In 1981, using an Arts Council camera and 16mm film, Gilbert & George explored their idea of Britain. The hour-long home movie is one of many highlights of this inspired Hayward show. The film cuts between footage of their double act as living sculptures, deciding whether to “buy another vase”, to footage of flapping union jacks and marching soldiers (in the year before the Falklands war), to interviews with young East End men who stare fixedly at the camera and try to respond to the directive to “describe their lives so far”. Most of the interviewees don’t get much beyond “It’s been all right”. One, with a bit of a Paul Weller haircut, thinks for a while before reflecting: “Really, it’s been a total disaster. I’ve got in a lot of bother. Some of it has been a laugh though. And things have got better lately… It’s only recently I’ve been to Southend.”

That sentiment might make a succinct summary of the tone of History Is Now – seven artists’ discrete impressions of the nation in the three score years and 10 since the end of the second world war. In some ways the show is the ultimate Blue Peter time capsule, an attempt to curate the representative traces – from camouflage flak jackets to Farrow & Ball paint charts – that have formed and shaped us, got us where we are today. The artists – film-maker John Akomfrah (who selected the Gilbert & George movie among others), conceptualists Simon Fujiwara and Roger Hiorns, photographer Hannah Starkey, sculptor Richard Wentworth and sister act Jane and Louise Wilson – start from very different places. Still, the more you look, a kind of settled consensus about the themes of the past 70 years – of struggle and conflict, of the end of industry and the invention of consumerism – emerges. “We’ve got in a lot of bother… Some of it has been a laugh though.” That just about does it.

The timeline begins upstairs with Wentworth’s personal scrapbook of the scars of war itself (Wentworth, the oldest of the artists, was born in 1947). Robert Capa’s legendary photos of the D-Day landing at Omaha Beach (both ruined and rendered shakily timeless by a cack-handed darkroom assistant at Picture Post) are juxtaposed with one of Lowry’s Sunday afternoon paintings of Larkinesque “fools in old-style hats and coats” at the seaside in 1943. Beaches, Wentworth’s suggestion goes, would never be quite the same again. Tony Cragg’s adjacent mural, Britain Seen from the North, sees a country on its back, made up of the flotsam of the coming convenience age; broken records and plastic egg cups and bits of hub cap – the imported stuff the island nation has thrown away that keeps coming back on the tide, all washed up.

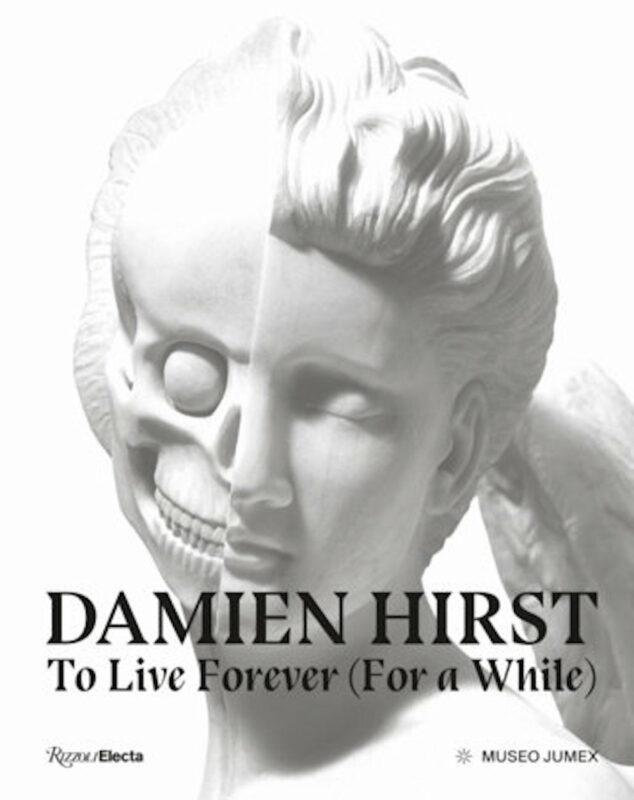

Chucked-out and covered-up fragments of recent history reappear throughout this show – as if from a mudlarks’ trove on the south bank of the Thames. Fujiwara, who grew up in St Ives in Cornwall, gathers some of the more resonant totems of the past two decades and houses them as if they were artefacts from a bronze age burial site in the British Museum. One of Meryl Streep’s outfits from her portrayal of Maggie Thatcher in The Iron Lady is showcased next to a half-tonne chunk of coal, exotic as moon rock, from a pit at Swadlincote, up the road from Orgreave. Sam Taylor-Wood’s still mesmerising film of the sleeping David Beckham shares equal billing with a stylised poster of Madeleine McCann’s telltale iris. Several other Young British Artists’ erstwhile greatest hits (Gavin Turk’s cast-bronze bin bag, a Damien Hirst spot painting) look suitably dated – Sensation has itself been set in formaldehyde. The soundtrack to Fujiwara’s collection is provided by a video of his own starring performance in a school production of Mary Poppins. Fujiwara was Mr Banks. The descant strains of Step in Time follow you round the exhibition.

Rather than attempt any kind of compendium, a couple of the curators – the Wilson sisters and Roger Hiorns – pull at single strands of social history and let the rest unravel. The Wilsons excavate the out-of-time solidarity of the Greenham Common protest and set it against the militarisation of public space first excused by IRA terrorism. The raw emotions of Greenham protesters’ diaries become emblematic of passions now seemingly as distant as those of Mrs Banks’s suffragettes. They are brought beautifully to life by juxtaposition with Penelope Slinger’s magical, semi-abstract film sequences, projecting her body as the battleground of art, and stiffly counterpointed by extendable yardsticks that once measured the precise span of hydrogen bomb chambers at Orford Ness; even the imperial measure is now obsolete.

Roger Hiorns’s room unpacks a very different archive; his obsessive-compulsive collating of documents relating to mad cow disease has the look of a serial killer’s bedroom wall – all drawing pins and newspaper clippings and conspiratorial government memos. There is film of John Gummer feeding his reluctant daughter a grim-looking burger, doomed to be played on a loop whenever his name is mentioned. Damien Hirst’s half-rotting cow’s heads have never looked so illustrative as here. You are reminded that the Sun rubbished the EU ban on British beef, and demonstrated its loyalty with page 3 “prime rump”; the Mirror, meanwhile, projected 500,000 deaths from Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. The truth lay somewhere – wildly – in between. There is a curious “analogue” quality to the spread of this archetypal scare story – all carbon-paper memos and typewritten folders. Virus stories had not yet become fully viral.

That same inflection, of defunct media, is one message of Hannah Starkey’s trawl through the Arts Council photo library of the period. The mostly black-and-white documentary photography – Chris Killip’s unforgettable Jarrow youth from 1976, Homer Sykes’s strange naked beauty pageant from Pinner fair of the same vintage – look like snapshots from another world entirely. Ezra Pound once observed that art “is news that stays news”. The converse also looks true here: art that is news quickly become history.

•History is Now is at the Hayward, London SE1 until 26 April

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.