Ralph Rugoff: The title of this exhibition is Love is What You Want. Where did you first hear that phrase?

Tracey Emin: I probably first heard it in general conversation, but where it first really mattered to me was with Marc Bolan’s song ‘Planet Queen’, which went ‘Love is what you want / flying saucer take me away / give me your daughter.’

Did those words strike a personal chord with you?

I thought it was really honest and brilliant, and it made me think how love is what I really wanted. Then the ‘flying saucer take me away’ line made me think, yes,

I want to be whisked away, I want to be taken to oblivion and caught up in some passionate whirl. But I’m not.

In a far cry from that kind of fantasy, your exhibition at the Hayward opens with

a sculpture of a derelict, pier-like structure with a small shack perched on the end of it (Knowing My Enemy, 2002, pp. 42–43). Like many of your larger sculptures, it is constructed in a provisional and precarious fashion, almost to the point that you’re not quite sure how long it will remain standing up.

It’s not a set for a play or a corporate product. It didn’t come out of a mould. There’s something else going on with it. It would look utterly desolate if it weren’t for some homemade curtains that appear in the hut’s window.

You can imagine coming across it on a beach somewhere, and finding there’s no one there, but then, just as you’re walking away, you turn back and you see the curtains move.

So it evokes that sense of a missing presence.

I’ve often tried to make a place in my work where I think my dad would be happy. Or where I would be happy. And one of my dad’s dreams was to live in a little hut on the beach with a corrugated-iron roof, and to hear the sounds of the rain coming down on the roof and the sea lapping up. And this is a dream that

I shared with him. There’s also a text that goes with the piece that my dad wrote about giving up alcohol. He wrote a story to give me in order to try and get me to cut down on drinking.

In the past you have talked about the literal character of much of your work, but Knowing My Enemy seems more metaphorical.

The really big sculptures are metaphorical. The bigger they are, the more metaphorical they are. So I’ve made works like the helter-skelter [Self-Portrait, 2000] and the rollercoaster [It’s Not the Way I Want To Die, 2005] that aren’t exactly literal.

What about a sculpture in the exhibition like Salem ,a construction made with reclaimed timber and neon that suggests an abstract bonfire?

Salem in Massachusetts is where all the witches were killed at the end of the

seventeenth century, of course, and that piece came out of some weird idea about persecution and feeling hurt and damaged, and being on the run.

When you first exhibited Salem in New York, it was shown alongside a group of white fabric works that conjured up fairly innocent or sentimental expressions of desire. In that context, Salem seemed like a dark reminder of how women in history have been punished for acting on, or even simply expressing, sexual desire.

When I made that sculpture, it seemed to correspond very well with what was going on in my life. I felt like I was being punished at that time.

The Hayward exhibition includes a related sculpture from that New York show, Sleeping with You (2005, p. 227), which also mixes used timber and neon.

It’s one of my favourite sculptures, even if most people don’t understand it.

To me, it’s obvious. You have this neon line on the wall that looks like a lightning bolt you might see streaking over the desert, and then you’ve got what I call the ‘cat spirals’, which I made so that my cat Dockett could climb up and look out the window. I had them in my studio for ages, just leaning up against a wall or in a corner, and I really liked the way they were nestling together and depending on each other.

So the sculpture is built around this tension between these cosy, nesting spirals and this wild squiggly line that unfurls above them.

Yes, it’s like the way sleeping with someone can be really difficult. It has its cosy bits and its haphazard streaks of lightning. It has the snoring, the argument, the tension, the sweat, the smells

Do you see it as a kind of counterpoint to Salem?

Yes, definitely. It’s like Sleeping with You is female and Salem is male, this vertical whoosh.

One section of the exhibition brings together works from the past five or six years, like Salem and Sleeping with You, that use a very pale, muted palette. Compared with the louder tones of some of your earlier work, these more recent pieces seem to convey a hushed quality, as if all that emotional turbulence from the past had been sublimated.

Everything got so colourful at one point, I was making myself feel sick. All the coloured neons and blankets – it was a lot to be carrying around in my head all the time. I think what happened was that I wanted to make more mature-looking work. It’s still totally immature and emotional; it just looks slightly more palatable.

So these works have a slightly deceptive quality, since when you first see them from across a room, they evince a delicate, almost ethereal presence.

My Bed was also like that. When you saw the bed from a distance in the gallery, you’d think, ‘Oh, look at that, it’s so gentle.’ It was only when you got up close that you realised how disgusting it was.

Perhaps the most innocent-seeming piece in this group of works is also the largest: a giant white neon rose . Despite its size, it calls to mind a quickly drawn sketch.

From afar it might just look like a big, abstract web. Actually, it’s a rose on my bottom. What was brilliant was when I did a drawing of it, I wasn’t trying to do a drawing of my tattoo – I was just doodling but with monoprints. Some of my neons have that kind of casualness. They are like notes that someone would leave on a table, like, ‘I’ve gone to get some teabags – be back soon.’

