‘Buzz’, ‘Snap!’, ‘Rockit’, ‘Up all night’, ‘Cheeky, cheeky. Naughty, sneaky’, ‘Dance the dance, dancing feet’ – a few of the titles of artworks Rhys Coren has made over the last year. These titles are telling glimpses into this multidisciplinary artist’s creative practice that is inspired by 80’s electronic dance music, jazz and disco as well as his own experiences as a dancefloor habitué. Coren works across animation, writing, performance and painted marquetry, each medium flaunting its affinity with rhythm and the artist’s undying love affair with drawing. Form, colour and texture are integral to the strength of Coren’s painted, wall-based panels of interlocking board. The wall works may contain cartoon-like clouds broken up by grids of spray-painted colour and texture, overlaying the works with a cheeky sense of humour.

On the occasion of Coren’s first solo show at Seventeen (10th March – 15th April 2017), Marcelle Joseph talks to Coren about life as an artist in London.

You had a big break between your BA and your postgraduate studies at the RA Schools where you graduated in 2016. Now you’re grafting away alone in your studio in Elephant & Castle. What’s life like in the real world as a working artist after your cushy three-years in Mayfair at the RA?

It was quite a big break, yes. But I was always making art and always trying to contribute to whatever community I was part of. I worked collaboratively mostly, with different independent and artist-led initiatives, even curatorially at times. But I was always working. I needed that time, though, as I was a bit of a slow-starter.

Those years after my BA, first in Bristol then in London, juggling all manner of shitty jobs and debt as I also tried to educate myself further on art… contribute to whatever… and build myself a practice… were terrifying and financially very stressful. But they allowed me to appreciate more the things I already loved, and I began to make work about those things as a result… indulging my pleasures in music, animation, design and sub-culture. I also began to lean more on skills and techniques I enjoyed most, encouraging a DIY, self-sufficiency. This was a huge breakthrough for me.

Getting into the Royal Academy came soon after this breakthrough. This was seven years after completing my BA and I was 30 years old. I’d made the first body of work that I was truly proud of, and I’d managed it whilst living in London with next to no money and no formal structure whatsoever. All I could think about was how much more I could do with the support the RA offered. So, once there, I spent every day of those three years like it was my last. I lapped up everything I possibly could – everything about the school, the library, the student-run bar, the Royal Academy itself, the statue of Sir Joshua Reynolds, the postcode. It was amazing. It blew my mind, and it was one of the most amazing experiences of my life.

Despite this, leaving the RA was almost as exciting as getting in. That may sound surprising coming from someone who waxes lyrical about the place at every opportunity, but life there is about this intense introspection and analysis. Your week is heavily timetabled, and you have a responsibility to the rest of your year group to be present and engaging. That’s not always the most productive environment for outright making. That’s what I am ready for now. The Royal Academy defined who I was for a long time, but really it was just a phase, like the phase before. Now, this new phase is the Elephant and Castle phase… The Plaza Plaza phase. A phase I’m loving, working from a small, independent, artist-run studio with an exhibition space out front, tucked away off the New Kent Road. Glen Pudvine carrying on the great work of the now USA-based Jesse Wine, the artist who set it up in 2011.

I think it is important to dispel this myth that the RA or Mayfair is ‘cushy’ for everyone. As a student there, you are definitely one of the lucky few. But getting into the RA by no means ensures an easy time, either. It’s a total headfuck coming from a modest background and being surrounded by the most extreme wealth. Its location, for many, means long and overcrowded commutes and never before experienced problems getting materials. Some students really feel the pressure of the wider RA institution, and you are all different ages and at different stages in your development (though, weirdly, these were some of the things that drew me to it). But, one thing the RA can ensure is it will do everything it can to support you, and you will almost certainly be a better artist for going. How much better depends on you. The more you give it, the more it gives back.

As for the ‘real world’, even when I was doing the bare minimum of the shitty work required to pay rent, like painting a warehouse floor at 5am, or cleaning a nightclub wall at 4am, I felt lucky. To have a focus… to have the option to make and think about art… to avoid the ‘real’. I don’t think I’ve been in the real world since my first day of my Foundation Diploma at Plymouth College of Art in 2001.

