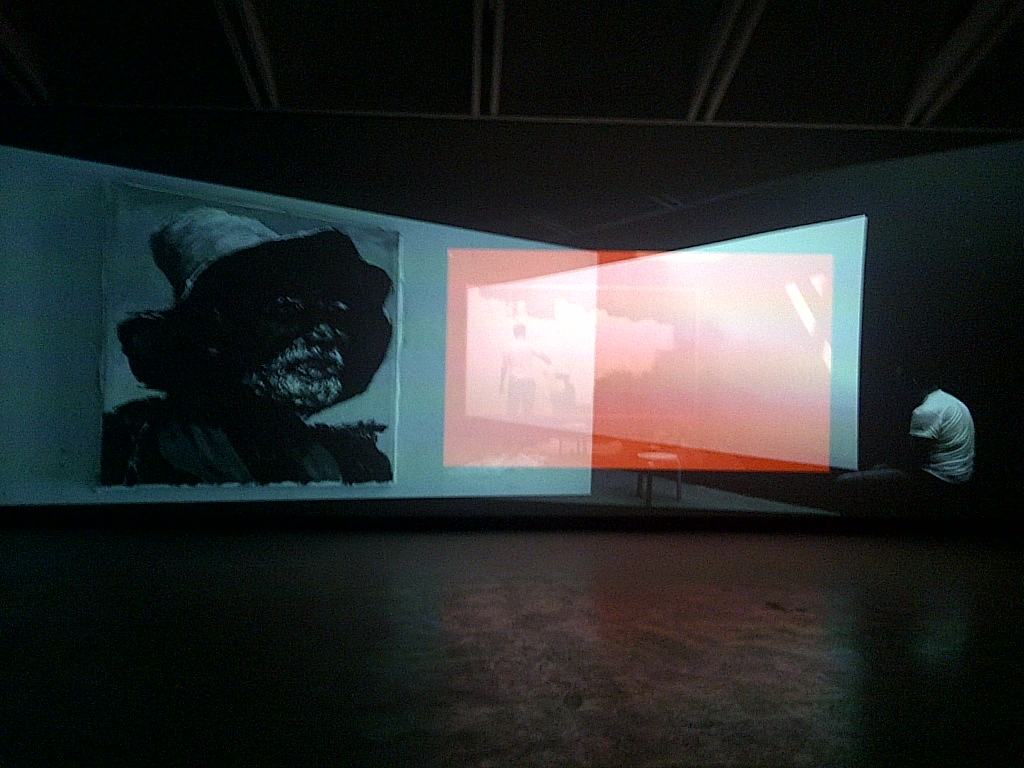

Image: No Idea What this crap is in Biennale Exhibition.

I’ve been trying to avoid reading reviews of the Venice Biennale. What is it about this long-standing, peculiar, art-world institution that makes formerly sensible critics wax rhapsodic about the utter tosh cluttering up some of Venice’s most sumptuous palazzos and pavilions? I’ve spent the past few days thinking about why this might be so. I’ve come to no definitive conclusions, but I suspect that it’s partly because, as with all “exclusive” society events, the critics want to be invited back; but also, I think, it’s a generational thing. The Venice Biennale isn’t a young man’s game: it’s the place where big-name or mid-career artists go to die. A graveyard for those who have already said what they want to say and are now too busy preserving the status quo as opposed to pushing the boat out. It’s all cliché-ridden claptrap, anyway. If I read one more press release or exhibition catalogue where entropy is used as a synonym for chaos, I think I’ll just determine the energy available for useful work in a thermodynamic process. Or scream.

Image:Horrible art beautiful Palazzo Papadopoli

I can’t really compare the quality, or lack thereof, of this year’s Biennale to previous incarnations as this was my first time attending. Most of the people I spoke to in Venice, apart from quixotic broadsheet art critics, shyly agreed that the art was terrible and that this was one of the worst Biennale’s they’d been to. But that was only after they’d had a Spritz or two and I’d broken the critical ice with my braying declarations of loathing.

As far as I can tell, the problems with the Biennale are threefold:

Nationalism is an utterly pointless way to categorise and qualify art. As a card-carrying member of the twenty-first century, I find it laughable that this most important art event still insists on boxing its wares into nationalistic packages. Probably because it’s easier to sell that way…

The contemporary art world as seen through the Biennale has been infected by commercial success. In all of the dozens of exhibitions and pavilions, there were disappointingly few beautiful, intelligent, witty, shiny, clever, ingenious ideas on show. The feeling that all of this work exists because a one Mr Abromavich or his lady love might swan in and buy the whole lot at any minute is pervasive. Where’s the heart? The soul? The skill? The drive to be something more than on the receiving end of a fat paycheck?

The art is utterly dwarfed by the spectacularity of the Giardini pavilions and Venetian palazzos. I see how the peculiarities of the pavilions might serve to challenge and inspire an architect, but it is evident that the artists are totally intimidated by the pavilions as exhibition spaces.

