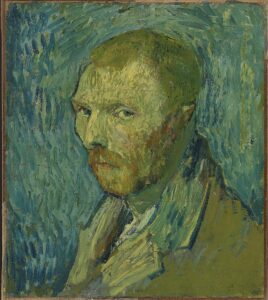

It is often said, quite casually, that a work of art is priceless. The discovery of a lost van Gogh painting in a Spanish bank vault demonstrates how this seemingly innocuous value judgement is an essential aspect of the relationship between culture and economics. For even in the week that Christie’s sold $725million of art in an evening, we are prudent to remind ourselves of the colossal power of culture in determining value.

To say that a work of art is priceless is to intertwine by sleight of hand the notions of cultural and economic value: by claiming that no monetary value can be attached to the work in view of its cultural importance, it affects an entirely arbitrary economic value in virtue of the fact that works of art – which are only artefacts – must, at least in principle, be exchangeable. As such, it is a value judgement that has a paradox at its heart because it makes a claim for value in two distinct senses where, in actuality, one of those senses is empty.

It is a quirk of art that this logic of combining a positive with a negative results in an absolute positive value. While cultural value is assured by the weight of art history, economic value must necessarily remain an unknown quantity until some specific circumstance requires a number to be conjured out of the ether. In this sense, there is a lightness to priceless works because they are emancipated from the burden that weighs so heavily on art: whether the work of an unknown artist struggling to sell a single piece or the manufactured wonders of megastar, art has exchange value built into its very being, which is so noisy that it interrupts the aesthetic experience itself.

Isabelle Graw thinks that all art is essentially priceless because it is impossible to measure the cultural, or symbolic, value. By this she means that the work of art has so many, varied resonances to the artist, the audience, the owner, the collector, the nation and history itself, that value cannot be measured. But, whilst this is the root of what we mean by pricelessness, I think it focuses too much on culture and contains two errors, one of over-specification and one of idealism. Firstly, art is not alone in possessing this kind of pricelessness, which is rightly accorded to all fruits of human endeavour; insofar as they are artefacts they will always mean something very profound – if entirely subjective – to someone or some people.

Secondly, idealism creeps in through the suggestion that the value of art is ideas and associations not inherent in the world of things but subsisting in the minds of human beings. Even if you reject the idea that artworks are commodities in any standard late capitalist sense, you have to admit that they are artefacts, and as such can be exchanged for currency, goods or services. Moreover, as artefacts, artworks come with the minimum cost of labour and materials which are relevant considerations in fixing a price for exchange. It is in virtue of at least this non-idealist conception that art can have an economic value at all. Even if we grant that it is essentially priceless on Graw’s fundamental definition of art as subjective cultural symbolism, we cannot simply deny the efficacy of economic value and the way it is built into the concept of art. Indeed, we need a more refined understanding of economic value in order to see just how powerful its cultural counterpart is.

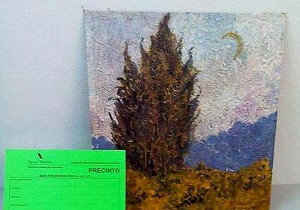

The reason we should hold on to the idea of cultural pricelessness while also allowing the standing possibility of an economic price is aptly demonstrated by the recent case of van Gogh’s Cypress, Sky and Country (1889). It had been missing for 40 years before it turned up in a safe deposit box in Madrid during a raid on tax offenders. But what had been missing is not a mere object; it is a piece of the art historical jigsaw, the loving labour of a Dutch master and a thing of beauty. We acknowledge that the work is culturally priceless precisely because its value in that respect cannot be measured, but almost as a cold ironic twist, its economic value – as yet undecided – is also demonstrated by the fact that it has been used as an instrument of tax evasion. Whatever happens to the painting now it will be subject to an economic value, even if that is a nominal or purely theoretical one, because its pricelessness has been co-opted by a scandal in which, somewhere along the line, a debt must be paid.

Here, then, we have the quintessential priceless work of art: an immeasurable cultural value which is positive in the extreme, set against a vacant economic value that could easily soar or never be realised. There is no price for this slice of art history, but as an artefact in the world of human commerce it is necessarily an object of exchange and as such has the possibility of an exchange value. It has, in effect, the highest value a work of art can have precisely because a price cannot be put upon it apart from some set of circumstances that force its sale on the market.

Insofar as economic value seems an intractable component of the work of art, we now have a fresh and ultimately more optimistic way of looking at it. While the cultural value of art is determined by all manner of subjective, ethereal factors, art is not inherently priceless because economic value is comprised of both the very real material value of an artefact and the arbitrary, swaggering price put upon it by the mere desire a market has for it. This should act as a veritable tonic to the art market’s wilful delusion that price is eternally justified by hubris, gossip and hysteria, since we commune with artworks, not just as commodities in line with all the others capitalism has to offer, but also as artefacts which are the results of human endeavour. As such, these artefacts have a curious combination of values inherent in them from the beginning, rather than only than only those wobbly, implausible values which are attached to them in the gallery or the saleroom.

This demonstrates that cultural value is king: the aesthetic, historical, emotional and experiential elements are the things in an artwork that we really hold in high esteem, which are the phenomenal results of its being a certain kind of artefact. Economic value always follows from this because it depends upon contingent factors that are constructed according to the operations of the market. Artworks are ordinarily cursed by this contingency, but priceless works trade on it as the omniscient guarantor of their status as such.

Words: Daniel Barnes