Your wall-based works are feats of engineering genius with the most amazing textured colour. Could you explain your process and how music and drawing fit in?

I feel uncomfortable thinking of these things as genius. I would agree that the work has a strange eloquence once it is finished. Something I find ‘strange’ because I know about all the stages leading up to it hanging on a wall. They’re really quite modest and scrappy, even.

The process is one that, instead of trying to fight my odd, compulsive behaviour, completely embraces it through compartmentalising the picture making process. It makes a weakness a strength. To break everything down into stages, then to break the picture surface down into pieces; it’s a way of working that I find so much more productive, whilst also allowing me to care for every individual part of a picture. Every graphic component can be held in my hand, slowly textured and pigmented, allowing an intimacy with the work I hadn’t really felt before.

Music has been material, content, motivation and fuel for the work. By that, I mean that early works were about actual songs or memories experienced during specific music. Animated work often has music in it. And, even when the work is inspired by something entirely different, listening to music helps me work. Hoping that the rhythm of the music can creep into the imagery. Music has also been a handy metaphor for understanding how to make and relate to a picture, too. Thinking about tone, texture, harmony, rhythm, pitch.

I am just as much inspired by the written and spoken word, traveling around London, design and old animated films as I am music. It’s just that I listen to music, a very certain type of music, for most of the time I am in the studio. Occasionally, watching old films as I work, especially animated ones. But the music I listen to is music that has the power to cast a spell over your body and alter your mood. People who make dance music know they have made good dance music through the involuntary reactions the body makes. The same can be said for people who write comedy. Art doesn’t have anything quite so specific or exaggerated in terms of bodily response. It can be far slower burning, too. I guess I like the idea that a work can make you dance or smile before you yourself have even worked out if it interests you on a more conscious level.

Last year at the RA Schools, as part of an Open Studios evening, you presented a performance where two jazz musicians improvised an arrangement according to the rhythms of a two-screen animated video you made. Was that an important and pivotal work for you – mixing live music with your animated video work? Do you plan on continuing in this vein in the future?

Yes and yes. I actually staged that performance again with a saxophone player in the summer, and I am working on a new animated work to be scored by musicians. But, rather than it be one, continuous piece, it will be broken down into chapters with different music and musicians depending on the character of each chapter. I can see it taking a few years to do.

The musicians I worked with were Gary Crosby, Moses Boyd and Binker Golding of Tomorrow’s Warriors (amongst other projects), a huge youth jazz orchestra who are based at Southbank Centre. I sometimes stop for a wee there on the way home and had the luck to hear them one day. Working with them was one of the most inspiring and humbling experiences I’ve ever had. True magicians. Their dedication to their craft has taught me a lot.

In December 2016 at a solo show in Paris at galeriepcp, you presented a new animated video work alongside your wall-based works for the first time. At a studio visit, you mentioned to me how it was important for the two media to be presented in different spaces in the gallery. Can you talk about that and why the separation is important to you?

I can’t read a book when the TV is on or music is playing. I find that the imaginative space I enter to read is very similar to how I would look at a painting. So, by that logic, I find it hard to look at a painting whilst moving image or sound is playing close by. I feel that literal, real-time, durational work snaps me out of my own imagination. But, equally, the hypnotic, transformative qualities that moving image and sound have are something I feel very excited about. It is just that the real-time sort of bullies the imaginative. There may be room soon to deliberately butt the two together at some point, finding energy in the clash. Who knows? But, for now, I feel there is much more to gain from keeping one over here, and one over there.

How did you approach your first solo show at Seventeen entitled “Whistle Bump Super Strut”? Given that your wall-based work has a vibrating pulse of its own, is the curation of the works across the space important to you?

Very much so, but in a space this large… or ‘spaces’ plural, I should say… it is less about a rhythm created through the quick succession of works in a line or circumference. That’s something I have played with in the past, as each work is generally quite individual and a sequential reading can be interesting. But, the larger size and dividing wall at Seventeen allows each work to have a huge amount of space around it. So I have thought about the show in terms of connections between works in the two different rooms, each one sharing one or more characteristics from another work in the other room. It is like a puzzle in my head. A little like the surfaces of the individual works. It isn’t meant to be a puzzle that needs solving. It’s more of a gentle guide from my end, to help ease the work into an otherwise quite daunting space.

