At first sight, the American abstract expressionist Agnes Martin, who died in 2004 aged 92, and the British painter of cats and mournful women, Gwen John (1876-1939), would seem to have little in common. But as I walked through the first major retrospective of Martin’s work at Tate Modern last week – in life, no such exhibition ever came her way for the deal-breaking reason that she would allow no gallery to produce a catalogue that included essays – it was John who kept floating unbidden into my mind. Un-mothered as children, in adulthood both artists suffered from precarious mental health, were periodically itinerant and, as they grew older, semi-reclusive.

Their mature practice, too, was similar, for all that Martin worked mostly in acrylic and John in oil and watercolour: repetitive, fixated with white, always chasing quietude. Most of all, both were (and are) easy to misread. Ascetic and outwardly fragile, this was not, by any means, the whole story. As Augustus John wrote of his sister: “She didn’t steal through life, but preserved a haughty independence which people mistook for humility.” The same is true of Martin, if only people would look beyond the cliches.

Although the Tate’s curators are careful not to make too much of Martin’s schizophrenia – in the 60s she was hospitalised repeatedly – they read her late work, for which their reverence is high, as an exercise in tranquillity, as if she were a nun and her paintings an extended meditation. In their notes they’re always beseeching you to look at the revealing wobble of her line, and when they quote from her copious writings it’s always the bits that sound most like an extract from some awful guide to mindfulness (“These prints express innocence of mind,” she noted of her 1973 screen prints, On a Clear Day. “If you can go with them and hold your mind as empty and tranquil as they are, and recognise your feelings at the same time, you will realise your full response to life.”) But then you turn to the paintings themselves, stubborn and sealed off. What steeliness. If they vibrate at all, it’s with determination, not serenity. They resist you with all the force of a concrete wall.

The Tate’s exhibition is broadly chronological, beginning with the work the artist produced in the early 50s, after her graduation from the University of New Mexico – Martin, who was born in Saskatchewan, Canada, was 30 before she knew she wanted to be an artist – and concluding with those paintings she made after her return there from New York. Her last work, Untitled (2004), a tiny drawing of a succulent in a pot, performs the role of full stop in a room crammed with other works on paper, a retrospective within a retrospective.

The early canvases – the curators insist on calling them “biomorphic” – are highly derivative, a series of cubist/surrealist/expressionist mash-ups that succeed only in as far as they make you think of other artists (Joan Miró, Mark Rothko, a touch of Graham Sutherland). But move on and something happens. In 1957 the dealer Betty Parsons saw Martin’s paintings in Taos and offered to represent her if she would move to New York.

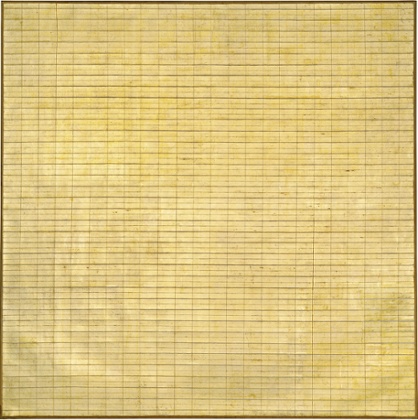

This Martin did, and it’s at this point, after she crossed the continent, that the show comes alive. At Coenties Slip in lower Manhattan, Martin’s neighbours included Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Rauschenberg and her close friend Barnett Newman, and the pieces she made in this period positively quiver with the camaraderie of her new life, with a sense of lost and found. Some feel excitingly contingent, her materials comprising beads, boat spikes and old nails. Others mark the beginning of her journey towards “the grid” of her middle period, when she outlawed curves from her life like false friends. Water (1958), a construction of wire and bottle caps, is a make-do-and-mend harp I longed to strum. Burning Tree (1961), an almost comically spiky wood and metal sculpture, resembles some loopy faux-medieval candelabra. Friendship (1963), a vast canvas of incised gold leaf and gesso, is a secular altar screen straight out of an old art deco hotel.

This is the most interesting section of the show and the most beautiful; there is a feeling of wild possibility, a sense that Martin can, and will, do anything. When you move on, all the heat seems to leave the galleries. In 1967, Martin sold her possessions, bought a pick-up truck and left New York in search of solitude.

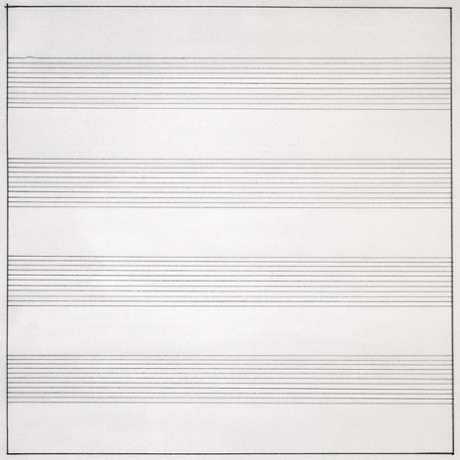

Having settled on a remote mesa outside Cuba, New Mexico, she didn’t begin painting again for five years, at which point the grids – think of the pages of an old-fashioned French cahier – are replaced by horizontal lines, and the darker tones by palest pink, blue and yellow. What’s striking about these canvases is the way they’re diminished by being in company with each other. A painting such as Untitled #17 (1980) – hazy stripes of varying widths whose fluttering boundaries are marked in graphite – might hold the interest in isolation: you could get lost in it, like fog. But set among its peers, it disappears. The Islands I-XII (1979) is a group of seven almost-white paintings – each one is marked with some barely discernible pencil lines – that Martin considered a single piece and which the curators deem to be among her “most silent works”. They say this as though it were high praise, but I experienced them as something muffled, frustration and boredom in fierce competition to hurry me from the room.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.