So, where did you grow up?

I grew up in Florida, in a town called Jacksonville. It was a pretty happening place in 1900’s, with a vibrant music scene, progressive architecture, and majority of America’s silent film studios (causing a fair amount of chaos). It’s a quiet, buttoned-up conservative place now, but it has this vibrating stuff under the permafrost – you get a sense that there’s something else hibernating just under the surface. My brother and I grew up in a Craftsman style 1920s bungalow. My mom worked at a hospital and my dad was a salesman. Still, even in the 1980’s it was a great place to be a kid, there was lots of fun to be had, but of course you had to seek it out. The city did happen to be the home to a world class performing arts high school, which acted as a magnet to draw out all the creatives and other misfits from all the other schools all over town and put us together in one spot. I was incredibly lucky, in that because I liked to draw, I auditioned and was accepted. Everyone there was theoretically working toward honing the skill set in their field: creative writing, drama, dance, music, visual art, etc., so I still have know idea what a normal high school experience is really like. At mine, the basketball courts were torn down to enlarge the theatre – and no cheerleaders, but lots of ballerinas.

Has there been one person that has influenced the course of your life, or the course of your work?

That’s a tough one. The truest answer would be my grandmother. She was a unique kind of continental person who was nevertheless living her life in a very conventional American town. Her parents were German and French immigrants, and they couldn’t speak a common language when they first met. She seemed to me to be like a normal American grandmother, but her heart was also elsewhere. The whole world was hers. She was a housewife and yet had this other secret life – she also published poetry, was a civilian flight instructor during the war, worked as a document translator from her dinning room table, and just did all kinds of incredible stuff that I only found out about after she had died. She had lots of grandkids, and each time one of us turned 14, she’d let that one pick a place to go and she’d take you there. I chose London, and as a consequence instead of getting sunburned back home, I got to see museums, castles, and Cathedrals, and with her connections, hang out in the editing rooms and wander about through Pinewood studios.

Do you remember when you saw a painting that inspired you particularly?

Probably the first time that happened for me, was seeing Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Wedding at the National Gallery. When I saw it in the flesh, it was wild, because it’s such an intense image, but I never realised how tiny it really was. You understand, it’s hung in the furthest possible room from the Gallery’s entrance, and while I’m sure the picture gets plenty of foot traffic, when I was there, there was no one else around. I had the picture all to myself, in this wonderful very private moment. I was really young at the time and as I think about it now, it feels quite surreal.

The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, Jan van Eyck

Can you describe your artistic process?