There’s a Dave Hickey idea that crops up in both Air Guitar and Pirates and Farmers, about how artists should ‘think in shows’. That really struck me. And, since leaving the RA, it is an idea that has really influenced my thinking. For both the recent galeriepcp show, and the Seventeen show, I made mock ups of the space, so that, at the very least, I had a subconscious blueprint guiding the individual works. This doesn’t cement the works in any sort of order, either, but creates a set of moves should something not work or need to be swapped over. There’s a balance I look for.

Your next outing is Frieze New York in May… As an artist whose work is presented to different global audiences, do you think about that when making the work? Can the history of a place where you are showing impact on the work (e.g., New York is where disco was born)?

Generally… no. I think that, whilst my practice is largely described as abstract, almost all the work is in some way rooted in something real; something inextricably British or perceived through the lens of Britishness. But, over years and years of reduction, I seem to be left with the essence of an image or sound – a sort of familiarity without being able to directly pinpoint the reference. For me, then, it is interesting to see how that is received abroad. Whether or not the work can translate. Maybe it is more accurate to say that I do think about it, but that the history of the place I am showing the work in doesn’t directly affect what I make, although I think I feel less inhibited because it isn’t in London, seen by my closest friends and mentors. I massively underestimated the effect of that pressure for Whistle Bump Super Strut. By the end, I’d lost all objectivity and developed both a Berocca addiction and nervous twitch in my left eyelid.

HOWEVER, New York is probably the one exception, as it is somewhere I think about a lot. I think it affects what I make anyway. Growing up, my favourite music was from there, my favourite artists were from there, and my favourite BMX and skate videos were all set there. I think NY is special like that, in that you can feel you know it without ever going there. So, when I finally got the chance to go in my mid-20s, instead of the Empire State or Statue of Liberty, I made little tourist trips to the sites of Warhol’s Factory, the Cedar Tavern, Brooklyn Banks, Studio 54, The Loft, Paradise Garage, CBGBs and the corner of 53rd and 3rd from The Ramones song. New York exceeded my wildest expectations, and I have been infatuated with it ever since.

We found out that we got into Frieze late last year, so I wouldn’t be surprised if that infatuation added a little optimism to the work for Whistle Bump. The summery feel of disco emanating from a wintery basement in London. Maybe, then, for Frieze New York, I need to take a slice of drizzly, grey London to even the score.

