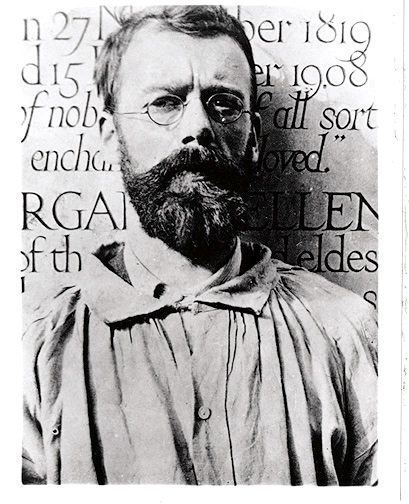

“I have found, as a biographer, that you do not choose your subjects. It is more that they sit in your mind waiting to claim you.” When Fiona MacCarthy wrote this she must have pondered what it was about Eric Gill that made him sit in her mind to start with, now that we know perhaps more than we ever bargained for about some aspects of his life story. With Gill’s work forming part of an upcoming exhibition at the Royal Academy entitled ‘Wild Thing’, and our heightened sensibility through media coverage towards abusive sexual relationships, especially involving children, it seems we are bound to reflect on how artists’ works and lives interact.

From way back artists have been associated with often chaotic and indecorous behaviour. Many of them led complicated sex lives, often less shocking today than they might have been at the time, but with some things we tend to draw the line. For most people even today, and certainly as far legality is concerned, Gill went too far. Just one look at the varied index references in MacCarthy’s biography of Gill provides enough clues. The question is how it affects his work and how we view it.

The curious thing is that the closest most of us ever get to Gill’s work is through the typefaces he designed, ones we see on a daily basis in print, in signing or online. Although not as ubiquitous as a few years ago, Gill Sans is still a common font, even on our computers. A close inspection of the letterforms reveals something that is identifiably modern, but still distinctly classical, referring back to Roman inscriptions from which Gill drew ideas and inspiration. This purity of form is even more pronounced in his Perpetua typeface, the height of good breeding and historic sensitivity. How could a mind so refined and a hand so skilled belong to this other individual?

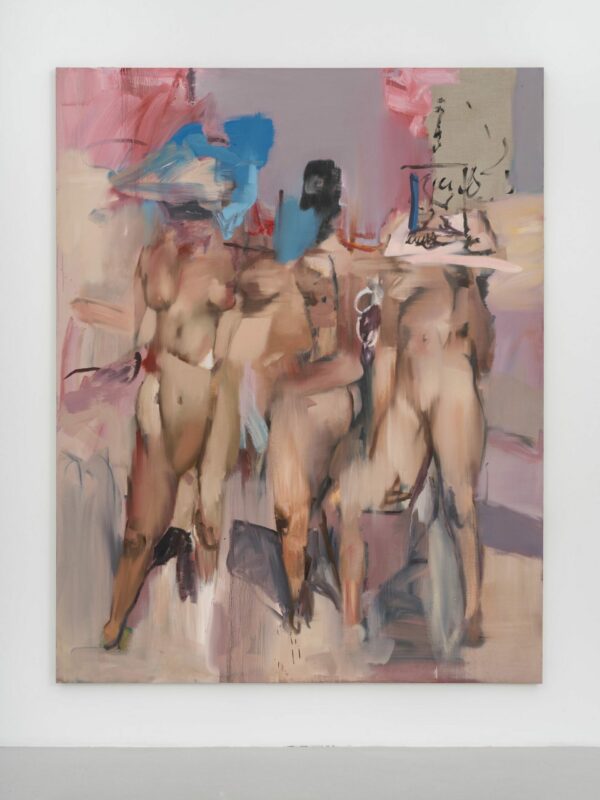

If we look at Gill’s drawings and prints, or even Gill’s infamous relief re-titled Ecstasy (replacing Gill’s own unambiguous title Fucking) we see, or at least I do, a remarkable sensitivity that is more chaste than consciously erotic. Ecstasy takes the human forms and moulds them in an embrace that is touching and intimate. That the models were Gill’s sister (with whom Gill had an incestuous relationship) and her husband does nothing to change our initial reaction.

Undoubtedly some of his private works were salacious, whilst other commissions were deeply religious in tone. One work explicitly uses sex to make a political point. His carving Votes for Women (purchased by the economist John Maynard Keynes) is described by MacCarthy as showing ‘the act of intercourse with woman ascendant, man semi-recumbent.’ In a curious way the political message here could not have been more modern. As MacCarthy comments ‘it is both very pure and very shocking.’

Though full of ambiguity as Gill’s life was, not just sexually and morally, but riven through his writing, his domestic and working relationships and his spiritual preoccupations, his work as an artist and as a designer still stands out with searing clarity. Something it is difficult to argue with.

MacCarthy, F. ‘Mad about sex’ (Guardian 17 October) 2009

‘Wild Thing: Epstein, Gaudier-Brzeska, Gill’ at the Royal Academy 24 October 2009-24 January 2010