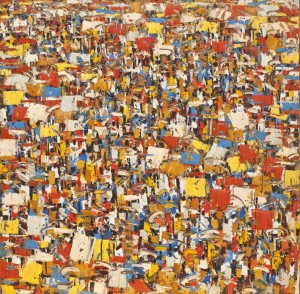

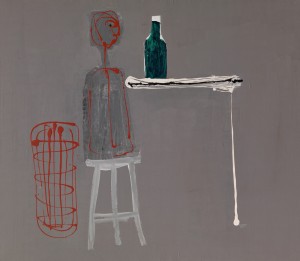

![nzebo_website[1]](https://fadmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/nzebo_website1-260x300.jpg) Boris Nzebo, ‘Etat des Lieux’, 2013, Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Jack Bell Gallery, London.

Boris Nzebo, ‘Etat des Lieux’, 2013, Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Jack Bell Gallery, London.

By Yvette Greslé

London’s first Contemporary African Art Fair dubbed 1:54 after Africa’s 54 countries presents a lively programme of exhibitors and events. Under the direction of Touria El Glaoui, 1:54 takes place in the West Wing of Somerset House, elements of which have been specially re-designed by David Adjaye. The fair’s artistic director Koyo Kouoh has put together an outstanding selection of critical conversations that includes curators and a number of artists (Zineb Sedira, Godfried Donkor, and Edson Chagas among the artists). Prominent figures in the field of contemporary art more generally, but with a particular relationship to the United Kingdom, are participating in these: Chris Dercon (Director of Tate Modern), Elvira Dyangani Ose (Curator International Art, Tate Modern), the phenomenon that is Hans Ulrich Obrist and Bisi Silva (Director, Center for Contemporary Art Lagos). Of course, there are many other significant critical figures and artists who continue to play an important role in contemporary African Art, and as with all public events the fair makes its selection.

Galleries located within the African continent, Europe, the United Kingdom and North America are represented. One of the strengths of 1:54 is its accommodation of different kinds of spaces: galleries and individuals who have played a pivotal role in developing the careers and practices of artists appear alongside Aria, the artist residency formed by Zineb Sedira in Algeria; and young galleries with a strong educational component such as First Floor Gallery, Harare. London galleries include the well-established October gallery, and the more recently formed Jack Bell Gallery and Tiwani Contemporary. While Tiwani Contemporary is not an exhibitor, its director Maria Varnava takes part in a panel on markets, economies and galleries. Galleries who have travelled to London from the African Continent include Galerie Cécile Fakhoury (Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire); Carpe Diem, (Ségou, Mali); and the Omenka Gallery (Lagos).

There is a great deal for the collector to contemplate at 1:54, and the programme of events provides a wider context for the experience of work. Artists represented range from those born in the 1980s (such as Aboudia) to artists born at the beginning of the twentieth century (Ernest Mancoba, 1904-2002). On display is ‘Fela Kuti’ (2010-2011), a work by Meschac Gaba, whose Museum of Contemporary African Art, curated by Kerryn Greenberg, was shown at Tate Modern through the summer (Greenberg is a curator of International Art at Tate Modern). Gaba’s ‘Fela Kuti’ is presented by In Situ, Paris (directed by Fabienne Leclerc). The fair’s emphasis is on painting, sculpture, mixed media, installation and photography; and gives some insight into how these practices have unfolded at different times and in different regions. Moving image practices and performance are not a presence, likely because they are perceived as less commercially viable. Although film screenings are incorporated into the events programme.

Koyo Kouoh, both the fair’s artistic director, and founder of the Raw Material Company, comments: ‘The market is important and we want all the galleries to do very well. We would like the fair to establish itself as an event in the artistic calendar of London. At the same time beyond the fair, it is important that people continue to engage with contemporary African art, and that is why the critical conversations are so important. These are a platform for debate and exchange. We hope that the fair will expand people’s knowledge of contemporary African art and also provide people with an axis. They may be people who are interested but do not know how to navigate the field’ www.rawmaterialcompany.org

1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair runs through to 20 October 2013 www.1-54.com The West Wing Gallery, Somerset House, Strand, WC2R 1LA.

