1. When did you start to make art?

From an early age, I enjoyed walking and exploring the peak district, and often collected

interesting bits and pieces I would find. During my A-levels (1990-92) I started

incorporating these found objects in my sculpture. The first work made entirely from

found objects was a “figurative” sculpture of an elderly person. It wasn’t planned, but

inspired by a unusual piece of rhododendron, which was very evocative, though contorted

and arthritic, of a human skeleton, complete with hips, thighs, and spine. The “head” was

a weathered tree root with expressive features and a crown of mossy hair, with bestial

horns poking through. I sat the work on an old Thonet chair, and propped up an

outstretched arm with a walking stick. Although created by accident and intuition, it

resonated with ideas of our resistance to aging and nature. At this point I began to realize

that nature could be an ally in making art.

2. How did you evolve into a professional artist?

In the summer before going to University, I produced a series of environmental artworks;

rather than collecting materials to take home, I decided to work with them where they

were found. They were created without a plan and without tools. I quickly developed an

approach of minimal intervention and humility, of finding ways to relate to the landscape

without spoiling it.

The process of walking and hunting for the right places and objects to work with, of total

immersion in the environment, was a form of meditation; the distinction between

humanity and nature became meaningless, as did the boundary between the work and

the landscape. These experiences allowed me to develop a deeper understanding of both

human and natural creativity.

At this point, I had already decided that I needed no formal training in art, and chose a

degree in mathematics, having briefly flirted with the idea of being an architect. During

my degree, I took an optional Fine Art module, and produced a series of sculptures called

Manifold 1 using copper piping (the sort used in domestic central heating), which explored

the intrinsic geometry of this industrial system. The change from natural to industrial

objects paralleled my move from a rural to an urban environment.

Ultimately I did not want to pursue maths as a career, but nor was I inspired to become a

fine artist. I felt, and still feel, that the art world profits from maintaining a thin veneer of

pseudo intellectualism, which obscures its increasing irrelevance to society. Art has

become a primarily commercial product, relying on alienation and insecurity to promote

desire.

I decided to pursue Design, as a less hubristic way to satisfy both my sculptural and

rational interests. I see no significant distinction between art and design and approach

both with the same mindset. Both are compositions of objects in space. Both are problem

solving, albeit with slightly different problems. Function is just another rule to consider in

the creative process. Design is functional sculpture. Decoration can be thoughtful as well

as beautiful.

Having spent the last 12 years being sidetracked by running a photographic studio (a long

story), Manifold 2 represents my first project as a “professional” artist/designer.

3. What drove you to make art as a professional vocation?

Each work of art modifies the definition of what “Art” is. I am motivated to contribute to

this definition, and to explore the convergence between art and design. To me this

convergence is about showing that art need not be obsessively intellectual and

conceptual, that there should be no hard boundary between the decorative and functional

aspects of our environment, and that this environment can be intellectually stimulating.

However, I would not define myself as a professional artist. I am ambivalent about art;

Whilst compelled to make it, I cannot make the case that it is, in any objective sense,

important, and it will never be the only thing I do. If I thought that art was a suitable

vehicle for political/social/environmental protest, then perhaps I would think differently;

but it isn’t – political art is neither effective politics or effective art. We face too many

problems as a society that must be dealt with directly to be merely an artist.

In more general terms, while specialism in a particular profession is often a source of

innovation, it also leads to a loss of holistic thinking. Through a steady process of

industrialization and globalization, our civilization has become a complex system of

interdependent specialists. The apparent stability of this system has been propped up by

an abundance of oil. As we pass peak oil into energy descent, we may all have to take

increasing responsibility for the products and services we rely on, and become more

generalists than specialists.

Our obsession with career and success can be corollated to both social and environmental

degradation. To create a sustainable and sustaining society, we will need to break this

obsession, and engage in activities that do not involve pay, but that help to rebuild our

social and environmental capital.

4. Explain your inspiration?

Nature and Mathematics are the most important sources of inspiration. Nature, as the

ultimate source of creation, the master builder, the preeminent innovator of form and

function. Mathematics is a highly structured system of thought which strips ideas back to

their underlying axioms or assumptions to see how they work, before developing them to

their logical conclusions. And yet, despite its unassailable logic, it is a highly intuitive and

creative field; Like science, it often uses beauty as a method of detecting, if not proving,

truth.

