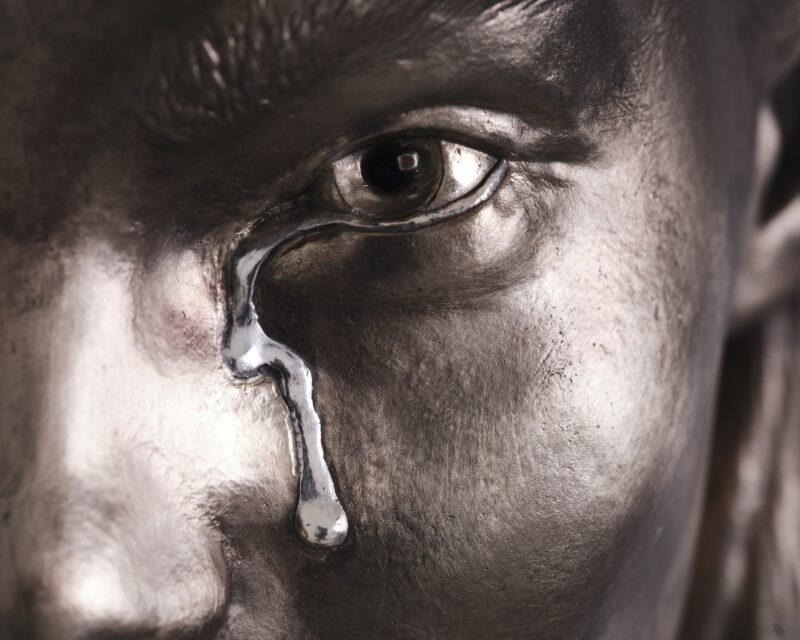

Rent Collection Courtyard, 1974–1978 (original 1965), Test the Quantity of the Grains (Detail)

In conjunction with China’s appearance as Guest of Honour at the 2009 Frankfurt Book Fair, the Schirn will be showing, for the first time ever in the West, the spectacular Chinese sculptural group Rent Collection Courtyard (Chin.: Shouzuyuan). This ensemble of more than 100 life-size figures is among the most important works in modern Chinese art history, and is firmly embedded in China’s collective memory. Created as a site-specific installation in Dayi in 1965 by teachers and graduates of the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute in Chongqing, the group of figures soon became a model artwork of the Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966. Over the following years several variations of the work were made and exhibited throughout China, only one of which survives today. This is a mobile travelling version made in 1974–78 from copper-plated fibreglass at great expense, and is located in the art museum of the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute in Chongqing, central China. In a dramatic sequence of scenes, which unites traditional Chinese, Soviet, and Western stylistic elements, the ensemble of figures depicts the merciless exploitation of the peasants by a rich, pre-Communist landowner. As the Cultural Revolution largely fades from people’s memories, young Chinese artists have repeatedly returned to the work, and it has figured in many current discussions on contemporary art in China.

The Rent Collection Courtyard is a unique ensemble of a total of 114 life-size clay sculptures. It was created as a site-specific installation in 1965 in the former property of the notorious feudal landowner, Liu Wencai (1881–1949), which had been converted into a memorial museum in the Dayi District of the Chinese Province of Sichuan. Teachers and graduates of the sculpture class at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute in Chongqing were commissioned by the Province’s Ministry of Culture to create a representative work in Dayi to memorialise the exploitation of tenant farmers by the local landowner in the period before the Communist Party’s victory in 1949. In collaboration with local folk artists and in the space of a few months, the working group developed a monumental narrative composition. In seven scenes, some based on reports of real events, such as Bringing the rent, Asking too much, and Flames of anger, the lives of the peasant population during the Chinese Republic (1911–49) is depicted. Tired, oppressed peasants drag sacks full of grain, or beg desperately for a delay on their rent demand, while the lying henchmen of the landowner exact payment in a brutal way, tearing families apart and imprisoning people behind bars. The depiction ends with the uprising of the enraged peasants as an indication of their readiness for class warfare.