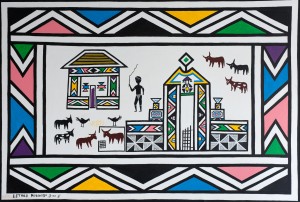

Images selected here focus on painting presenting a visual sense of how artists are working with a particular medium within African art. Painting practices incorporate expressive mark-making, and figurative painting. Artists deploy motifs, gestures, marks and materials in dialogue with many different kinds of histories and visual languages: these include visual images that are arguably transnational in character and images related to symbolism with local significance. Popular and street culture, including graffiti, is present in a number of works by a younger generation (Boris Nzebo and Aboudia, for instance). Artists engage materials that focus solely on more traditional media such as acrylics and oils or they incorporate found materials or substances. There is a political and social urgency to contemporary African art, as there is an interest in story-telling, heritage and the material substance of images, their processes, their construction and the experiences they produce. The dialogue is as much with Africa as it is with the experience of being human more generally.

Interviews:

Aboubakar Fofana, ‘Midnight in Santa Fe’, 2013, mud on linen textile. Courtesy Carpe Diem, Ségou, Mali.

Aboubakar Fofana, ‘Midnight in Santa Fe’, 2013, mud on linen textile. Courtesy Carpe Diem, Ségou, Mali.

Amadou Chab Touré: My gallery is there to help artists that I know. I teach at art schools in Mali (My PhD is in aesthetic philosophy). After my students leave school I observe them producing work but their work is not visible to anyone, no-one sees it. I try to show the work to bring awareness about art, and I am interested in helping artists to sell so that they can continue to practice. It’s about making things possible for the artist: getting people to see the work, and enabling artists to be able to function economically, and sustain their practice. I visit a lot of artists in many countries in Africa. When I visit them I don’t predetermine whether or not I will work with them. I am interested in artwork that moves me: it’s a communication between the artist’s work and me, not between the artist and me.

maisoncarpediemsegou@gmail.com

Ransome Stanley, ‘MASKE’, 2011, Oil on canvas. Courtesy ARTCO Gallery, Germany.

Ransome Stanley, ‘MASKE’, 2011, Oil on canvas. Courtesy ARTCO Gallery, Germany.

Joachim Melchers: My special interest is the art of African artists from the diaspora: artists who live in Europe or the United States and come from Africa. I am very interested in how the influences of different cultures come together in the work of artists who have this experience. If, for example, you look at the work of Owusu-Ankomah, he is inspired by Michelangelo on the one side and he is using traditional Adinkra symbols on the other. Ransome Stanley is half Nigerian and half German. He is putting African people and African symbols in his paintings but at the same time is influenced by European modern art. You can see it in the work of different African artists: the ways that these influences come together. It’s so interesting. I think London is one of the most important places for contemporary African art in Europe. I think more so than Paris and Brussels. We have some clients here in London and I am expecting to sell. This is the nature of a fair: it is a commercial event. The artist is expecting sales and we are too. We both have to survive, the artist and the dealer.

www.artco-art.com Wycliffe Mundopa ‘Not a Toy Not a Game’ (Part I), 2013, oil on re-enforced paper. Courtesy First Floor Gallery, Harare, Zimbabwe.

Wycliffe Mundopa ‘Not a Toy Not a Game’ (Part I), 2013, oil on re-enforced paper. Courtesy First Floor Gallery, Harare, Zimbabwe.

Marcus Gora: First Floor Gallery is the first independent contemporary art space in Zimbabwe. It’s an international, artist-run gallery, representing local and international artists. Artists have a hands-on relationship with the gallery, and work and develop their practice in dialogue with us. We provide educational opportunities, residencies and exchanges. We also provide them with a free space to exhibit their work without the pressures that do come with exhibiting as a young artist. In the Zimbabwean context pressures are political and funding-based. But we are trying to develop a space that is as free as possible where artists can develop their work, and launch their careers. We are also working to access the art market which is why we participate in art fairs. We hope with our approach, to make the gallery sustainable in the long-run, and to allow the artists to grow and develop.