Image: Sweden in the Nordic Pavilion

One of the most depressing sights for me was seeing the anaemic non-entity of a yawn-inducing exhibition of works by Fia Backström and Andreas Eriksson in the glorious Scandi-zen splendour of Sverre Fehn’s Nordic Pavilion. The same was true for spaces outside the Arsenale and Giardini: the Future Generation Art Prize for artists under 35 (it’s a mark of how geriatric the Biennale has become when 35 is considered young) was held at the utterly splendid Palazzo Papadopoli. One of the largest privately-owned palazzo’s on the Grand Canal, it’s owned by descendants of the Papadopolis, a Greek industrial dynasty of whom the Venetians used to say were so wealthy they owned their own wave in the ocean. Whatever that means. Of course the family wealth is long gone, which is probably why they hire it out to the like of the PinchuckArtCentre for six months of the year to stage “forward thinking” art exhibitions for burgeoning young 35-year-olds. The largely unambitious and unimaginative works of “The Future Generation” pale in comparison to the 16th-century magnificence of the palazzo’s ballroom with its massive Murano chandeliers, or the smaller chamber upstairs with its chinoiserie-inspired murals.

Image:Tom Jeffrys-sitting-in-Katerina-Sedas-work-at-Future-Gen-Art-Prize

Having said that, one of the most interesting works I did see in Venice was in the garden outside of Palazzo Papadopoli: a series of embroidered skirt-like circular canvas maps by the Chezch artist Katerina Seda. Seda’s work is rooted in an interesting premise, exploring the damage done to a local community by the arrival of a Hyundai factory. It is supported by demonstrable evidence of much research and engagement with this community she so clearly feels passionate about. The resulting works are charming, beautiful, thoughtful, and provocative. This is what I expected to see a lot more of in Venice.

Image: The Horrible Italian Pavillion

As for the pavilions, Italy’s crowded art-fair style pavilion was, outside of Ikea’s art section, one of the worst displays of art I’ve ever seen; the one and a half hour queue for Mike Nelson’s trumped up Punchdrunk stage set for the British pavilion was simply not worth the wait; and I don’t care what anybody says, Bice Curiger is not courageous or fearless or whatever for displaying three mediocre Tintorettos as the anchors of her ILLUMInations-themed car crash.

Image:Karla Black for Scotland

Karla Black for Scotland was a laughing stock of sour-smelling soap blobs nestled amongst some plain old dirt and paint-dipped cellophane sculptures; Jan Fabre’s Pietas was an unnecessary artistic rape of Michelangelo’s beautiful Pietà (though the gold floor and grey slippers were fun – why not just leave it at that?); Steven Shearer’s stuck in the 1970s figurative paintings for the Canadian pavilion were shockingly ugly; the Dutch pavilion 1:1 scale theatre was a million times more interesting as a scaled-down pop up book than at full size; and Wolfgang Joop’s childishly idiotic sculptures of cherubs and chimps in Eternal Love at Palazzo Bemba may have been one of the worst things I’ve seen in years, let alone at this Biennale.

Image: Wolfgang-Joops-Eternal-Love

So, was it all just a monumental waste of time? Well, no, I suppose. It’s nice to get angry about crap art. It reminds me why I do what I do, why I love the good and loathe the bad; it’s nice to know that I’m still passionate about what really matters. The bad makes the good sweeter, brighter, more essential than ever. And despite all my ranting about the bad, there was the good, too. If one ignores the bizarre press speak surrounding the objects, Yang Maoyuan’s mysterious little pots spread about the Chinese pavilion like replicating viral cells were very good; as was Vesa-Pekka Rannikko’s subtle and hypnotic video piece for the Finish pavilion.

Image:Chinese Pavilion

Image:And all structures are unstable by Vesa-Pekka-Rannikko for Finland

Image:Elizabeth Hoak Doering for Cyprus

Marianna Christofides and Elizabeth Hoak-Doering for Cyprus was another of my favourite pavilions: Elizabeth’s DIY kinetic art drawings were whimsical but provocative, and Marianna’s meticulous collection of photographic and topographic views of Cypriot history was by far and away the best use of archival materials (a technique used by every other artist at this Biennale). Kristaps Gelzis’s contemporary landscape black-lit paintings for Latvia were interesting, but not quite there yet; while back in the Giardini, Markus Schinwald’s pavilion within the Austrian pavilion was sensational, and a wonderful way to avoid his not so good video pieces.

Image:overpainted found painting by Markus Schinwald for Austria

Image:Markus Schinwald structure in Austrian Pavilion

Of all the Biennale’s many pavilions, I never thought the Israeli would be the one to win my heart, but I loved Sigalit Landau’s complex, multi faceted exploration of the geopolitical history of the Dead Sea. Landau tells a new story about a part of the world where, as outsiders looking in, we think we know so much but clearly know very little. Her proposal to build a salt bridge over the Dead Sea to connect Israel and Jordan isn’t described by the expected plans or conceptual drawings, but by a 12 channel sound installation of a series of meetings with politicians and ministers in both countries about the feasibility of constructing such a structure. There are few things that give me greater thrill than works of art with political power without being obviously in your face political. Beauty has political power too.

Image: Stills from Salted Lake by Sigalit Landau for Israel

Alas, most reviews I’ve read appear far more interested in the Geoff Dyer Venice Biennale: parties, parties, parties. Most people I met name checked Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi, a book which I’m not ashamed to say I’ve never read. I started to think that perhaps this is why the Biennale is so devoid of craft, wit, and merit. How did we arrive at an art world where it’s unfashionable to say that you came to the opening of the Biennale to be inspired and to see good art, instead of to binge drink and party hop? Death in Venice, indeed. It’s time for the Biennale to go.