Like all the art production of the new Communist China, the project fell under the unambiguous hegemony of the political. A theoretical basis was given by Mao Zedong’s Speech on literature and art at Yan’an in 1942. In it he formulated his concept of a revolutionary Chinese art for the people. Appealing to Marxist art theory, Mao demanded a politically oriented art in the service of the masses, with the task of depicting and celebrating the achievements of the proletariat. To fulfil these demands, artists should live alongside workers, peasants and soldiers, and learn from them. In 1965, the “Speeches” were still considered to be definitive. But although created within a clearly defined ideological framework, the Rent Collection Courtyard is something new in the history of Chinese art: the group of sculptures unites different lines of artistic tradition in an unprecedented way. Stylistic elements of Classical and social-realistic European sculpture combine with the formal language of Soviet-inspired Socialist realism. Furthermore, at that time the Chongqing Academy reflected on a particular form of the Chinese sculptural tradition: Buddhist stonemasonry in the temple grotto of Dazu during the Song Dynasty (960–1279). Equally significant was an intensive exchange between the artists and the local rural population, who were involved not just as an authentic source and object of study, but also as a critical corrective in the creative process.

In addition to its impressive scope, it was doubtless the installation’s presumed authenticity – underscored through being furnished with real tools and equipment from the farmers’ daily life – and the immediacy of its expressive power, that justified its sensational success. The opening was followed by a storm of visitors, and according to reports there were repeated outbreaks of highly emotional scenes. Some of the visitor groups were organised, but many people simply felt the need to see the figures, often entailing long journeys on foot. Because of the overwhelming response, of both the rural population and high-ranking officials, another exhibition was held in 1965 in Peking with copies of 40 of the 114 figures, which was seen by half a million people in three months. The first articles appeared in the press while work was still ongoing in Dayi, and in 1966 a 35-minute documentary and a gramophone record were released. Within a very short time, the Rent Collection Courtyard was famous throughout China.

The wide-ranging success story of the work is inseparably linked to the beginning of the Chinese Cultural Revolution in spring 1966, when at a stroke the political and cultural climate in the country was radicalised. At the instigation of Mao Zedong’s wife Jiang Qing, who was appointed to the newly founded Central Committee of the Cultural Revolution and entrusted with direct control over culture, the Rent Collection Courtyard was declared a compulsory model artwork for the orientation of visual artists. At the same time, however, there was criticism of the ensemble, since it did not fully accord with the newly formulated guidelines of art production – which expressly required a focus on positive role models and heroic characters. Thus in the subsequent years numerous variations of the sculptural group were produced and exhibited throughout the country, but with a drastically modified final sequence that was in line with the new ideological demands. It was accompanied by intensive political text production and propaganda.

Through richly illustrated catalogues, which were published in numerous languages and even in the West, the work was soon able to arouse interest outside China. Not least in Germany: there, in the context of the turmoil of 1968 and after, it was received as an outstanding example of authentic revolutionary art. There were repeated attempts to exhibit the work in the West. For example, Harald Szeemann, as curator of documenta 5, tried in 1972 to bring one of the sets of figures to Kassel, to show it to the international art world; but this proved impossible for political and financial reasons. Later, in 1999, together with the Chinese artist Cai Guo-Ciang, who lived in the USA, he planned to show the sculptural group at the Venice Biennale. When this plan also failed, Cai instead realised a work that referred back to the Rent Collection Courtyard, and with which he won the Golden Lion. This sparked a conflict in China over the copyright to the work, which became the starting point for a wide-ranging debate about the position of the artist and the freedom of art in contemporary China, and about the relationship of the Chinese and Western art worlds. Since then, the Rent Collection Courtyard has also inspired other young artists to produce new versions.

The exhibition “Art for the Millions. 100 Sculptures from the Mao Era” focuses on a period in Chinese art that has so far received almost no critical examination, within or outside China. The importance of the visual art of the Mao era – and in particular the period of the Chinese Cultural Revolution – should not be underestimated. Its effect on the development of 20th-century Chinese art, as well as on our understanding of its significance, is enormous. With this in mind, the exhibition uses an outstanding work – and its eventful and moving history from 1965 to today – to open the discussion and to contribute to exploring this largely untreated topic.