Many of my ideas are to do with patterns in the geometry of my chosen objects. There

are many variables that come into play with this geometry; rather than producing a single

optimal solution, I prefer to explore in a series how the geometry performs under

repetition and variation.

In a sense my work is about identity. Many artists work is a definitive stamp of their own

identity, their authority over their subject; whereas I employ various strategies to remove

my identity from the artwork; I choose to work with objects that have their own identity,

and which dictate the ways in which they can be composed, such as Treen and Manifold

1. I also impose rules and constraints in order to delegate responsibility, such as with

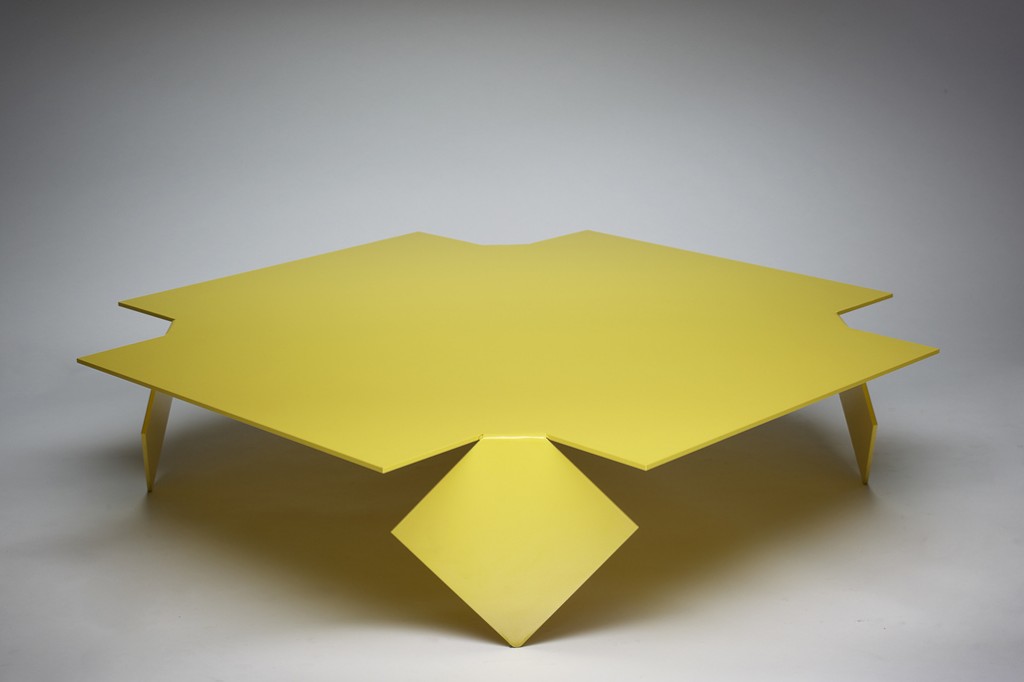

Manifold 2, which restricts the design process to cutting and folding of square sheets. All

my chosen objects are the products of complex systems, whether natural, industrial or

mathematical.

5 In what way does your inspiration transform into ideas?

I have no prescribed method for generating ideas. I am not an industrial product designer,

driven by a need to fulfill, or problem to solve. Nor am I an artist labouring to create a

towering edifice out of his life’s work. Most of my ideas just flash out of nowhere like

quantum particles, with no preamble or process. To me, they are little gifts from the

infinite void of consciousness, whether they come from my own subconscious, or some

Jungian collective consciousness. If there is no thread between any of my future work, it

really does not matter to me; I simply enjoy the novelty of each new idea. In fact, the

more disjointed and random the next idea from the last, the better.

6 From Ideas to production of art – how? And why?

Because my ideas are all about the materials and the method, there is no disconnect

between the idea and production of the work.

7 Could your ideas be portrayed in any other medium? If so which?

For the same reason as above, it would be inappropriate for my ideas to be portrayed in

other mediums.

8. Which artists would you most like to blatantly rip off?

I have no desire to rip off any artist; Art is not, or should not be a competition, rather a

collaborative process where one can build on the work of the past, like science. Having

said that, the artist I would have most like to have been is Marcel Duchamp, whose work

represents the only real discontinuity in art history there has ever been or ever likely to

be. I also covet the work of Jeff Koons, in particular his chrome balloon rabbits, for their

simple wit and general shininess.

