Susie Hamilton will be exhibiting a group of new paintings at St. Giles Cripplegate, London, a church that sits in the centre of the Barbican Centre. Having exhibited in the space before, in 2001, where Susie showed her ‘Mutilates’, it is apt that she has been asked to exhibit here again as part of the church’s commemorations of the 400th anniversaries of The Tempest and the King James Bible. The title, “A New Heaven and a New Earth” is taken from The Book of Revelation in order to bring both The Tempest and the King James Bible together and because the play, to some extent, dramatises renewal and joy emerging out of sorrow and disaster. As in Shakespeare’s other late plays, his tragicomic romances, the familiar world of wickedness and pain exists alongside possibilities of rebirth, visionary beauty and supernatural power.

The Tempest is also set in a kind of paradise–a new heaven and a new earth. The action takes place on a tropical or Mediterranean island which, through the “Art” of the magician Prospero and his spirit, Ariel, is charged with a dynamic energy that transforms, unites and vivifies. The island is alive with odd noises, unexpected mutations and sudden visions. Like Shakespeare’s metaphors themselves, these internal “artists” accomplish rapid wonders of metamorphosis, turning day to night, changing one thing into another, defying space and time and connecting the world of nature with a web of spiritual entities. The play in fact foregrounds the subject of art (Prospero’s and Shakespeare’s) and the way its miracles can be seen as either mere illusions or a way of connecting nature with the supernatural and revealing what lies “beyond the shadowy simulacra of mundane reality” (Philippa Berry, Hierophantic Shakespeare).

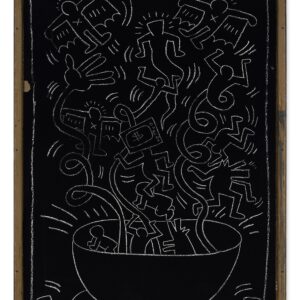

Susie writes, “I returned once again to the idea of the earthly paradise. As in my earlier work for Paradise Alone, based on the pastoral poetry of Marvell, the paintings are of a kind of idyll, though one that now extends to the bottom of the sea or the earth’s atmosphere. The paintings are all portrait in format since so much of the play’s imagery is of heights and depths and of movement between the two: from “cloud-capped towers” to “full fathom five”. And, in response to the visionary artifices of the play, these landscapes are deliberately artificial, magical realist. In them nature is altered, exaggerated and made strange. I depict a luminous, pristine, world with colour heightened, outline sharpened and dramatic contrasts in light and dark. As in much of my earlier work, I seek to transmit a sense of the uncanny and mysterious, through odd lighting effects or dramatic contrasts in scale or amorphous, humanoid figures distilled into shapes and silhouettes.”