Art can take you anywhere. At the Dulwich Picture Gallery you are on the shores of a frozen lake at twilight as the ice cracks purple in the gloaming. You are there as the maple trees shed their crimson beauty on the forest floor. You are there as the mountain rises, fir by countless fir, to a peak reflected in the river below. It could be any century, any northern wilderness in late autumn.

Or so the scenes might suggest. But the paintings tell otherwise, being very evidently works of the early 20th century. At first sight, the gorgeous landscapes in Painting Canada show the influence of Hodler, Munch, Böcklin, a touch of Van Gogh, a trace of turn-of-the-century Swedish painting to the extent that one might be looking at northern Europe. But something tugs at the eye, beyond the maple-leaf scarlet, vermilion and gold. It is the constant sense of expanding distance, of each picture implying something far beyond its confines, namely the vast rolling emptiness of Canada.

Canada is unexplored territory for British museums. If you have never seen anything by Tom Thomson or the Group of Seven it is hardly surprising, since this is the first time their works, considered national treasures over there, have been shown in this country since 1925. Which is no small oversight, given that Thomson is high on the list of Canada’s greatest artists.

Thomson (1877-1917) was a pioneer in both senses. He climbed the peaks and trudged the snowbound wastes of his paintings. An autodidact who worked for the Toronto design firm Grip Ltd, he was an avid student of Van Gogh and Cézanne, his Provence, so to speak, being the 7,650 square kilometres of Algonquin Park.

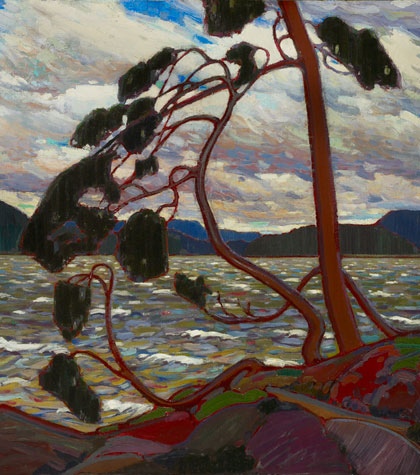

Blue snow burdening the boughs at dusk, wind streaking the inky waters of Canoe Lake, trees flaming up the mountains: nature gave him the colours, but Thomson found a way of imitating nature with his brushstrokes. In his art, the last fragment of ice on the lake melts into liquefying pigment, earth is hard-pressed as iron, sunset burns in crisp golden flakes through the black branches of pine.

In Evening, Canoe Lake, the trunks of winter birch stand ochre, gold and tangerine against an impacted purple sky, solid as ice. Hyphens of auburn and cobalt paint applied horizontally will make a lake; vertically, the tree-clad hillside above it. And trees are everything in this show. They are latticed windows to the sky, and meshes through which bright lakes are glimpsed. They measure the landscape and determine the structure of each painting: trunks in close-up, glades in the middle distance, woods as solid and complex as a rood screen through which tantalising horizons are visible.

And when something skews the geometry – a waterfall, say, or an actual person – the picture is almost always weakened.

Canoe Lake was where Thomson disembarked from the Toronto train. He would stay in the logging village there and canoe the length of the park with his paints. It is also where he disappeared on a summer night in 1917, his body only hauled from the water eight days later. Did he fall from his canoe, was he murdered, why was he so swiftly buried and then exhumed? His death remains a mystery.

The artists of the Group of Seven are to some extent Thomson’s followers. They signed their paintings in humble block capitals, as he did; they attempted the same feat of conveying the wilderness on tiny panels as their friend. And his little oil sketches (21 x 26cm) are a marvel: one looks into them, into their world condensed, rather as into a Samuel Palmer.

But the seven go separate ways, of course. AY Jackson’s Night, Pine Island is a fairytale vision of pinprick stars and midnight clouds, repeated in a pool of turquoise water somewhere in the lonely mountains. JEH MacDonald is more vividly austere, his striations anticipating abstract expressionism. Arthur Lismer’s Cloud Rack is a procession of letter Cs dancing across the violet sky like something out of early Disney.

Each painting spikes a desire for the next – more of this landscape, more of these painters. Though they are certainly not evenly gifted. Lawren Harris – for some reason fetching higher prices than Thomson these days – seems to me to be the least of them, with his stylised peaks, bleached out and accordion-pleated, and strongly reminiscent of Georgia O’Keeffe. He has a whole chilly room to himself.

Sometimes there is a tent, a plough, the odd figure, even in one case a miniature biplane buzzing over the dense forestation, but mostly these are the uninhabited expanses of Canada at the start of the last century. It is a land of green northern lights and pink spring snow, of lightning-struck evergreens and canoes adrift on glassy water reflecting the red haze of maples. The strange beauty of the landscape is transporting.

The pictures brought back by these passionate painters show us these remote and unseen places, these sights we might never see. They also carry knowledge of what the world looks like when we are not there. Painting Canada is one of those shows that does more than transplant the viewer, for a while at least. It feeds the imagination.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.