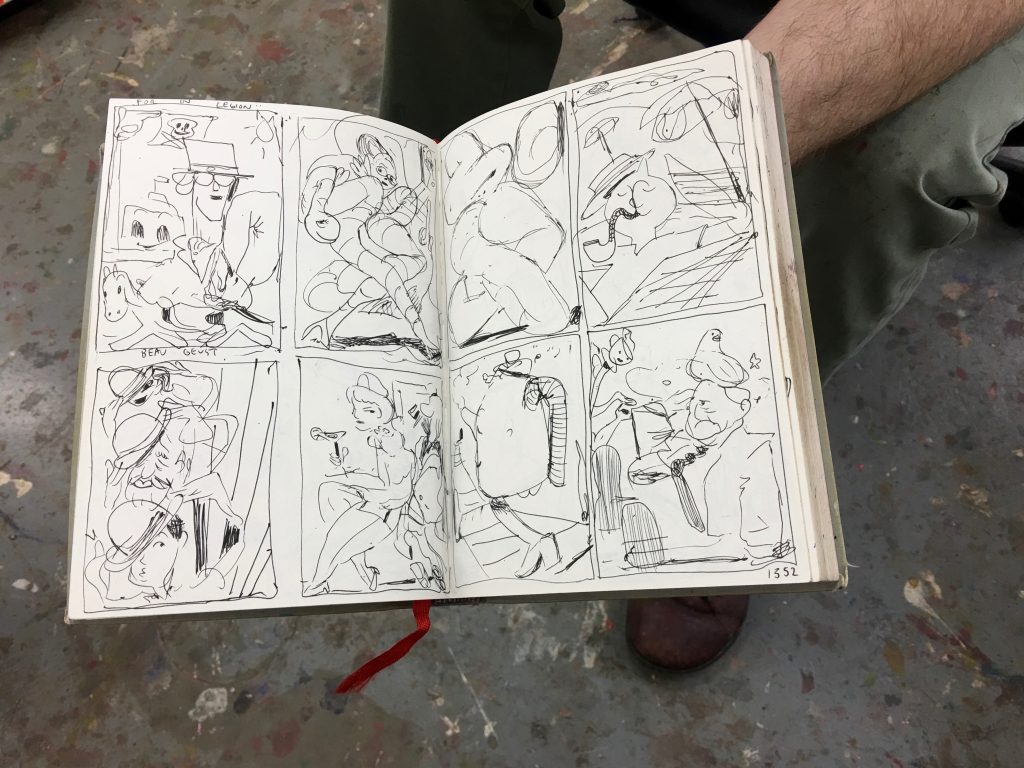

Well, It’s a mixture of planning and spontaneity. I tend to carry a little book around with me everywhere I go. I quarter the pages and scribble things down while I’m having dinner at a restaurant, or at the park, or on the tube, or just waiting around for any reason. Everything I do later is developed from the things that happen in the book. Content-wise, there’s a smattering of observational drawing, memories and bent nostalgia play a part too, but a big part of what makes the process work for me is that in the beginning, I don’t know everything about whats happening or why. Subconscious forms and interesting themes suggest themselves, and I try to I allow them to live on the page without any initial expectation of immediate understanding. Lots of sketches go nowhere, but as they’re all bound up together, it’s really easy to assess which ones have the potential to be developed further. And because the initial sketch is relatively crude, it makes no difference whether I’m doing a small ink drawing or a large oil painting, I’m still expecting that I’ll have to work out some of the unresolved elements from the reference sketch in mid-process (positive/negative space, anatomical irregularities, colour palette, etc). And that quality being present in the final work, of knowing the direction a painting should be going, but also improvising and making course corrections – that is the essential ingredient I attempt to hang onto when making a painting.

Jonathan Lux’s sketchbook. Photograph by Rosie Osborne.

Is there somewhere you go to seek inspiration?

Ideas happen organically and the world is full of influences. But if something really impacts my practice, It’s not because I sought it out – its a consequence of my being in the right place at the right time. Or maybe an idea has deconstructed itself through time, and I can understand what it could mean. Good things have happened to my practice as a consequence of travel, and I’ve been able to understand some things that were previously mysterious. If on the other hand the idea is a respite, besides the studio, I really like the cafe under the National Portrait Gallery. It’s small and it’s got nice brick arches and a glass ceiling so you can see the tourist’s feet – it’s kind of crypt-like in a way, but with wine and cheese…

Would you say your work was autobiographical?