Much of your work, in fact, seems to derive from very intimate gestures and to relate in some way to your drawing. In many ways, drawing has been your mainstay as an artist.

I’ve probably made about 7,000 drawings over the past 20 years.

Many of them include words, which are written with the same kind of jittery line as you use for drawing figures.

They look kind of psychotic, don’t they?

I think it was Will Self who aptly described them as a cross between Egon Schiele and Dennis Nilsen.

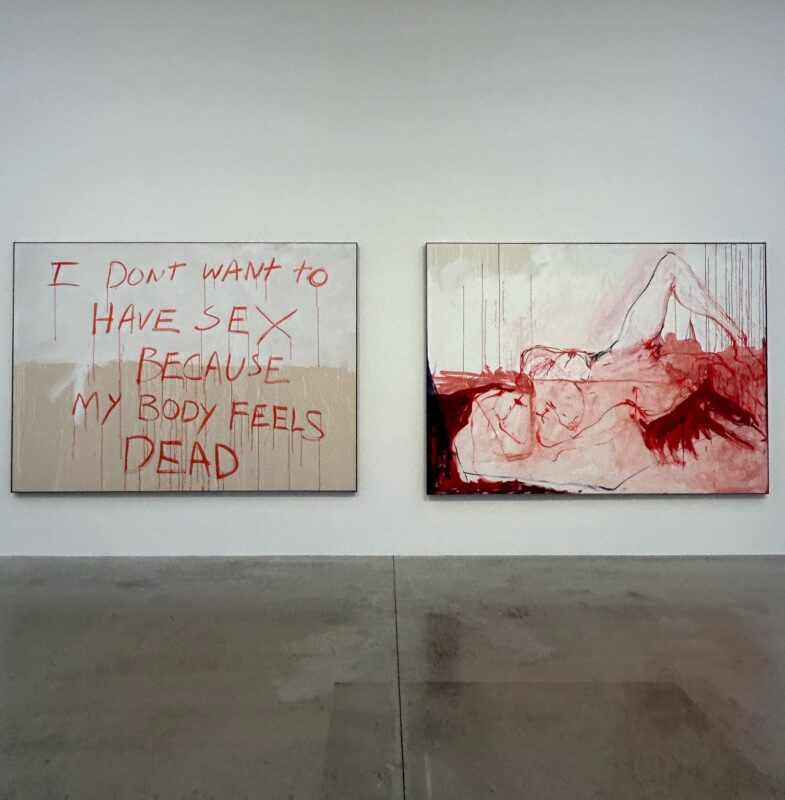

One of the primary images that recurs in your drawings is thatof a female figure whose legs are spread wide open. Why is that such a resonant image for you?

Because as women, we’re told to sit with our legs crossed. When you’re little, you might talk about your fanny or whatever, but you never talk about your hole. Little girls never say, ‘I’ve got a hole.’ You’re not allowed to. There’s no room for that hole. It doesn’t exist until it’s being used, basically.

You have developed several distinct variations of this figure over the years, each evoking different feelings…

Some of my drawings of women with their legs open show girls that are obviously quite shell-shocked, like in the Something Terrible series. Then there are figures who appear a lot younger and more nubile; and more recently I’ve made drawings of figures who are much older, much wiser. Then there are all the abortion drawings where the woman’s legs are being held apart by those calliper things. Twenty years ago if you went to a family-planning clinic, your legs were put in these weird things and it was really cold and mechanical and horrible.

I have all these memories of myself in those situations as well, which I draw.

And do you find that there are still aspects of those memories that you want to revisit and re-engage?

When I re-create things again and again, it’s not because I want to make the same drawing; it’s because I want to work with the same memory. When you’re twenty, you look back at things that happened to you when you were ten.

But then you have a very different attitude looking back at them when you’re nearly fifty.

Another version of the figure with splayed legs appears in your animation Those who suffer love , which shows a woman masturbating.

Many people have said to me, ‘Oh is that you masturbating?’ And I say, ‘I wish it was.’ I’m nearly fifty, and my life isn’t like that any more. With that piece, I was realising that a lot of the fecundity of life was actually over for me. It sounds

a bit silly, but I was sort of trying to re-create or reinvent some kind of female sexuality and to revitalise it. The idea behind that animation also relates to drawing, because drawing’s a solitary act. You do it yourself, using your own line, your own rhythm, your own blood flow, your own vision. So all of that corresponded with the film’s subject. And it was a technical challenge, as I had

to make a few hundred drawings in order to produce 24 seconds of animation. I didn’t use a template. Every single drawing was completely different and that’s why the animation has that fantastic jerky quality – because I didn’t calculate.

