“To use [the posters] for decorative purposes, to display them in bourgeois places of culture or to consider them as objects of aesthetic interest is to impair both their function and their effect.”

– Atelier Populaire Posters from the Revolution frontispiece, 1969

On the fiftieth anniversary of the revolutionary student protests that kicked off the Mai 68 Paris riots, this May Lazinc will present over fifty posters created and employed during the revolution.

This unique collection of posters was last exhibited at The Hayward Gallery in 2008 and now forms part of Lazinc’s permanent collection of counter culture and propaganda works. One of the largest collections of this nature, the Lazinc Propaganda Collection includes Chinese Maoist posters dating back to early 1900’s, Black Panther posters, Russian Communist Posters from the 1970’s & 80’s, Cuban Revolutionary posters as well as British counter-culture posters from the 1960’s – 1980’s. These iconic works have been cited as the forerunners of today’s street art movement, and have been an inspiration to many of the contemporary artists Lazinc has worked with, including Banksy, Vhils and JR.

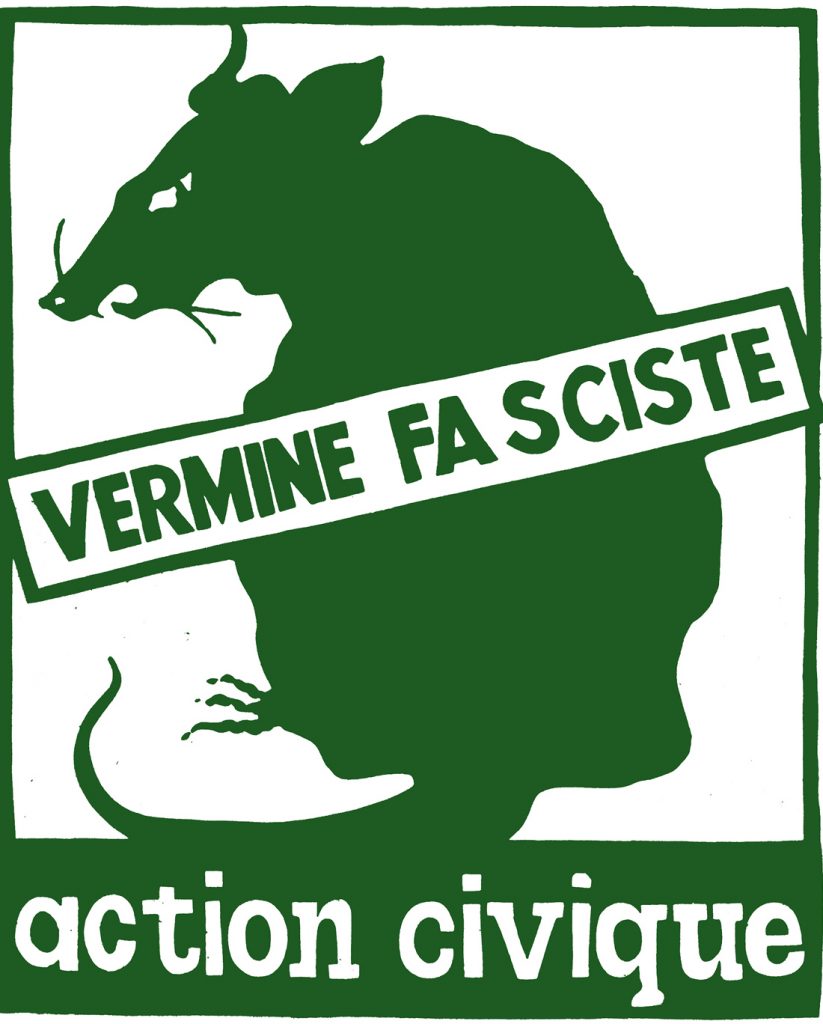

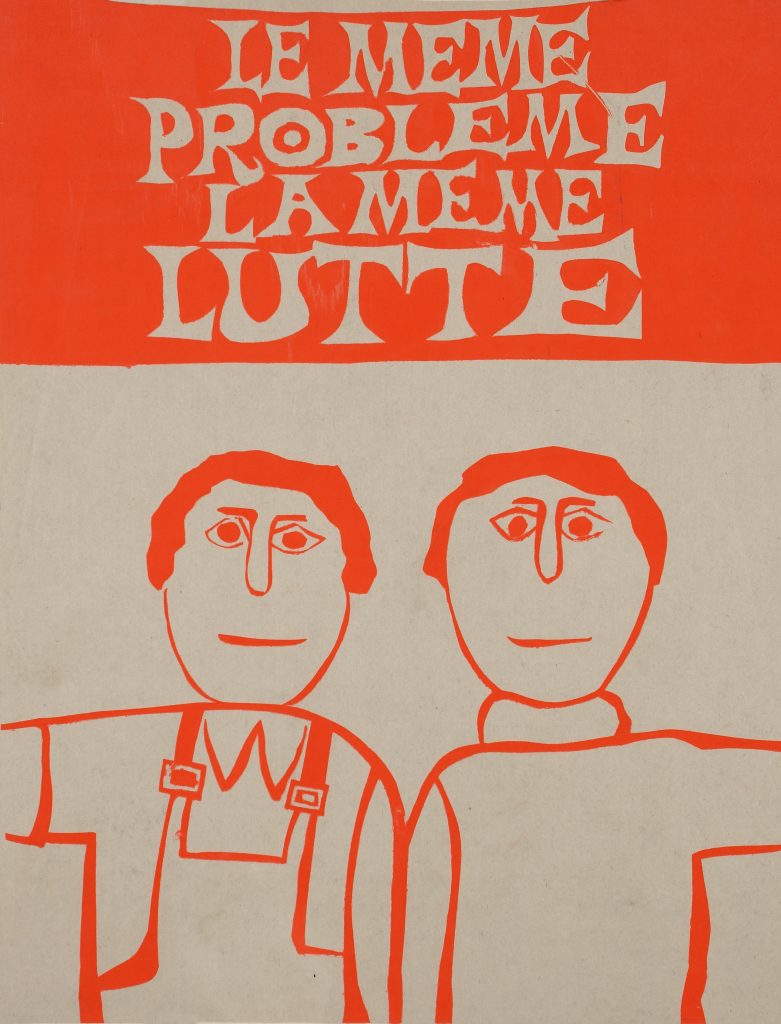

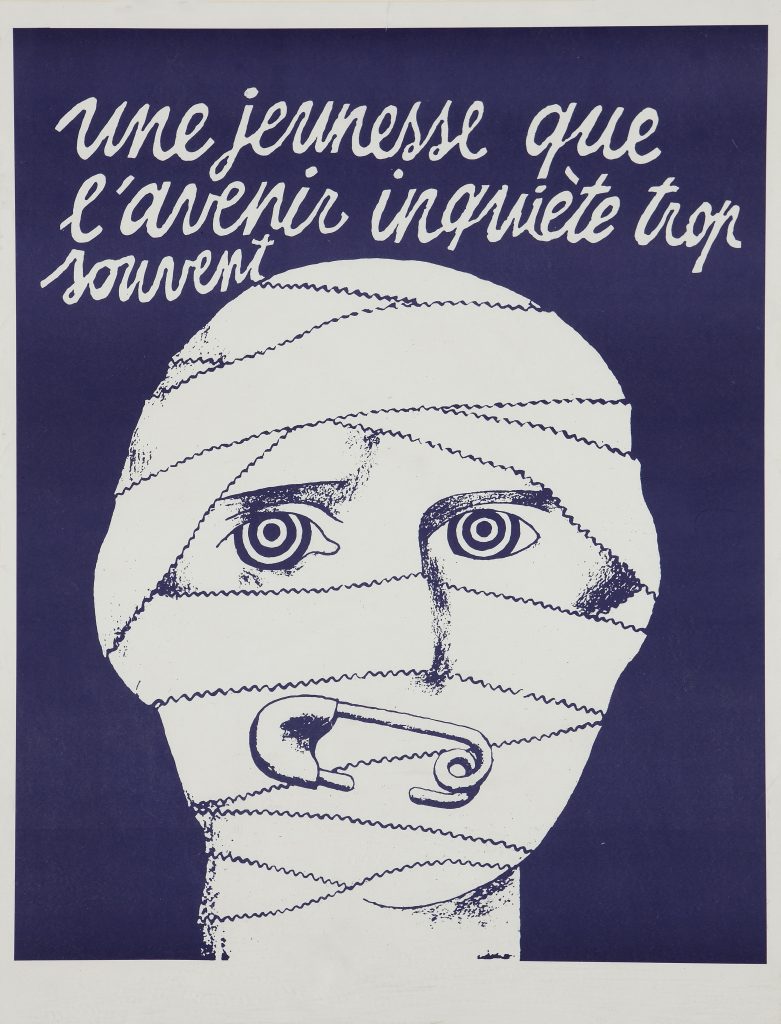

The works are original, screen-printed posters produced during May and June in 1968 and plastered over the walls of Paris. The posters became the visual symbols of the revolution and they depict solidarity between France’s students and workers; opposition to De Gaulle and parliament; and the denouncement of a fascist regime. The posters were created in the Atelier Populaire, the infamous workshop created in the occupied lithography studios of the École des Beaux Arts set up by artists and students. Screen-printing was used due to the opportunity of mass-production and none of the posters were signed by individual artists.

In a first for Lazinc, the exhibition will include ephemera from the period to contextualise the artworks in a historic setting, including archival photography, memorabilia and film footage captured during the riots. Mai 68, Posters from the Revolution, will start an important conversation around the fiftieth anniversary of the Mai 68 riots and the place of art within revolution. What effect did the Mai 68 posters have on art? What value do the posters have as pure art? And what is the place of posters and art in today’s protests?