Valerie Kabov: We are focusing on developing emerging artists in a very robust way. We want to enable artists not to be constrained by the pressures of the market, or ideological or political pressures. Our focus is on what is important to them in their lives. My background is as an educator and I focus a lot on the question of what happens when artists are given freedom. I’m interested in what happens when artists don’t have to make work that conforms to their idea of what might sell (or ideology, or someone else’s expectations). We’ve asked artists: ‘What would you do if you could do anything at all?’ All of a sudden this magic starts to emerge; and their practice develops in ways that are extraordinary. It’s been very inspiring.

www.firstfloorgalleryharare.com

Vincent Michéa, ‘Zone B’, 2013, Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Galerie Cécile Fakhoury, Abidjan.

Vincent Michéa, ‘Zone B’, 2013, Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Galerie Cécile Fakhoury, Abidjan.

Cécile Fakhoury: The point of the gallery is to be a contemporary art gallery in Africa. I work with many artists from the Ivory Coast because that is where I’m based but also with artists from Senegal, Burkina Faso, Ghana and so forth. But I also work with artists who are not from Africa. It is my intention to develop a contemporary art market from Abidjan with an art gallery that is international. I am interested in artists working in many different kinds of media. Here at the fair I have photography, painting, installation, sculpture, light boxes. I see a common point that runs across the work of all the artists, no matter where they come from in the world. They have a global way of expressing themselves. They’re talking about a global world. Identity is important, it’s who they are and it is present in their work. But they are also trying to reach something else, something bigger, perhaps something that is more global.

Ernest (Methuen) Mancoba, ‘Untitled’, ca 1985, oil on canvas. Courtesy Galerie Mikael Anderson, Copenhagen and Berlin.

Ernest (Methuen) Mancoba, ‘Untitled’, ca 1985, oil on canvas. Courtesy Galerie Mikael Anderson, Copenhagen and Berlin.

Mikael Anderson: We are based in Copenhagen and Berlin and we have had the gallery in Copenhagen for 25 years. I have been taking care of the estate of Ernest Mancoba who passed away in 2002. I worked with him, his wife the Danish artist Sonja Ferlov Mancoba and his son, Wonga Mancoba, who is here with me at the fair. We have known each other for 35 years. We did the first show in South Africa after the 1994 election because Ernest Mancoba and Sonja Ferlov could never go to South Africa because he was black and she was white. After the election we had an exhibition at the South African National Gallery in Cape Town and in Johannesburg. I don’t work solely with African artists. I do, however, work with some young South African artists including Moshekwa Langa who we have shown in Berlin. We have a relationship with South Africa.

![00706 copy[1]](https://fadmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/00706-copy1-300x147.jpg) Aboudia, ‘Untitled’, 2013, Acrylic & mixed media on canvas. Courtesy Jack Bell Gallery, London.

Aboudia, ‘Untitled’, 2013, Acrylic & mixed media on canvas. Courtesy Jack Bell Gallery, London.

Jack Bell: We started the gallery in February 2010. I had previously worked for another dealer. At that stage, I had been doing a lot of art fairs in the United States and in Europe. It seemed as though there was always the same cross-section of artists: very much focused on London, Paris, New York, and Berlin. I set out to shift this. When we had the first gallery space in Victoria I looked at the South Pacific, Haiti, Bangladesh, Mali, places like Benin. As I started to work on the African contemporary art shows I noticed that these really struck a chord with audiences in London. There is very dynamic work coming out of a young generation of artists in Africa. There’s also a younger generation of artists in Sub-Saharan Africa making work about where they’re from. This work is attached to tradition but at the same time it’s very edgy and contemporary. A lot of the countries I visited were just emerging from civil war and political and social instability. The artists have a lot to say and they are very good at executing high quality work. As the artists are emerging they’re very accessible for us to present in London. It really took off, we got some great press, and have attracted a lot of heavy-weight collectors. We’ve been trying to create a platform for the artists we work with in London, and launch them into the contemporary art world, outside of the ethnographic frame.

Amadou Sanogo, ‘Baiser le diable’, 2010, Acrylic on canvas. Copyright Amadou Sanogo. Courtesy MAGNIN-A, Paris.

Amadou Sanogo, ‘Baiser le diable’, 2010, Acrylic on canvas. Copyright Amadou Sanogo. Courtesy MAGNIN-A, Paris.

