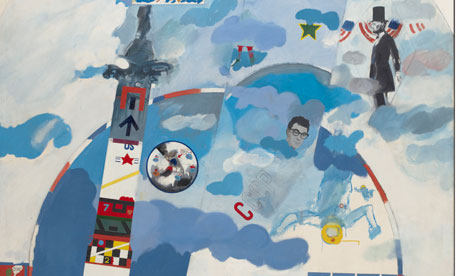

Image: Wonder What My Heroes Think of the Space Race (1962) by Derek Boshier. Photograph: Government Art Collection

Does art have its uses, other than to civilise, enlighten, stimulate, console? Purists would say certainly not. Art has no function whatsoever. But anyone visiting the Whitechapel Gallery, where the notoriously closeted Government Art Collection is being shown in public for the first time in its 113- year history, will discover that this is not the case. Art can be a cunning form of diplomacy.

Take one of Bob and Roberta Smith’s fairground-like signs, brightly painted in chip shop colours and currently hanging in the first tranche of the collection at the Whitechapel (there are several more selections to come). ‘Peas are the New Beans,’ it says, advancing a silly paradox about legumes, but punning on the bean-counting profession as well, at least if you have a mind to spot this.

And plenty have, it appears. When Paul Boateng became chief secretary to the Treasury he hung the painting outside his office, to laugh the waiting accountants and civil servants out of heaven knows what negativity. Apparently it worked every time; full pictorial efficiency.

Sir John Sawers, currently head of MI6, previously at the UN, used to invite hostile nations into his office to dwell upon the beautiful cobalt ground of Claude Heath’s Ben Nevis on Blue – all dots and doodles (Heath draws with his eyes closed) and just shy of figuration. Which was extremely helpful during some particularly heated negotiations on Iran, where the painting was used as a kind of soothing time-out for eyes and mind. “Agreement,” according to Sawers, “was reached an hour later.”

And so it continues: an Anish Kapoor for the high commission in New Delhi to demonstrate how far Britain and India have come together (world-class artist born in Mumbai, resident in London: perfect symbol); Thomas Phillips’s magnificent portrait of Byron posted to the British embassy in Athens, where he remains a hero for taking part in the Greek war of independence; the latest Britart sent to impress smart Parisians, if not to shame their euro-pudding artists. These are works to impress, co-opt and persuade.

So the subtitle of this particular selection, At Work, may be coarse but perfectly apt. It really is as if the artworks are part of the staff, sent out to work as ambassadors for British culture with extra responsibilities during a crisis. And viewed this way – the works at the Whitechapel are put in political context – it no longer seems quite such an affront to the public to be coughing up for a collection it never actually sees.

A good deal has been written about the invisibility of the GAC. I wrote some of it myself, around the time of Blair’s triumphant entry into Downing Street when there was so much press coverage of New Labour receptions, who was in, who was out, and we sought the secrets of the art equivalent: what was displayed (Cool Britannia), and what removed (Old England), from the walls of No 10. For the GAC supplies not just embassies and consulates across five continents but scores of ministerial offices in London as well. Of its 13,500 works, more than two-thirds are displayed at any given time. It is the largest, most widely dispersed collection of British art in the world, and it keeps on moving as governments change and new ministers make their selections.

Hansard is full of questions about how much it drains the public purse, how much of it is mouldering away, how much has been clandestinely sold (none at all). Behind these questions is the lingering grudge that, unless we happen to be ministers, their cronies, or belligerent kids from Jamie’s Dream School granted an audience with the PM, then we will never clap eyes on the mandatory Lowry or the dingy oval view of the Thames by the deservedly neglected William Marlow selected by the Camerons.

What’s ingenious about At Work is that it replicates these selections so that you see the art but also the implicit self-portrait. So Boateng chooses Osmund Caine’s striking group of second world war soldiers from 1940, the whites playing cards in uniform, the blacks separate and naked. Nick Clegg goes for an outsize thermos flask standing alone at a gloomy picnic, surely a post-referendum choice. Ed Vaizey, current culture minister, and Save 6 Music campaigner, continues to show his contemporary credentials by pushing Tory Tracey Emin.

