save Europe, and for that I must congratulate her.”

He is fervently pro-European, a theme which he says “pushes me”. “On a cultural level, we need Europe,” he says. “Germany alone is not good.” He says that he’d like to see Europe like the USA – “I would go so far” – with regions like Île-de-France, Bordeux and north Germany the individual states within it. “It doesn’t mean that you lose any [region’s] specific individual charisma. Europe is a big political organisation and then you have all these countries – it’s wonderful, no? We need Europe in an aesthetic way and a political way, and Merkel is now on the right way.”

So what of the power station? Kiefer professes himself amused by the fuss that ensued when he announced that he was buying the Mülheim-Kärlich reactor, since “that’s what I do all the time: I buy old factories, I move in I transform them and then I leave them and give them to some collector as I did in Germany and the south of France.”

He denies that the decision to buy the building was influenced by the Fukushima disaster, and says that standing inside the power station’s cooling tower was “overwhelming. It’s so wonderful it’s like the Pantheon. It will be a challenge for me to do something with it because it’s already very good.”

It’s all part of his mission to confront the past. “In Germany, if something is finished, they like to flatten it, bring it down, make the grass grow over it. That’s no good. You should keep these old buildings because they played a role and they can teach us something. I’m against the idea of bringing all these power stations down. I said, ‘I’ll take them all if you want’.”

Anselm Kiefer Il Mistero delle Cattedrali at White Cube 144-152 Bermondsey Street, London SE1 until 26 February 2012

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.