André Magnin: I started to travel around Africa in 1986. In 1989 I co-curated, with Jean-Hubert Martin, ‘Magiciens de la Terre’, at the Pompidou Centre and the Grande Halle de la Villette. For the first time, in a major exhibition, half the artists were from Europe and America and the other half from other parts of the world. I spent three years researching art in the African continent. After ‘Magiciens’ I met this guy who asked me to put together a collection of African art for him: this man is Jean Pigozzi. I became the Director of the Pigozzi Collection for 20 years and built a huge collection based on African contemporary art with artists who are living in Africa. We also curated many exhibitions in museums around the world. Three years ago at the Basel Art Fair Pigozzi tells me: ‘But none of our artists are at the fair, on the market’. I tell him: ‘But you bought everything, 12 000 pieces (laughs)’. I said to him that I will work towards creating a market. I opened my gallery in 2009 with artists I discovered during the course of 25 years. We have published books and have had many exhibitions. Amadou Sanago is from Bamako, Mali. He is very young: I discovered him a year ago. He has a good sense of colour and space. You don’t know if it’s abstract or not, it’s a mix of traditional and modernity. I like that ambiguity, and his work is very beautiful.

Soly Cissé, ‘Untitled’, 2013, Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy M.I.A Gallery, Seattle.

Soly Cissé, ‘Untitled’, 2013, Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy M.I.A Gallery, Seattle.

Mariane Ibrahim-Lenhardt: The gallery explores artists from around the world, with some focus on Africa, and contemporary African art. We juxtapose different practices from different countries and also emerging and established artists. I believe that young and established artists can show together. Anything that is to do with an unseen culture or subculture excites me, even though it addresses a limited audience. I try not to respond to mainstream ideas about Africa. Africa is not a country: it is a continent. I represent a tiny section of African art practice. Africa has been a victim of other people’s perceptions; and artists grounded in the continent have a sense of their own agency and play a critical role in shifting these. Perhaps there will come a time when we refer to artists as contemporary artists as opposed to African contemporary artists. It’s also very important for artists to develop their careers. They need platforms through which they can sell their work, and sustain themselves and their careers. I am very proud that many of my artists are actually based in Africa and collaborate with me in America. If collectors are interested in certain work we make it available for them on the market. The market enables visibility. Art galleries are also growing in Africa, and we are very happy to be partnering with a gallery in South Africa: this is the Rooke + Van Wyk gallery. Any collaboration is very beneficial and there are more opportunities now to work with African artists.

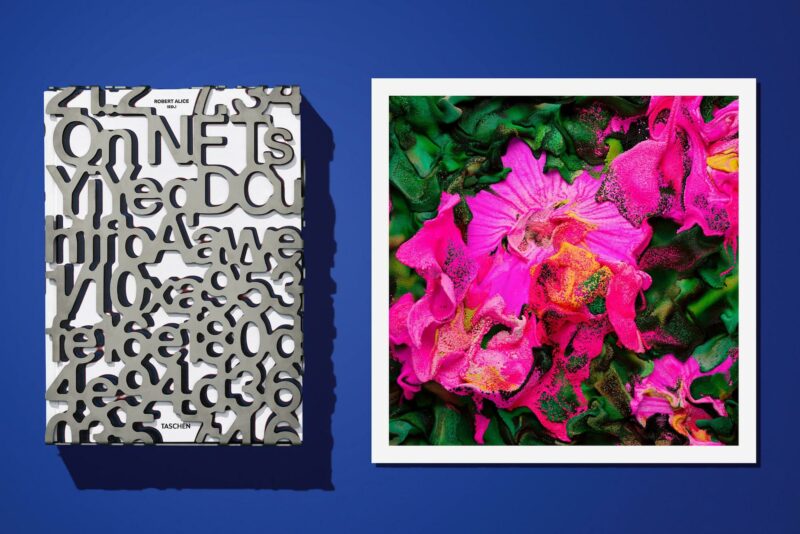

Esther Mahlangu, ‘Gateway’, 2005, Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, Equatorial Guinea.

Esther Mahlangu, ‘Gateway’, 2005, Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, Equatorial Guinea.

