Detail from Self Portrait (after Warhol) by Yinka Shonibare. Photograph: Courtesy Danjuma Collection/© Yinka Shonibare MBE. DACS 2014

There’s a body on the floor of the gallery, as if he’d been dragged up from an east Kent beach. Good lord, it’s Jeremy Millar. The exposed parts of his body are covered in weird holes. Something’s had a go at him. This ultra-realistic cast of the artist’s body in extremis is based on a story by chiller-writer Algernon Blackwood, and a hoax photograph by Hyppolyte Bayard, a 19th-century pioneer of photography who faked his own suicide.

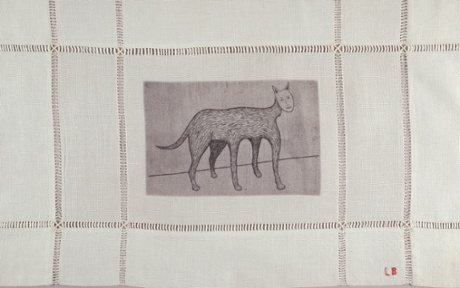

Millar’s surprising work comes with a lot of baggage. What self-portrait doesn’t? Some artists want to disguise themselves. Gillian Wearing got herself up as her own mother for a photograph, and Jo Spence wears a grotesque, grinning mask. Marjorie Watson Williams ran away to Paris in 1926, changed her name to Paule Véselay and went abstract. Louise Bourgeois drew and sculpted herself as a five-legged cat. You wouldn’t trust it as a pet. Nor would you want Isaac Fuller to eyeball you in a bar. His 1670 portrait has him as a magnificent monster, a pub-bore giving it large.

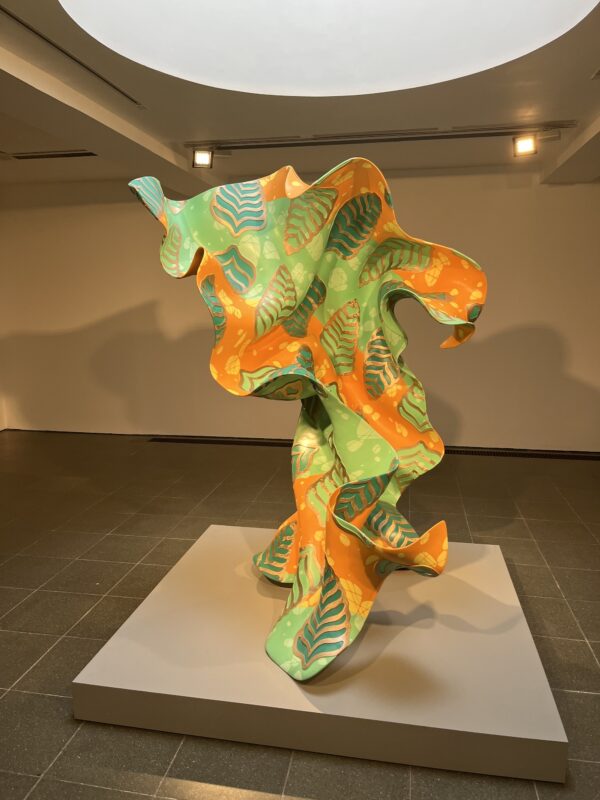

Self: Image and Identity at Turner Contemporary is an engrossing, sometimes alarming, baggy show of self-portraiture, from Anthony Van Dyck to now. You get all sorts here. There are lots of pasty men against brown backgrounds, holding things and pointing at things and giving us their eye. Even the bad stuff is often fun. As well as famous portraits, some are seeing the light of day after decades in the store-rooms of the National Portrait Gallery, and they now find themselves in the rum company of Gilbert & George (naked against a blown-up background of the things that float about in our urine), Tracey Emin’s film about why she never became a dancer (we are in Margate, after all), and a Damien Hirst cell-like vitrine, set up as a painter’s studio. You want to break in there and give Hirst’s imaginary artist a tutorial, or at least ask why he has lipsticked the words I Love You on his mirror.

Self-portraitists have to get over being in love with their self-image. Van Dyck’s last self-portrait from 1640-41, hung alone on a big brown wall, gives us a testy sideways look. Well he might. A successful campaign to purchase the painting for the nation raised £10m last year, and now the painting is beginning a two-year nationwide tour, which provides the occasion for this funny, sometimes affecting show.

Van Dyck’s portrait has a great balance of the formal and the intimate. Only the ornate gilded frame gives an indication of his public stature, as Charles I’s court painter. Artists care even less for baubles nowadays, but get themselves up in all sorts of self-regarding ways nonetheless. Sometimes, you can almost smell the vanity.

A photograph by Gavin Turk imagines what he’ll look like when he’s dead, and Graham Gussin extends a warning hand in front of his face, as if to say No Selfies Here. Yinka Shonibare sees himself as a portrait by Warhol. It looks like a bad-ass album cover.

For a year, Tehching Hsieh punched a clock, on the hour every hour, 24 hours a day, and each time a photograph was taken. The result is a jerky flickering film of an increasingly haggard man. Frank Auerbach’s charcoal self-image has a weirdly similarly juddering effect, in its accumulation of erased and redrawn, swerving marks. I covet Auerbach’s drawing, and Sir Francis Leggatt Chantrey’s little 1825 drawing of himself suffering from mumps. He holds his hands in an odd position over his groin, as if to signal that his balls had swelled as much as the glands in his neck.

In a darkened room, the recorded voice of Ian Breakwell describes what is like to be dying. “Every moment is a Proust moment,” he says at one point, as his greyed image fills the screen. My heart churns at this almost hour-long description of life with terminal cancer. Left unfinished at the time of Breakwell’s death, the artist left instructions for his colleagues to complete this candid, brave and heartbreaking work. Breakwell’s work stands up, among the centuries of the living and the dead.

• Self: Image and Identity is a Turner Contemporary, Margate, from 24 January to 10 May

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.