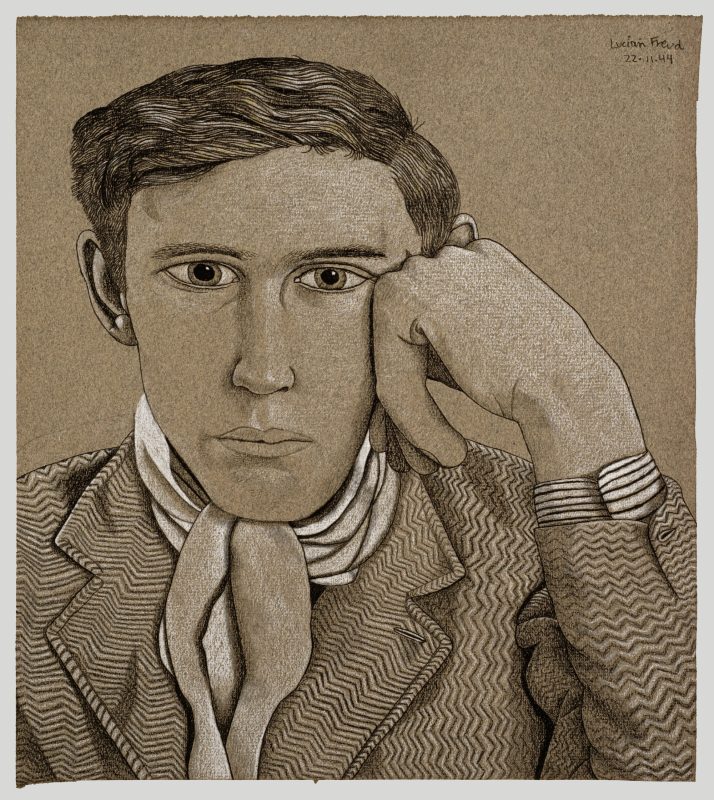

Most piquant of all, Peter Mandelson has chosen a contemporary portrait of Elizabeth I that resembles Margaret Beckett. It’s an awful painting, flesh like Bakelite; but along with a photograph of Lucian Freud painting Elizabeth II, a statue of the artist-diplomat Peter Paul Rubens and one of Cecil Stephenson’s designs for the Festival of Britain, we have two queens, a super-urbane diplomat and a memento of Herbert Morrison, Mandelson’s grandfather (and chief sponsor of the festival), which allows for some self-serving allusions to his own grand projet, the Dome, in the exhibition leaflet.

The choices of Sawers and Dame Anna Pringle, our woman in Moscow, are much stronger as art: Walter Sickert, Heath, some bittersweet space-race Pop by Derek Boshier and Bridget Riley’s beautiful Reflection, bought for the British embassy in Cairo partly because her sheaf of stripes was inspired by the colours of tomb walls in Upper Egypt, but also because the abstraction dovetailed felicitously with Muslim culture.

All these works were purchased on a shoestring budget, just to add to the complex GAC criteria: works must be cheaply acquired, they must act as an extension of the diplomatic service and fit with all sorts of unusual environments. The result is a most quirky collection that has no major Bacon, Hockney, Sutherland or Freud, no Turner, no Constable landscapes, few museum stereotypes. But which is rich instead in great works by Sickert, Joan Eardley and Paul Nash.

That eccentricity went out with New Labour and the hyping of Britart, which is extensively represented in the GAC. This is not reflected in At Work, though one sees how successfully the Emins and Michael Landys have crossed the floor, because so much of the recent art is commissioned to be site-specific.

What you do see at the Whitechapel is just how fine a face the collection gives to Britain at home and abroad, from Edward Burra’s satirical drawings to Bridget Riley. Of course, there is no need to put good art on the walls of our government buildings. But what this first show reveals is just how civilised it looks as our national image instead of a flag or a framed photo of the latest dictator.

‘At Work’ is at the Whitechapel until 4 September, with further GAC selections then running until September 2012, then at Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery followed by Ulster Museum in late 2012-13

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.