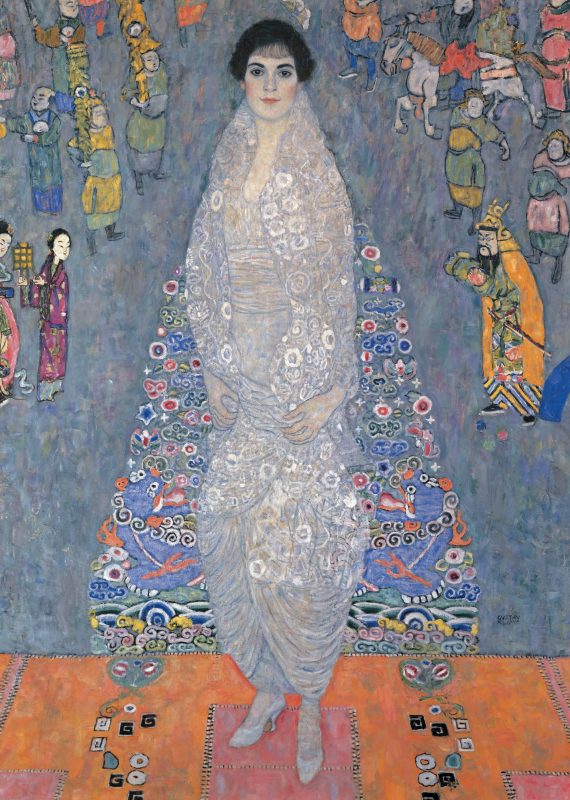

Image:Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862-1918),” Portrait of a Young Woman Reclining”, 1897-1898. Black chalk. 45.5 X 31.5 cm. 2009.57.1 The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

The J. Paul Getty Museum announced today the acquisition of two highly accomplished drawings by Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862-1918), “Portrait of a Young Woman Reclining” and “Two Studies of a Seated Nude with Long Hair” as well as a major pastel by Rosalba Carriera (Italian, 1673-1757), a portrait of Sir James Gray, 2nd Baronet, one of the last works ever completed by one of the greatest pastel painters of the 18th-century.

The Getty has always sought to acquire masterpieces which are representative of an artist’s imagery and style, and also illuminate a particular moment in history. “Gustav Klimt was a leading figure in the Viennese Secessionist movement and his art sums up the strangeness and the greatness of Viennese Modernism at the turn of the century,” said Lee Hendrix, senior curator of drawings. “These two drawings are the first by the artist to enter our collection, and epitomize two quintessential elements of his work: portraiture and erotica. In addition, they represent the achievement of his highest level of abstraction-both in terms of style and content.”

The Getty Museum acquired its first pastel in 1983 and since that time has made building this aspect of the collection a priority. Scott Schaefer, senior curator of paintings, explains that, “With the acquisition of this important portrait by Carriera, all the major pastel painters of the 18th-century are now represented in our collection, and visitors will have the opportunity to see works by master pastellists from the 18th and 19th-century.”

The Klimt drawings and Carriera’s Sir James Gray-which has never been exhibited publicly before-are now on view in the Museum’s South Pavilion Pastel Gallery (S206) at the Getty Center. The works will be displayed alongside Maurice-Quentin de La Tour’s Gabriel Bernard de Rieux (1739-1741), Jean-Étienne Liotard’s “Portrait of Maria Frederike van Reede-Athlone at Seven Years of Age” (1755- 1756), and Odilon Redon’s “Baronne de Domecy” (about 1900).

The three new acquisitions each have their own distinctive frames, specific to the work. Klimt’s “Portrait of a Young Woman” has a contemporary frame designed by the Wiener Werkstätte, a collective of artists and designers with close links to the Secession, while his “Two Studies” is in a facsimile of a frame designed by Klimt himself-both exemplifying his commitment to the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). Carriera’s Sir James Gray retains its florid English Rococo period frame, made for it when it arrived in London.

Klimt’s Portrait and Two Studies

Born in Vienna in 1862, Klimt entered the artistic scene during the building of the Ringstrasse and the rise of a wealthy, largely Jewish, merchant class. With his brothers, he received many early commissions, including the decoration of the staircases of the Vienna Burgtheater, and rose to acclaim rather quickly. With 18 other artists, he formed the Vienna Secession in 1897, and was named the first president of the avant-garde movement. This marked an important period in Klimt’s life and artistic development, as he left behind academic realism and came under the influence of Symbolism.

His “Portrait of a Young Woman Reclining” (1897-98) marks the moment when he invented the erotic dream-state style for which he is revered. In this sensitive portrait, a young woman-her face haloed by a cloud of hair-reclines on a chaise longue and gazes languidly at the viewer. In contrast to the high degree of finish in his rendering of the head, Klimt treated the sitter’s clothing and the back of the chair in a looser, more summary manner, highlighting the emotional connection between sitter and artist. The highly finished quality of the drawing and the absence of a related painting indicate that this is an independent portrait. The young woman bears a noticeable resemblance to Sonja Knips, a Viennese socialite whose portrait Klimt painted during the same period. Whether or not the sitter is actually Knips, the erotic connection between the sitter and the artist is palpable.

