Damien Hirst The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living 1991 Glass, painted steel, silicone, monofilament, shark and formaldehyde solution Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates ? Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2012

Damien Hirst Pharmacy 1992 Glass, faced particleboard, painted MDF, beech, ramin, wooden dowels, aluminium, pharmaceutical packaging, desks, office chairs, foot stools, apothecary bottles, coloured water, insect-o-cutor, medical text books, stationary, bowls, resin, honey and honey Dimensions variable Tate Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates ? Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2012

Damien Hirst Pharmacy 1992 Glass, faced particleboard, painted MDF, beech, ramin, wooden dowels, aluminium, pharmaceutical packaging, desks, office chairs, foot stools, apothecary bottles, coloured water, insect-o-cutor, medical text books, stationary, bowls, resin, honey and honey

Dimensions variable Tate Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates ? Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2012

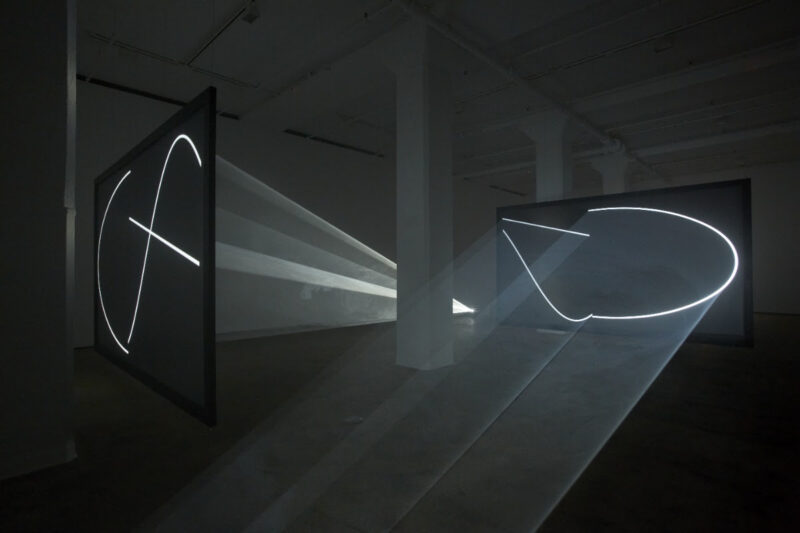

Damien Hirst In and Out of Love (White Paintings and Live Butterflies) – installation view 1991 Primer on canvas with pupae, steel, potted flowers, live butterflies, Formica, MDF, bowls, sugar-water solution, fruit, radiators, heaters, cool misters, air vents, lights, thermometers and humidistats Dimensions variable Private Collection, courtesy White Cube

Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates ? Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2012

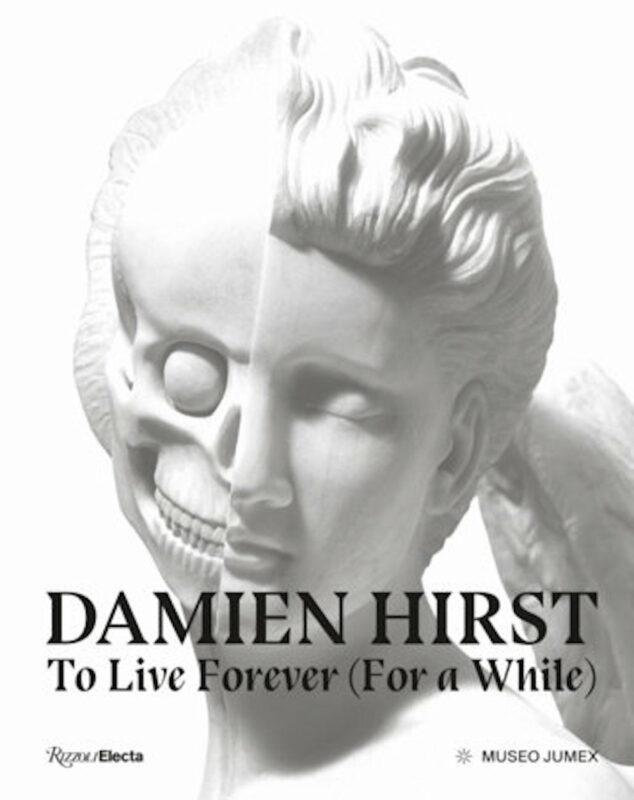

Damien Hirst (4 April – 9 September 2012) Tate Modern

Damien Hirst’s first major UK retrospective at Tate Modern reads like a greatest hits album of the artist’s 25 year career; the menacing shark in formaldehyde, the shocking bisected cow, the ubiquitous spots and psychedelic spin paintings. This quarter century survey features rarely seen early work such as the first Spot Painting from 1986, and charts the development of recurring iconography.