Marc Stanes: Esther Mahlangu is a very famous South African Ndebele artist. She is a traditional artist working with the Ndebele geometrical shapes historically used to decorate homes. She began working on canvas about 20 years ago where, using acrylics, she incorporates the Ndebele colours and shapes. She has exhibited all over the world, at the Pompidou Centre and so on. She is now in her 70s and so one of the older artists at the fair. She is incredibly humble living in the same village that she was born in. She’s not remotely interested in money for the sake of it. She sells her work and has dealers who sell her work but she puts money into her community. The Museum in Equatorial Guinea is currently under construction, in Malabo. The country has had a very complicated history politically. It’s a former Spanish colony among other things and it has had a troubled past. But economically it is now a powerhouse. Economics have changed things and people are now interested in their heritage and culture. But there need to be institutions on the ground to develop a new generation of younger artists. We receive corporate funding and so have the opportunity to put something back in. We buy from across the continent. My overriding remit is to put together a collection that will be a resource for future generations. We pick some well-known names. We pick young names. Hopefully these are artists who have a future and a story to tell. We’re here to educate and to excite vision.

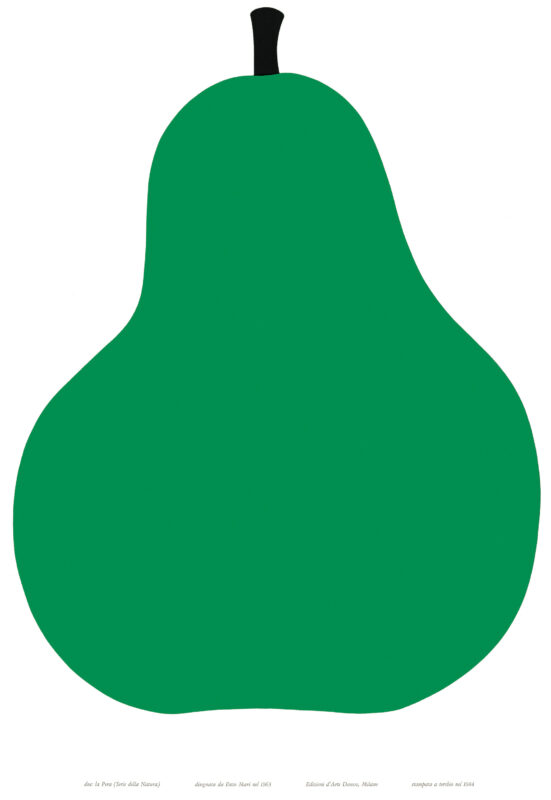

Ablade Glover, ‘Market Lane’, 2009, oil on canvas. Courtesy October Gallery, London. Photo credit Jonathan Greet.

Ablade Glover, ‘Market Lane’, 2009, oil on canvas. Courtesy October Gallery, London. Photo credit Jonathan Greet.

Elisabeth Lalouschek: We opened in 1979, and since then have showed contemporary artists from around the world. We called the work ‘transvangarde’ at the time. Our aim is to give a platform to international artists here in London. We first showed Ablade Glover in 1982. He has been one of our longest standing artists, and we will be exhibiting him again next summer because he is celebrating his 80th birthday. He loves impasto paint, and likes to squeeze out the paint almost directly from the tube at times and put it on with his palette knife. He likes, in his painting, to express things like the bustle and excitement of the markets in Ghana. He has an established, long-standing career; and is also one of the founding members of one of the biggest galleries in Accra, Ghana. He began showing younger artists there. The fair is an opportunity for some of the younger artists who have not had the possibility of being exposed in London to exhibit. It’s also an opportunity for galleries who have not had exposure in London.

1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair runs through to 20 October 2013 www.1-54.com The West Wing Gallery, Somerset House, Strand, WC2R 1LA.

Amadou Sanogo, ‘Qui Suis-je?’, 2013, Acrylic on canvas. Copyright Amadou Sanogo. Courtesy MAGNIN-A, Paris.

Amadou Sanogo, ‘Qui Suis-je?’, 2013, Acrylic on canvas. Copyright Amadou Sanogo. Courtesy MAGNIN-A, Paris.

Categories

Tags

- 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair

- African art

- Bisi Silva

- Chris Dercon

- Contemporary African Art

- David Adjaye

- Edson Chagas

- Elvira Dyangani Ose

- First Floor Gallery

- Galerie Cécile Fakhoury

- Godfried Donkor

- Hans Ulrich Obrist

- Jack Bell Gallery

- Kerry Greenberg

- Koyo Kouoh

- Museum of Contemporary African Art

- Omenka Gallery

- Painting

- Tiwani Contemporary

- Touria El Glaoui

- Zineb Sedira