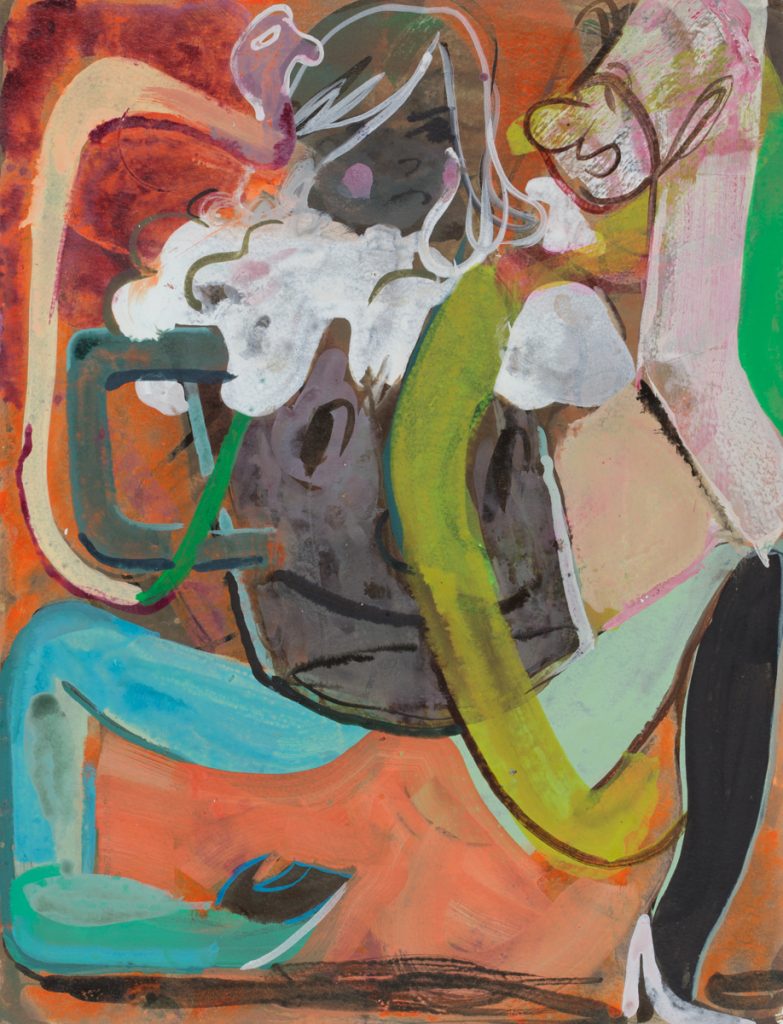

Oh yes, definitely. There are some thinly-veiled autobiographical things in the work, always, but the great thing is that no one ever sees them. I can connect with people I care about, people I miss, places, and things that I’m obsessed with. I can just put it all out there, and often, the references are embedded deep enough that they remain my secret. I have a thing I often draw which is meant to be a sudsy mug of american root beer, but most people read it as a pint. I love that!

Sarsaparilla Smile. Ink on Paper. Jonathan Lux. 2015.

Is there one work in particular that you’re particularly proud of?

There’s a recent painting that I’ve been thinking a lot about. There’s this notion of the ‘third hand’ – the idea that you do your own thing, but that somehow, when you see it, you don’t know how it got there. It’s as if someone came in and messed it all up and played around with it. I always take pictures of my work in progress, so that I can follow where I’ve been and where I’m going. If I realise that I went in the wrong direction, I can rewind a little bit, or reconnect with the early stages when things were very raw. This painting, The Rose, wasn’t exactly the result of the plan I initially sought to pursue, but the process of making it was so strange and exhausting, I wound up with something that was better, because it had it’s own weird logic. The more things I deleted, the better it became – I didn’t know what I wanted until I got it.

What inspired you to paint The Rose?

Well, in my 20’s, I used to love exploring abandoned buildings. One of those buildings was a famous shoe store, where this genius eccentric designer named Joseph LaRose who had a shop and eventually stored all of his excess inventory from his 50-year career. When he died, his estate was in limbo for a little bit. As our studio was across the street, and my friends and I figured out how to get into the building – we knew the that the building’s demolition was eminent. Inside it was filled with hundreds and hundreds pairs of eccentric women’s shoes, mostly from the 50s-70s. It was pretty fascinating. I’ve often tried to reconnect with that experience. The Rose was inspired this adventure and is about a girl falling inward during the experience of shopping for the right shoe.

Are there any materials that you’d like to experiment with in the future?

I struggle to be as good as I feel like I can with what I’ve got, so I’d rather just go on painting. I don’t really like taking vacations that much (my wife will tell you this is true!) and I usually have a fine time once I get there, but I am just very happy painting – I’m never bored. Charcoal or pastels aren’t really my thing. Ink is wet, so it’s sort of like paint, it misbehaves a lot, which I like. Ink runs, and reactivates earlier layers in ways both fascinating and alarming.

Jonathan Lux’s studio. Photograph by Rosie Osborne.

If you could have any painting on your wall from history, with no budget, which would you choose?

If I’m going to “borrow” something, that’s a tough choice. There’s definitely a list – Sickert’s portrait of Qwen Ffrangcon – Davies at the Tate, or Klimt’s painting of Mada Primavesi at the Met in New York. Today, my answer is that it would have be Max Beckmann’s Dream of Monte Carlo – gambling, sex, violence, mayhem – it’s pretty wild. With Beckman, he offers us so much, but that one is my favourite!

When do you feel most free?

That’s a hard one to answer. Being a Dad is pretty nice, because my children are just like sponges. They come out blank, more or less. And they give off a shocking generosity in their actions and interest in things. I don’t know how free I feel in comparison to them, because I have baggage and dogma which I’m constantly trying to discard. I like the studio and I like being able to make paintings because it’s probably the one part part of my life where I don’t have to answer to anybody else. I’m pretty passive at home with decisions like what we’re going to have for dinner, because I think I store it all up in a way for when I am in the studio. If someone were to come in and say ‘I don’t really like that purple’, I’d say, ‘well, the door’s over there.”

Jonathan Lux in his studio. Portrait by Rosie Osborne.

Jonathan Lux’s work will be exhibited at The World’s Mine Oyster, opening December 8th at 6pm – 133 Bethnal Green Road, London.