Tuesday 2 June – Saturday 12 September 2009

La Tauromaquia, a series of one hundred small drawings celebrating the art and ritual of bullfighting by José María Cano (b. Madrid 1959), go on display in an exhibition of the same name at Riflemaker, from 2 June.

José María Cano (b. Madrid 1959) is internationally known for his ongoing series of paintings, The Wall Street 100, one hundred life-size portraits made from paraffin wax. Among Cano’s subjects are Francois Pinault, Alan Greenspan, Barack Obama and Bernard Madoff, each selected for their perceived level of global economic power.

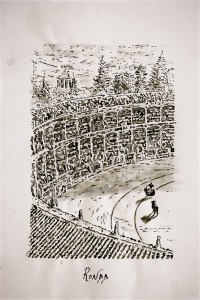

In contrast to the grand themes of power and money addressed by Cano in The Wall Street 100, the delicate ink on paper drawings that make up La Tauromaquia are intimate and small. They depict matadors, picadors, bulls and the arena in the preparation for and performance of ‘la corrida’ while conveying the Act of Faith and pageantry involved.

Cano has spent time watching bullfights and befriended many of those involved in the event, from famous toreros to breeders of the Spanish ‘toro bravo’. He follows Goya, Picasso, Lorca, Hemmingway and Orson Welles who are among those writers and artists inspired by the bullfight, fascinated by the ceremony of the event, rather than the controversy that surrounds it.

Similarly it is the dramatic dance between man and beast and the psychological relationship that develops between them on which Cano focuses. In a work entitled ‘If you want to know what will happen, look at their eyes before the bullfight’, the bullfighters are lined up, preparing for the fight, depicted in a state of deep contemplation prior to entering the ring; whilst in ‘José Tomás in Madrid’ we share in the crowd’s adoration of the torero.

‘I think I have a right to speak about bullfighting, because I was, for a while, I don’t quite know why, but I was, an aspiring bullfighter. For me a bullfighter is an actor facing real things. I spent a good deal of time around the ranches where fighting bulls are raised. But don’t be worried, you don’t have to approve of bullfights, I don’t ask you to, and I certainly wouldn’t dream of defending the spectacle. I was personally fascinated by the spectacle as a ‘whole’ but whatever your attitude may be, remember that you can plug for the bull and there will be no hard feelings about it.’ Orson Welles, 1955

The ritual of bullfighting has ancient roots and thus references to it have made their way into language and customs. The words Europe (Europa) and Italy have bovine roots and Cano’s series Verónicas – the most frequently used cape ‘manoeuvre’ – is named after Saint Veronica who held out a cloth to Christ on his way to the crucifixion. Despite opposition to the spectacle, bullfighting is still integral to Spanish society – almost a million people watch bullfights in Spain each year – and it is also practised in parts of France, Portugal and many Latin American countries.

In 1994 Cano composed an opera – Luna – with a Spanish theme in which Placido Domingo and Renée Fleming take the lead roles. For La Tauromaquia, a special version has been compiled to accompany the exhibition.

The Wall Street 100 has been exhibited in Moscow, Prague and Spain. It will arrive in London in Spring 2010.

Cano on the bullfight

‘Since I was very small I always knew how to ‘torear de salón’. In other words, I understood the principles of what should be done in front of a bull, having practiced with my father. Even then I was attracted by the contrasts within the act, or ‘ceremony’. The bullfighter as feminine fact and the bull as masculine fact. Intelligence and instinct. Manipulation and natural condition. The colours of the sacred pageant set against bull black. And of course, life versus death.

The recording of this elaborate procedure would be a daunting task for any Spanish artist, each of whom will have been inspired by the same irresistible force while, in my case deciding to use only the most traditional of materials, pen and ink, with which to portray it. The bullfighting art, La Tauromaquia, is the most ‘plastic’ of all plastic arts. But the representations of it over the course of thousands of years have in general been the most formal.

Since Cretan and Roman times there have always been bulls and bullfighters willing to etch this relationship in the sand, and artists endeavouring to create a most expressive realisation of truth, or ‘faith’, if you like. In order to depict the bullfight, the artist must achieve a fine balance between technique and inspiration. One cannot draw without a degree of craftsmanship just as one cannot survive in the ring without technique, and one should never bullfight without the inherent element of art. The act of drawing is almost as reckless as that of bullfighting. Drawing is vanity itself, doomed to remain no more than a fraudulent mannerism if it does not manage to transport, transform and possess the personality of the one who draws. Just like the act of bullfighting’.