It was just naturally the way the line moved.

That kind of off-kilter rhythm animates other types of work that you make, particularly your blankets, which mix up several different aesthetic conventions, including traditional quilt-making. Was your use of cut-out letters in the blankets influenced by punk graphics at all?

No. The punkier-looking letters came out like that because at first I didn’t know what I was doing, so they’re all kind of wonky. Later on, though, I became so graphically proficient it was almost like I’d invented a Tracey typeface in felt,

and that’s why I stopped making blankets for a while. I didn’t want them to get too neat. When I first started, I’d begin sewing a sentence and then realise

I couldn’t get the last word in, and then I’d have to put it in the middle and move everything around it, so it was much more like painting.

The texts in the blankets often conjure a disconcerting mix of voices. Some sound like they might be your voice, while others sound like something someone might have said to you.

Lots of things in the blankets are things that people have said to me. So they are like a kind of conversation. And then you get a blanket like Mad Tracey from Margate. Everyone’s been there , which is made up of my friends’ clothes, so there are lots of different voices in that one.

Another blanket work, Hellter Fucking Skelter , includes the line

‘Burn in hell, you bitch’ and then, striking a very different tone, ‘I find your attitude a little bit negative’.

That’s quite a mad one, but it’s not ‘Helter Skelter’ as in the Manson murders.

It came from the name of a toy shop that used to be on Liverpool Street.

Another blanket in the exhibition features the sombre text ‘I do not expect to be a mother, but I do expect to die alone’, yet its cheery design makes it look like something you might put in a child’s bedroom. That kind of contradiction seems to play an important role in your work. It makes you read the texts in a very different way.

Yeah, it is more powerful because it catches people out, doesn’t it? It’s funny,

my blankets are coveted by a lot of collectors and museum curators, and they’re often attracted to a brightly-coloured one, but then they read what it says and they don’t want it at all.

There is an undercurrent in this show of works that evoke spirituality in one way or another. It may surprise many people, but you have said that you make more work about God than about sex.

Yeah. But now you’ve counted and you’re going to say it’s not true.

No, but it did make me wonder in which category you would put the painting in the show titled Preying For a Penis .

That’s my own painting and I’ve kept it for years. Originally it was a small figure sort of kneeling and praying, and I thought, ‘God, this is crap’. And so I painted the whole thing out in black, but you could still see the figure coming through, so then I blocked the figure out in white, and then I had this fantastically graphic painting. And where the figure’s praying hands were, it ended up looking like the bulge of a penis. Preying for a penis was like me praying for a really good shag, but also at the same time wishing that I had a penis. It was about this idea of being more than I am, instead of feeling less than I am.

Another work in the show that draws an explicit analogy between sex and spirituality is the blanket work Automatic Orgasm , in which you have sewn the words ‘Come unto me’ over an image of a cross.

‘Come unto me’ was what Jesus said, and it also is like the idea of coming, isn’t it? Come onto me, come into me, come be me, share me, eat me, drink me. I’m not religious, but to my mind Jesus died on the cross to transfer his love. And when making love is really amazing, just like mind-blowingly, extraordinarily fantastic, I’ve always thought that you sort of lose your mind. I once said, ‘I feel like

I’m being crucified.’ And then I thought, ‘No I don’t, I feel like I am the cross.’

That’s what that blanket’s about.

In works like these you often bring together references to experiences that many people see as being opposites or incompatible. One such work is the neon sculpture MY CUNT IS WET WITH FEAR

Some people just don’t understand that neon. They think, ‘How can a cunt be wet with fear?’ But to me it’s obvious. It’s about being so excited that a situation becomes fearful or vice versa; and the idea of being wet with fear, like the idea of being wet before anything happens, is really sexy. It’s not a negative neon. It’s really positive.

Certain critics seem to focus on your engagement with personal trauma and emotional distress, and overlook other elements in your work, including your sense of humour.

A lot of people look at the work and say, ‘There she goes again, moan, moan, moan, moan’, but I’m not like that at all. I use a lot of text in my work, and often people just can’t be bothered to read it.

Rather than trauma, some of your works express a straightforward appreciation of sex, which is surprisingly uncommon in the art world. I can’t think of many other artists who would make a work like your fabric piece Beautiful penis.

Yeah, it’s because we’re all supposed to be above it, aren’t we? The majority of people make art that is about something external to their own existence. They don’t make art that is internal to them. People will make art using their bodies like it was a found object, but it’s not about their experience of their bodies.

Interview excerpted from the exhibition catalogue Tracey Emin: Love is What You Want, available for a special exhibition price of £22.99 when ordered via www.southbankcentre.co.uk and from the Hayward Gallery shop tel: 020 7960 5211 (offer until 29 August, RRP £27.99) Text courtesy Hayward Publications. Not for further distribution.