The final room at Lazinc will be a replica of one of the Atelier Populaire studios, showing the make-shift

working spaces used to create the screen-prints. The installation will be left as if interrupted, posing the question of what the Mai 68 riots achieved and what is their contribution to art and history.

“The whole idea was that anyone and everyone could contribute to the content of the posters, students, fishermen, postmen, factory workers etc. There would be assemblies where the poster choice would be made. These would invairably be printed through the day and night and then pasted up on the night-time, for the city of Paris to see what the issues at hand were. This was a pretty risky business due to the heavy-handed tactics of the French riot squad. This is a classic example of the disposed and dis-enfranchised using the poster to give voice to their concerns. The fact that time has not diminished them or their sentiment is a testimony to their power.”

– Steve Lazarides, Co-Founder, Lazinc

Mai 68 Posters from the Revolution 4 May – 12 May 2018 Private view: 6-9pm Thursday 3 May

About Mai 68

The volatile period of civil unrest in France during May 1968 was punctuated by demonstrations and massive

general strikes as well as the occupation of universities and factories across France. At the height of its

fervour, it brought the entire economy of France to a virtual halt. The protests reached such a point that

political leaders feared civil war or revolution; the national government itself momentarily ceased to function after President Charles de Gaulle secretly fled France for a few hours. The protests spurred an artistic movement, with songs, imaginative graffiti, posters, and slogans. “May 68” had an impact on French society that resounded for decades afterward. It is considered to this day as a cultural, social and moral turning point in the history of the country. As Alain Geismar—one of the leaders of the time—later pointed out, the movement succeeded “as a social revolution, not as a political one.”