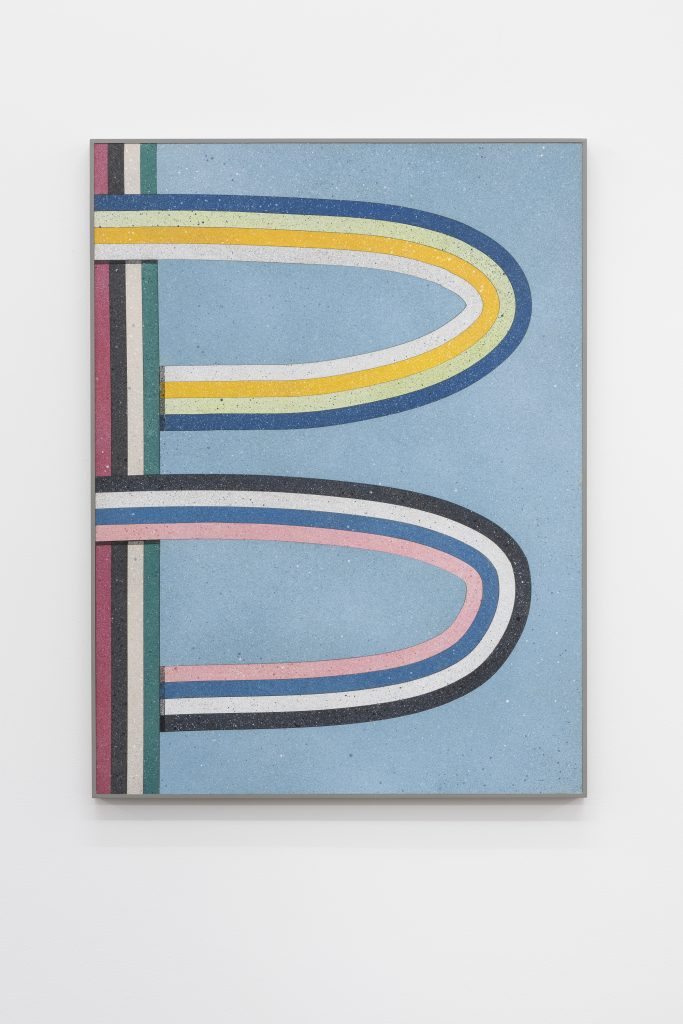

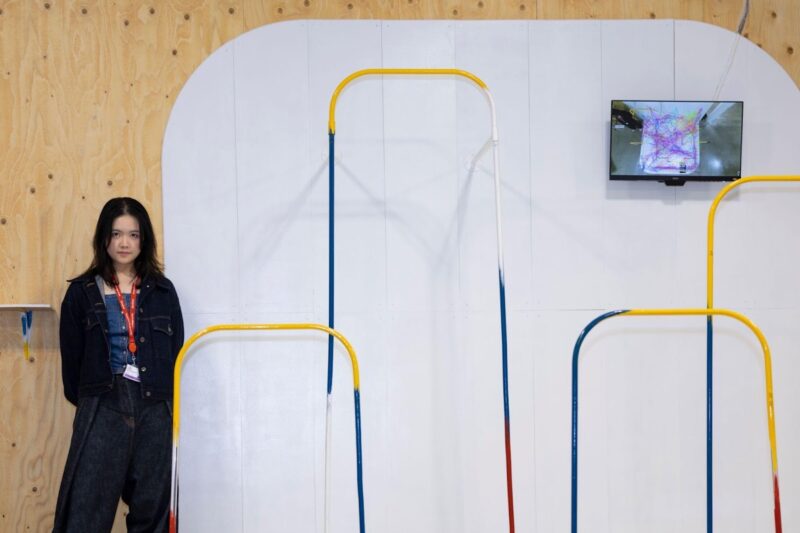

Captions

Individual works and installation views from Rhys Coren’s solo exhibition, Whistle Bump Super Strut, at Seventeen, London (10th March – 15th April 2017), courtesy of the artist and Seventeen, London, Photo: Damian Griffiths.

Links

About the Artist

Rhys Coren (b. 1983, Plymouth, UK) is a London-based artist who completed a Postgraduate Diploma at the Royal Academy Schools, London in 2016. Recent solo exhibitions include those at Seventeen, London (March 2017), galeriepcp, Paris (December 2016), Jerwood Project Space, London (2014), Horatio Jr., London (2014), and SPACE, London (2013). He recently curated the group exhibition Cuts, Shapes, Breaks and Scrapes at Seventeen, London alongside Gabriel Hartley and he has co-founded curatorial projects including Opening Times and bubblebyte.org. Selected recent group exhibitions include: Walled Gardens in an Insane Eden, Z2O Sara Zanin Gallery, Rome (2017); Beyond the Cartoon, Cassina Projects with ARTUNER, New York (2016); Royal Academy Schools Degree Show, Royal Academy of Arts, London (2016); Studio Leigh, London (2015); Drawing Biennial 2015, Drawing Room, London (2015); E-Vapor-8, Site Gallery, Sheffield, UK (2014); Symbolic Logic, Identity Gallery, Hong Kong (2014); Stop / Action, Test Space, Spike Island, Bristol, UK (2013); Young London, V22, London (2013); and Magic 8 Ball, FOLD, London (2013); The Response, The Sunday Painter, London (2012); Happy Accident, Wandering Around Wandering, New York (2012); VIDEO PROGETTO, Grand Union, Birmingham and 26CC, Rome, Italy (2010). Coren is represented by Seventeen in London and will present a solo booth for Seventeen at Frieze New York in May 2017 and a special screening at Kunstall Stavanger in Norway later this year.