The Spot paintings are a familiar motif in Hirst’s work, although from an output of roughly 1400 spot paintings, he only painted around 20 before handing the job onto a team of assistants. This use of assistants was famously criticized by David Hockney recently, who declared in the posters for his Royal Academy Blockbuster show, that he created all his own paintings. Although Hirst isn’t the first artist in history to employ a team of technicians to visualize their ideas, think of a Renaissance studio or Warhol’s Factory.

In the same room as the original spot painting is Boxes (1988), a minimalist influenced piece from the seminal exhibition Freeze in 1988, which was curated by Goldsmith’s graduate Hirst, catching the attention and opening the wallet of Uber-collector Charles Saatchi. Of the exhibition Hirst has said: ‘I thought I was crap and all my friends were great’, however fast forward 24 years, and his name is far more recognizable than that of his contemporaries Sarah Lucas, Mat Colishaw and the late Angus Fairhurst.

A macabre monochrome photograph of a 16-year old Damien visiting a Leeds anatomy museum, and posing with a severed head, signals the beginning of a lifelong fascination with death. This interest in mortality is exemplified in a seminal work in the next room, A Thousand Years (1990), a glass vitrine containing maggots feeding on a cow’s head before hatching into flies, playing out the life cycle in an art gallery. After the death-obsessed Hirst picked up a chainsaw and cut a cow in half, the student who only managed an E in A Level art won The Turner Prize in 1995. Hirst’s fear of death is represented by the terrifying shark in formaldehyde, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) is perhaps his most iconic work, and instills an almost primal fear in the heart of the viewer.

The more squeamish gallery goer might prefer the installation In and Out of Love (1991), a far more uplifting experience created by placing fruit bowls on a table in the middle of a room full of exotic butterflies, which render the butterflies drunk by end of day. Hirst bred the butterflies for the original work himself at home to save money, and this is the first time its been exhibited in its entirety since.

Pharmacy (1992), a room lined with medicine cabinets containing boxes of familiar medicines, could also be said to examine the theme of death, in the sense that by taking pharmaceuticals we are attempting to postpone the inevitable. However, it has to be pointed out that Pharmacy is a recreation of Hirst’s Notting Hill restaurant venture of the same name, an essential stop on anyone who was anyone on the London party scene of the 90’s. It is claimed that when Pharmacy went into liquidation in 2003, Hirst’s savvy business manager Frank Dunphy, bought up all the fixtures and fittings that Hirst had designed, and these ended up in the Sotheby’s sale room in 2008, when the artist raked in an eye-watering £111 million in the middle of the economic downturn, a record for a living artist. Money and art have never been so closely entwined in the practice of an artist, and Hirst seems to have taken on the prophetic words of Andy Warhol, who said: “Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.”

This exhibition charts the development of Hirst from cheeky Goldsmith’s graduate to the richest living artist in the world, whose spot and spin paintings rake in the cash. Although one could argue that his incredible success is down to clever spin doctoring. Surveying his work from the last quarter century, it doesn’t possess the visceral quality of a Freud, or punch you in the guts like a Bacon, an artist who Hirst openly admires and who had a similar obsession with mortality, yet this exhibition proves that Hirst has created some of the most iconic artworks of contemporary folklore which undoubtedly pack a punch, and cemented his place in art history.

For the Love of God, Hirst’s diamond encrusted skull, is housed in a specially constructed viewing room in the Turbine Hall. Reputedly sold for £50 million to a ‘business consortium’, the life-size platinum cast of an 18th Century human skull is covered in 8,601 diamonds, and almost as valuable as The Crown Jewels. Indeed trying to get near them was almost as difficult, with a wall of Tate invigilators blocking entry because the press view was over, and the installation party to a private function.

Damien Hirst has his detractors who dismiss him as a one trick pony, nevertheless it is undeniable that he is adept at capturing the zeitgeist in his art, and playing on universal obsessions such as mortality and money to create vital, relevant installations that leave an impression, be it positive or negative, long after you leave the gallery. He sums it up perfectly himself: ‘Love it or hate it, it doesn’t matter as long as you can’t get it out of your head’ said Hirst

The exhibition runs until 9 September 2012, and forms part of the London 2012 festival, the culmination of the Cultural Olympiad.