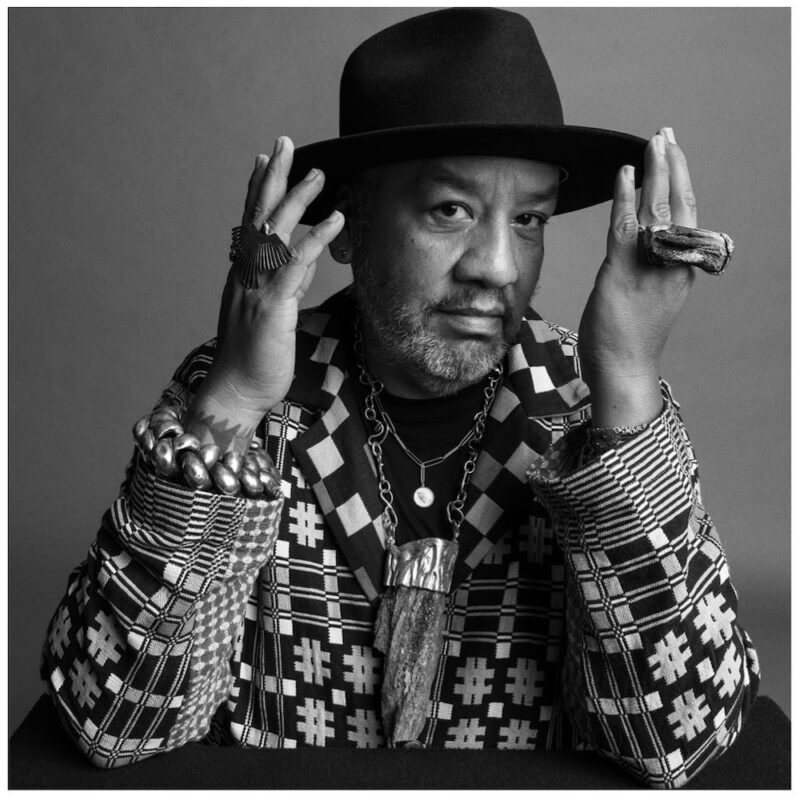

Image:© Subodh Gupta. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth Photo Stephan Wyckoff

2nd February – 8th May 2011

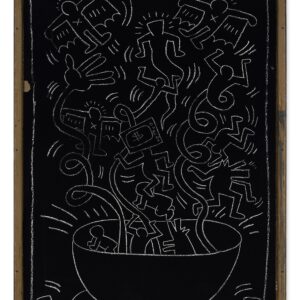

Visitors to Piccadilly’s Southwood Gardens will encounter Mona Lisa, though not as they know her. The most famous and enigmatic personality in the history of Western art has undergone a double makeover: Da Vinci’s muse wears a moustache and goatee — courtesy of Marcel Duchamp’s infamous ‘L.H.O.O.Q.’ of 1919 — and she has increased in scale, becoming a largerthan- life sized sculpture realised in black bronze.

This transformation is the work of Indian artist Subodh Gupta and is both a homage, as well as the beginning of a dialogue, inserting Gupta

into an imaginary conversation between the heavyweights of art history.

Gupta has long explored the effects of cultural translation and dislocation through his work, most famously using Indian kitchen utensils such as tiffins and thalis to demonstrate art’s ability to transcend cultural and economic boundaries. ‘Et tu, Duchamp?’, made only a few years after he first encountered ‘L.H.O.O.Q.’ at Tate Modern, marks a shift in Gupta’s approach towards a direct engagement with works from art history.

Subodh Gupta was born in 1964 in Khagaul, Bihar, India. His recent solo exhibitions include: ‘Take off your shoes and wash your hands’, Tramway, Glasgow (2010); and ‘Subodh Gupta. Faith Matters’, PinchukArtCentre, Kiev, Ukraine (2010). In February 2011, Gupta will have a major solo exhibition at Sara Hildén Art Museum, Tampere, Finland, and his work will be featured in the group exhibition, ‘Paris—

Delhi—Bombay’ at Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France, opening in May 2011.

An appropriation of an appropriation, ‘Et tu, Duchamp?’ speaks of Gupta’s excitement in first encountering Conceptual art and comprehending its power. ‘When I saw Duchamp’s drawing of the moustache on the Mona Lisa postcard,’ he has commented, ‘I was thrilled by this simple thing … Duchamp is a distant figure, but his art is out there in the world, and many artists have reacted to his work’. The sculpture takes Duchamp’s irreverent gesture and monumentalises it – the size, material and solidity of Gupta’s version referencing the artistic qualities that Duchamp did so much to dispel. In making the icon his own, Gupta has taken possession of the language of conceptual art and laid claim to its inheritance.