9 Why is your art made?

The same reason a musician makes music – because the act of invention and creation is

pleasurable. I am happy to share the results with a wider audience, although I would make

art even if only for myself. If I were marooned alone on a desert island, I would no doubt

continue to make environmental art.

10 What does being an artist mean to you?

I would prefer use the term artist in a wider sense, as someone good at something, rather

than simply a noun for someone who paints or sculpts. This includes music, architecture,

and the rest of the “arts”; I appreciate the work of more musicians, and to a greater level,

than that of fine artists. Music is a more powerful and affective medium than painting or

sculpture, which actually engages directly with the nervous system. Very few works of art

could be stand being looked at for prolonged periods, or repeatedly.

I would also include the sciences. Science isn’t strictly a rational process of extracting

laws from experimental data. It often involves vast leaps of imagination, of creative

thought, which are no different from any artistic impulse. In that sense I would define

being an artist as someone involved in creative thought. That thought can be purely

cerebral, or it can be with paint brush in hand, steering every micro decision. This

creativity can and should be applied to every activity, whether producing art or running a

business. It is about being conscious of one’s actions at all times, avoiding routine, and

adding innovation wherever possible.

Being an artist is about exploring new territory; but the search for newness above all else

has made shock tactics the default setting, and pushed art further and further out on a

limb.

11 Are you happy with your reasons for making art? i.e Are there any trade offs that

make life hard?

I very much enjoy the irrational way in which I am inspired to produce particular ideas;

they are as much a surprise to me as they would be for an audience. Art (in its wider

sense) really needs no explanation or justification. It should be able to simply revel in its

own existence, existing for its own sake, and on its own terms. This is its saving grace,

but also its biggest flaw, in the context of a civilisation unable or unwilling to prevent its

own self destruction.

I expect the randomness of my process, the lack of a connected history or narrative to be

a barrier to becoming a professional artist/designer.

12 When does your art become successful?

Success (or failure) is not really an issue I deal with. I would never judge success by

popularity or commercial metrics, as the reasons for making art are internal. But also, as

my work is not process driven, there is no real opportunity for failure, and thus for

success.

13 What is art?

“the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual

form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their

beauty or emotional power”

I would agree with this dictionary definition, certainly regarding the importance of creative

skill, as well as imagination. I would also endorse the final phrase regarding beauty or

emotional power. These are necessary and sufficient constituents of successful art;

without them a work has failed, regardless of any other factors. I would not want to add

anything to this straight forward and open definition, as this would only place

unnecessary limits on what art can be.

14 How do you start the process of making work?

There is no set process. Some work has involved walking and responding to an

environment, or to composing a set of found objects. Manifold 1 began with making

models out of wire to explore the geometry before moving on to copper. Manifold 2

started with cutting and folding card, and then to CAD, before commissioning steel

fabricators. As both sculptor and designer I am comfortable moving between hands on

craft, CAD and outsourced production.

15 Who prices your work? And how is the price decided upon?

I have yet to decide whether Manifold 2 will be mass produced or limited edition, or sold

via a retail or gallery outlet. Once these decisions have been made, pricing will be

determined by myself and my agent.

16 What is your next; move,project,show etc?

I will be creating tables and other functional pieces from scale models of familiar things,

taken out of context. I have always been fascinated by things out of scale, either larger or

smaller than they should be. They have a strange power to displace my sense of reality,

to create an incomprehensible but palpable shift in perception.

17 What are the pros and cons of the art market?

It seems to me that professional artists are effectively brands, defined by a set of core

values, and other tangible and intangible assets. By collecting Art, people are buying

shares in these brands, which go up and down in value; this demands a process of working

which generates a continuous and connected stream of work, which exhibits just the right

amount of (not too much) novelty. I have no such desire for consistency.

However, whereas the design/retail market judges success on volume of sales, and so

wide appeal, the collectors market has the potential to support greater individuality, and

provides a direct connection to an audience.

21 Who has been the biggest influence on you?

The work of Andy Goldsworthy and Marcel Duchamp were very influential to me as a

young artist; Duchamp for removing any limitations on the creative process, but also

reminding me not to take art seriously. Goldsworthy showed a direct and humble way to

express a connection with, and respect for, nature. Almost as a byproduct he developed a

fairly radical way of producing art.

In the design world, Charles and Ray Eames are the greatest exponents of my favourite

period; they had a great talent across many disciplines, including furniture, art,

architecture and film.

www.anthonyleyland.com