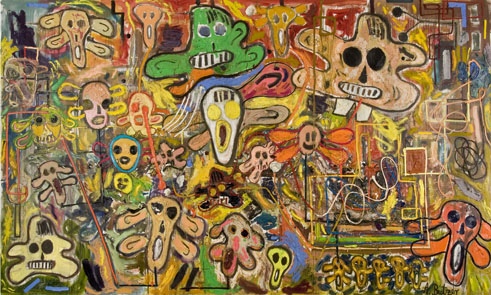

Ahnenbild 2411 2006 Oil on canvas 280 x 460 cm Image courtesy of the Saatchi Gallery, London © André Butzer , 2006

All credit to Charles Saatchi. He has bought (and sold) enough international art of late to mount museum-scale shows that bring entire nations into some kind of focus for a British audience. He began with America, then moved to China, India and various countries of the Middle East and is now exhibiting the work of 24 artists from Germany on all three floors of his gallery.

Gesamtkunstwerk represents Saatchi’s purchasing power too, of course: his recent outlays, risks and bets. It takes a sharp interest in the market; you might say it depicts the market to some extent. But it also offers an experience of contemporary art that few of us will see without travelling to Berlin at least, and it’s one in the eye for Tate too, being the kind of show that none of our public museums can afford.

By coincidence (or perhaps not?) Saatchi is showing a predominantly young German scene just as Tate Modern is showing the old, in the person of Gerhard Richter, whose works Saatchi collected long ago. Strangely, there is no crossover. Richter’s immense influence over succeeding generations – his intellectualism, his historical reach, the meditative depth of his photo-based paintings – is nowhere apparent at the Saatchi Gallery. This art goes in different directions altogether.

So that is something to bear in mind if you’re looking for a comprehensive survey. A strong and enduring strain of German art has been bypassed in favour of works large or loud enough to fill these palatial rooms. The paintings are the size of billboards and fully as blatant. The sculptures rise high or sprawl by the metre along the floor. The predominant look is trashy, heavy-handed, wilfully unbeautiful and chaotic.

Huge black balloons (by Thomas Zipp) use up all the available airspace between floor and ceiling in one room. It takes Andro Wekua 170 panels of glazed ceramic to summon a crude sunset, cinema-scale, in another. I liked Max Frisinger’s enormous vitrines crammed with contemporary junk – a world of consumer goods artfully assembled so that they almost seem to have a meaning at which one guesses, nose pressed against the glass, becoming a window-shopper in turn – but less is indeed more, for one vitrine was enough.

Junk predominates as both material and metaphor. Many of these artists, especially those born in the 1970s, belong to what’s been described as the post-po-mo generation, wandering about in an age of vacuity and defeat, making work (this is the spin) that defies the ghosts of 20th-century German culture.

And there is resistance here, to be sure. André Butzer certainly doesn’t want to be liked at all. His monumental canvases, with their scribbly allusions to German and American pop culture, violently worked in garish impasto, are an all-out affront. A Halloween mask, a bit of wonky ab-ex: a canvas can look nearly abstract but still have “Hitler-Cornflakes” lettered up the edge so there is no escaping the sly sententiousness of his work.

Ida Ekblad literally works with junk: bent, flattened or embedded in concrete and upended to resemble a slab of pavement displayed like a picture on the wall. She doodles in scrap metal, sculpts in any old iron. One rusting form rises in twists and turns, parodying early modernism, as it seems, but then she caps the joke with a dirty towel dangling bathetically from the top.

The art in Gesamtkunstwerk is ostentatiously handmade. Anselm Kiefer’s gray canvases are pastiched (by Butzer) in mocking fingerpaint. Huge collages are laboriously assembled (by Kirstine Roepstorff) from scraps and glitter. Alexandra Bircken builds shelters from branches draped with old rags, in the tradition of Isa Genzken (ex-spouse of Gerhard Richter).

Genzken (born 1948) is something of a mother figure here. A whole gallery is devoted to her junk towers, teetering columns of old shoes, fake flowers, battered toys and old master reproductions. Some people find these melancholy, others comical; to me they are deliberately evasive. There are other senior Germans on show – Georg Herold, for instance, represented by two stick-figure odalisques that ingeniously combine drawing and sculpture – but Genzken is the presiding influence, with her lo-fi gaffer-taped aesthetic.

And this is a problem with Saatchi’s nation-based shows. No matter how superbly installed – and even the weakest piece looks briefly plausible here – the art hasn’t the space to speak on its own terms. Similarities, as opposed to singularities, emerge.

Clearly this is not a definitive cross-section of contemporary German art. It excludes the biggest names – Anselm Kiefer, Thomas Schütte, Andreas Gursky, Thomas Scheibitz, Neo Rauch, all shown by Saatchi years ago – in favour of new blood. But even then it represents something quite particular – namely Saatchi’s own tastes, which have in the past tended to the slick, the epigrammatic, the gimmicky and the novel; above all, the immediately recognisable look.

So you have the Tobias twins, Gert and Uwe, painting quirky discs and biomorphs in bright colours – a bit Klee, a bit Miró – except that they turn out to be woodcuts applied to mural-length canvases. Or Jeppe Hein’s mirror painting that vibrates at your approach. Or the large-scale model that features in almost all Saatchi shows – in this case Zhivago Duncan’s post-apocalyptic mountain range through which tiny trains, planes and automobiles chug and whirl on miniature tracks; toy art, fun to gawp at.

The work here is stuff, and treated like stuff. You pick your way through the assortment – geopolitics, gender politics, crass comedy – in a spirit of curiosity. So this is what they are doing in Stuttgart or New York (some of the German artists live abroad; some of the German-based artists are American or Scandinavian).

Everything slides out of mind as you stroll, leaving one thing behind for the next, homing in on something, side-stepping something else. It is the gallery equivalent of shopping.

And if Gesamtkunstwerk represents anything at all, it is the market: contemporary art that is still emerging in the commercial sector, passing through the biennale phase or, with luck, on its way to a private collection or museum. This show may or may not help it on its way, who knows. But it is unlikely to come to rest with Charles Saatchi.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.