The erotic nature of Klimt’s work made him a contentious figure in the Secessionist movement; facing accusations of pornography from the very beginning. But it was the erotic obsession with the female form that would define and differentiate Klimt’s art, and that fascination is unreservedly explored in his “Two Studies of a Seated Nude with Long Hair” (1901-02), two highly stylized studies of a nude woman seen from behind, her generous buttocks thrust toward the viewer and her luxuriant hair cascading around her head as if caught by a current of air or water. The fluid, stylized treatment of the model’s body and hair, which verges on abstraction, suggests his enduring identification of women with water-unbounded, immaterial and elusive-a common motif in his work.

The drawing was made via Klimt’s favored (and somewhat unorthodox) working practice: employing a number of nude models to lounge around his studio striking spontaneous poses, which he captured with a few exquisitely economical strokes of chalk or pencil. Many such life studies remained independent works of art, but others inspired paintings. These sketches ultimately served as preparatory drawings for the foreground figure in Klimt’s painting “Goldfish” (1901-02, Kunstmuseum Solothurn, Switzerland); however, Klimt seems to have considered it a work of art in its own right. Not only did he sign it, he also published a reproduction of the right-hand figure in the Vienna Secession periodical Ver Sacrum in 1902; faint red pencil marks-cropping indications for the photographer-frame the figure.

These drawings complement the Getty’s collection of 19th-century master drawings by van Gogh, Seurat, Gauguin, Degas, Rodin, and others as well as 19th-century paintings and sculpture, especially by Symbolists such as Khnopff and Ensor. In addition, the Getty Research Institute (GRI) has extensive holdings of Vienna Secession material including many volumes of Ver Sacrum.

Carriera’s Sir James Gray

Born in Venice in 1673, Carriera’s skill as a painter and pastellist propelled her to considerable artistic success, rivaled by few women at the time. Her work became the gold standard of pastel painting, inspiring and influencing numerous other pastellists, and patrons from all over Europe vied to have their portrait done by her. She began her career painting miniature portraits on small pieces of oval-shaped ivory (intended to adorn the interior of snuff-box lids) and received commissions throughout her life from an international clientele-principally British, French and German travelers. The other principal group of Carriera’s pastels shows young women in the guise of mythological or allegorical personifications; the Getty Museum’s collection of drawings includes a preparatory study for one of these works, “A Muse” (about 1725).

At an early age, Carriera already excelled at portraits in pastel, and was commissioned in 1708 to do a Self-Portrait (Florence, Uffizi) for the Grand Duke Cosimo II de’ Medici’s collection of artists’ self-portraits. Thereafter she received several commissions for state portraits, but the majority of her sitters were young men on their Grand Tour. Though her pastel portraits featured elaborately dressed, elegant sitters, they lacked severity-even the official portraits. With subtly blended colors, minimal markings, and suggestive facial expressions she provided psychological insight to the sitter.

Her talent was recognized broadly and she was elected to the Accademia di San Luca in Rome (in 1705), the Accademia Clementina in Bologna (in 1720), and the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in Paris (in 1721). She had many important patrons including the young Louis XV and the most fashionable ladies of the French court while in Paris; Joseph Smith, the British consul in Venice; Duke Rinaldo d’Este in Modena; Empress Amalia in Vienna; and Frederick Augustus II, Elector of Saxony (King Augustus III of Poland from 1733). As her style matured, Carriera’s portraits became less playful and increasingly austere.

In 1746, the loss of her eyesight put an end to Carriera’s career as a painter-the Getty’s newly acquired “Sir James Gray” is among her final works. The portrait exemplifies the virtuosity of the artist’s technique at its pinnacle: Her deft strokes of the crayon suggest the tactility and texture of a variety of materials, ranging from the soft velvet of the jacket to the fine, almost transparent lace decorating the shirt front and the multiple folds of the “solitaire,” a black silk ribbon tying together the hair at the nape of the neck which later evolved into the bow tie. The flesh tones of the face are rendered with warmth and luminosity, complemented by astutely observed details such as the strands of the sitter’s own chestnut hair emerging from underneath his powdered wig.

In this portrait, Carriera was able to evoke the subject’s character and intelligence because the sitter was a resident of Venice rather than the typically youthful and impatient Grand Tourist wanting their portrait done quickly while breezing through the city. Since Sir James lived in Venice, Carriera almost certainly came to know him well and had the opportunity to study his facial features from life in repeated sittings over an extended period, resulting in a psychological penetration that is virtually unmatched in the artist’s oeuvre.

The sitter, Sir James Gray, was the son of a courtier, who was created first baronet in 1707 and succeeded as second baronet in 1722. Having travelled to France, Italy, Malta, and Portugal, he became a founding member of the Society of Dilettanti (1738) and served as secretary and treasurer to the society until his death. During his time abroad, he diligently nominated distinguished young men he encountered for membership to the society. In 1744, he was appointed secretary to Robert D’Arcy, 4th Earl of Holdernesse, on his mission to Venice. His successful diplomatic service resulted in his promotion to resident in March 1746, and he remained in Venice until August 1752. In 1753 he was appointed to the court of Naples, and was quickly on good terms with the young King Charles VII (later Charles III of Spain). His final posting was Madrid, where he was appointed ambassador in 1767, a rare honor for a commoner, remaining there only until 1769. Sir James died in 1773 and was survived by two illegitimate children (fathered during his time in Naples). His portrait by Carriera remained in the possession of his descendants until last year.